One of my first posts on Patheos was about a conundrum Swedenborgians face – what to call ourselves (Swedenborgians, New Churchmen and Women, New Christians, etc.). Today I’m writing about a similar challenge, but one that goes a little deeper – namely, how to refer to the theological works penned and published by Emanuel Swedenborg.

The many names for Swedenborg’s theological corpus

There are lots of different ways to refer to these works. Growing up in the General Church of the New Jerusalem, the most common term was simply “the Writings.” That’s still the term I’ll use casually with long-time members of the faith. But it’s problematic for anyone who’s not familiar with the New Church. Just whose “writings” are we talking about? It can sound a little cultish.

In more formal settings – sermons, for example, or written articles – this body of work is often referred to as “the teachings of the New Church” or “the doctrine(s) of the New Church” or the “Heavenly Doctrine(s) of the New Church” (inspired by the title of the summary work The New Jerusalem and Its Heavenly Doctrine). These are better than “the Writings,” but they have problems of their own; notably, they’re still vague as to the origins of the work, and it is unclear that “the teachings of the New Church” refers to a very specific body of literature rather than just denominational statements of faith.

The third approach when quoting from these works is to cite the specific book that a quotation is from, rather than referring to the body of works as a whole; so, for example, I’ll write, “Arcana Coelestia expounds on this passage,” rather than, “The Writings explain this…” This works fine on a blog where I can provide a hyperlink to the work, but in just about any other setting it still leaves an obvious question: what is this book, and who wrote it? Which leads to the obvious follow-up question…

Why not just say, “Swedenborg says…”?

Isn’t this a pretty big fuss about semantics? Not everyone is averse to the straightforward formulation, “Swedenborg says” x, y, or z. The Swedenborg Foundation, for example, tends to put it that way in the blogs and videos I praised last week. And I confess that there are times when I put it this way myself.

But I try to avoid it. Because behind the question of how you refer to these works is the foundational question of what these works are. This is the question at the heart of some basic differences between different Swedenborgian denominations (yes, Swedenborgians have denominations). And the rallying cry of my denomination at its formation was, “The Writings are the Word of God.” It’s an affirmation that I stand by.

Swedenborg does not supersede Scripture

That’s an alarming claim for many Christians, and especially for sola scriptura Protestants. Doesn’t embracing anything besides the Bible as authoritative negate the authority of the Bible itself? I don’t think so – the Writings themselves assert that the Scripture of the Old and New Testaments must be the foundation for every doctrinal tenet. Arcana Coelestia goes so far as to say that it is better for a person to embrace a fallacy based on an incorrect reading of Scripture than to reject that fallacy before taking a “full view” based on the totality of Scripture:

For that which has been made of anyone’s faith, even if it is not true, ought not to be rejected, except after taking a full view; if it is rejected sooner, the first beginning of the man’s spiritual life is plucked up by the roots; and therefore the Lord never breaks such truth with a man, but as far as possible bends it. Let an example serve for illustration:

He who believes that the glory and therefore the joy of heaven consist in ruling over many, and from this conceived principle explains the Lord’s words concerning the servants who gained ten pounds and five pounds, that they should have power over ten cities and over five cities (Luke 19:11); and also the Lord’s words to the disciples, that they should sit upon thrones and judge the twelve tribes of Israel (Luke 22:30); if before taking a full view he extinguishes his faith, which is a faith of truth from the literal sense of the Word, he occasions the loss of his spiritual life. But if after taking a full view, he interprets these words of the Lord from His other words that “whosoever will be greatest must be the least,” and “whosoever would be the first must be the servant of all” (Matt. 20:26-28; Mark 10:42-45; Luke 22:24-27), if he then extinguishes his faith as regards heavenly glory and joy from rule over many, he does not occasion the loss of his spiritual life. (§9039)

Swedenborg constantly urges his reader to return to Scripture with prayer to the Lord Jesus Christ and an eye toward the two great commandments; with those as guides, he asserts, the reader will begin to see the true teaching of Scripture as he seeks to apply it to life.

If that’s the case, what’s the use of the Writings? For one thing, they provide additional detail (e.g. about life in heaven) that isn’t directly apparent in a literal reading of Scripture, even if it is hinted at or can be extrapolated. Beyond that, they provide a consistent doctrinal framework for reading the Bible. Others have pointed out the problem with thinking that it’s possible to read an objective “plain meaning” of Scripture. We all have interpretive lenses. I find that the lens provided in the Doctrine of the New Church allows me to see the Lord God Jesus Christ throughout the Bible in a way that I haven’t found with any other lens.

