By Michael Wright

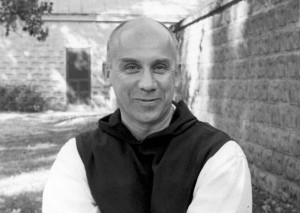

I first learned about Thomas Merton when I skipped chapel at my Christian high school. I started to meet weekly with a kindhearted Bible teacher who looked through my cynicism and saw a desire for a deeper spiritual life. I’m grateful for those conversations—especially the day he told me about a book written by Merton called No Man Is An Island. As I started reading it, I was excited to find a monastic writer with piercing insights into my own inner life and a Christian mystical tradition markedly different from the subculture around me. It was providential timing: I was slipping into depression that would last for years, and Merton quickly became a friend and guide through a spiritual wilderness. So today, in honor of his birthday and his lasting impact on the wayfarers and mystics among us, here are seven reasons why evangelicals should read Thomas Merton:

(1) Merton can introduce you to the larger Body of Christ.

A sola scriptura ecclesiology easily leads to an iconoclastic view of history. Or to say it another way, if you skip over two thousand years and use Acts as a blueprint to recreate a pure church, your cloud of witnesses will be on the small side. That’s the tradition I grew up with, and it left many people feeling untethered. Reading Merton introduced me to saints and philosophers, medieval mystics, the desert fathers, and many other men and women who are now a sustaining spiritual heritage.

(2) His writing integrates spirituality with psychological wisdom.

As a teenager in high school, I remember reading “I must decrease; he must increase” as a life motto. Misunderstanding this text contributed to a distorted sense of self-worth; this wasn’t a time for somber self-denial—it was a time to learn what it means to relate, to have adventures, to grow into my own beating heart. As a contemplative, Merton knows the inner life, and he writes about spiritual transformation in a way that can keep us from pursuing the right thing in the wrong way.

(3) He doesn’t sacrifice beautiful language to write faithfully.

Much contemporary evangelical writing (and blogging) relies too heavily on “Christianese” and vague truisms. Merton has the mind of a philosopher, the heart of a mystic, and the voice of a poet. His writing is engaging and precise, and he uses imagery and artful language that people from any background can appreciate.

(4) He makes room for darkness and doubt.

At the end of my first quarter at Fuller I was in a tumultuous crisis of faith; depression and theology mixed in unhealthy ways. Many of Merton’s prayers became my own during this time, and I could hold onto to God’s hand even as I doubted its reality.

(5) His writing is intelligent, but he puts rationality in its place.

A life of faith is more than the mind only, and God can be approached in many ways. Merton interacts deftly with both theology and philosophy, but his ultimate goal is to always push his readers towards prayer and sustainable spiritual practices.

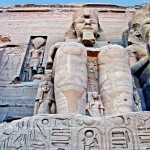

(6) His interest in Buddhism shows us effective interfaith dialogue.

Towards the end of his life, Merton was noticing strong parallels between his own Catholic spiritual practices and Zen. Rather than run from them, he entered more deeply into conversation, attending conferences, befriending Zen monks, and writing on the topic. This is not a hazy pluralism—he maintains the particularities of his Christian faith even as he explores the similar monastic practices of the Other.

(7) He makes contemplative life seem not only possible but necessary.

More than anything, Merton shows us that being a contemplative is not an escape from the world—it is a choice to enter one’s heart and life deeply, to engage culture even while resisting it with an active practice of prayer.

In this whirling modern world, I’m grateful for Merton’s words. If you’re interested, start with Thoughts in Solitude or New Seeds of Contemplation. Whether you read him or not, know that the life of prayer he wrote about is available to us at all times—whether God feels close or decidedly absent. And on a day like today, let us pray for that Trappist monk, and all who pray with him:

“My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think that I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road though I may know nothing about it. Therefore will I trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.”

-Thomas Merton

Michael Wright has a Masters in Theology and the Arts from Fuller Seminary where he manages social media and writes for FULLER Magazine. He is an advocate for artists incorporating their faith in their work and for churches trying to understand how to approach the arts. Find more at The Commonplace Book and on Twitter @mjeffreywright.

Follow Fuller Theological Seminary on Twitter at @fullerseminary.