What Swedenborg claims about his works

Is there warrant in Swedenborg’s own work for suggesting that he thought of what he was writing as coming from God? I think there is. When Swedenborg first began publishing these works, he published them anonymously, as “a servant of the Lord”; he only began signing his name to them once his identity was discovered. In several places he claims that he wrote only what was from God; even in reporting dialog with angels and spirits, he claims omitted what God led him to omit, and included what God led him to include. Here’s how he put it near the end of True Christian Religion:

Since the Lord cannot show Himself in person, as has just been demonstrated, and yet He predicted that He would come and found a new church, which is the New Jerusalem, it follows that He will do this by means of a man, who can not only receive intellectually the doctrines of this church, but also publish them in print. I bear true witness that the Lord has shown Himself in the presence of me, His servant, and sent me to perform this function. After this He opened the sight of my spirit, thus admitting me to the spiritual world, and allowing me to see the heavens and the hells, and also to talk with angels and spirits; and this I have now been doing for many years without a break. Equally I assert that from the first day of my calling I have not received any instruction concerning the doctrines of that church from any angel, but only from the Lord, while I was reading the Word. (§779, emphasis mine)

This is the sense in which I see these works as the Word of God: not that they have the same depth of meaning as the Scripture of the Old and New Testament, but that they are God’s words to us, divinely inspired.

Differences of opinion

As I mentioned earlier, there are some fundamental disagreements between Swedenborgian denominations on this question of how to hold Swedenborg’s works. My denomination, the General Church of the New Jerusalem, continues to hold them as divinely inspired and authoritative. There’s a wider range of perspectives in the more liberal Swedenborgian Church of North America. Rev. Lee Woofenden, who served for many years as a pastor in the Swedenborgian Church, explains his own take. He lists his main points as these:

1. Swedenborg’s writings are not unquestionable, inerrant truth.

2. Swedenborg’s experience in the spiritual world was unique in known history.

3. Swedenborg’s inspiration from God was very different than that of the Bible writers.

4. Even if we don’t realize it, our understanding of the Bible depends on human teachers.

5. Swedenborg’s teachings are not an addition to the Bible; rather, they help us understand the Bible.

6. Only you can decide whether Swedenborg’s teachings are worth paying attention to for you.

Lee (and other Swedenborgian ministers) and I disagree on point number one, obviously, and it’s a pretty big deal to me. But that doesn’t stop us from having more in common than we do that separates us; for example, I’m on board with points 2 through 6, although we might differ on their specific meaning. I’m all for denominations working together, even while acknowledging our important differences.

Conclusion

To return to the question of terminology: I will continue to avoid emphasizing Swedenborg as the author of the Doctrine of the New Church, although I’ll mention his name for clarity. I don’t mind anyone referring to them as “Swedenborg’s works,” especially in work aimed at relative newcomers to Swedenborg; there’s precedent even in the Writings themselves for referring to divinely inspired works by the name of their human authors, e.g. referring to a passage from the Psalms as “in David,” or a passage from Deuteronomy as “in Moses.” But when I’m writing for New Church audiences, and even when I’m writing for others and can provide links to source material without mentioning Swedenborg by name, I will keep using the sometimes awkward formulations I mentioned at the beginning of this post. I personally find it helpful to be reminded that I’m not, I believe, writing about one 18th-century theologian’s opinions – I’m writing about something revealed by God.

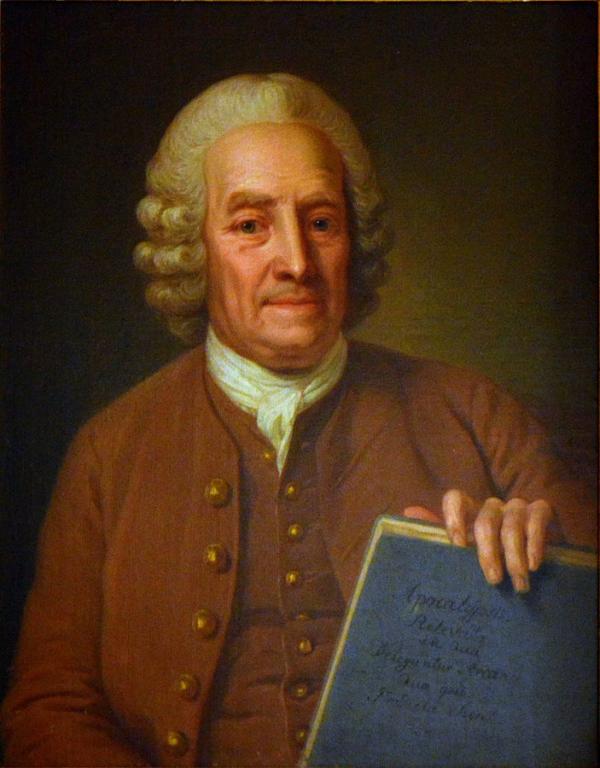

(Image by Per Krafft the Elder – Photograph: Esquilo, Public Domain, Link)