In the backseat of our minivan I swig an individual serving of white zinfandel to numb myself from the terror that is I-5: long sweeping curves, cement barricades, and massive trucks pulling two and three trailers that sway and rattle.

When I’m in the passenger seat, my husband can’t help but react to my cringing, so we agree a sleeping pill and $1.49 bottle of wine are reasonable for the five-hour trip from Eugene, Oregon where our daughter attends college, home to Puget Sound.

Ten years ago, living in San Francisco’s Bay area, I tried therapy. “You’re afraid of death,” the counselor said as if I thought being plowed into by tons of steel would result in a chipped tooth. I wanted driving—and life—to be predictable and safe.

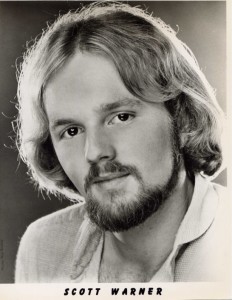

Tonight, when I awake after two drugged hours, my husband’s brother serenades us from the grave. Scott died eleven years ago yesterday of liver failure at age forty-five, the slow suicide of an alcoholic.

On my car stereo he is twenty-seven, performing at a San Francisco bar, and Kevin and I are newlywed college students with a portable cassette player, recording amid the chatter of patrons, the clatter of glasses.

Kevin burned a CD from tapes of such concerts for Scott’s memorial service in 2003. The sound quality, though poor, resurrects my brother-in-law: handsome, going places, his drinking still social.

“Begin the Beguine” launches the set. “To live it again is past all endeavor,” Scott sings. I hum along, his groupie, my voice recorded too. Then come lyrics popularized by Ray Charles: “And anyone can tell / you think you know me well / but you don’t know me.”

Scott—who’d played Jesus in Godspell—was living in an unheated New York City apartment trying to break into soap operas the year I met Kevin. A year later, discouraged, Scott moved back home with their mother, widowed when their father died of alcoholism (also at age forty-five), just when Kevin, the youngest, graduated high school.

Devoted to family, Scott sang at my wedding, played games with my children, called me his sister. He was an introvert and night owl who never held a traditional job. Just as he seemed on the verge of finding happiness as a train conductor and vaudeville singer for a railroad in the Santa Cruz Mountains where we all lived, he experienced a terrible setback.

While Scott was undergoing routine surgery, the anesthesiologist left the room—causing Scott to suffer anoxia that permanently damaged his short-term memory. My husband filed a lawsuit. The resulting award of a sum that reflected the “value” of Scott’s life was as dehumanizing as the alcohol he drank.

Hospital therapists recommended a residential program where Scott would learn to live independently. The legal settlement would pay the costs, but Scott refused. “If I have to go live with strangers, I’ll kill myself,” he threatened. So we watched his every move for a decade, trailing him along city streets, through supermarket aisles, outside when he went to smoke—not just so he wouldn’t get lost, but so he wouldn’t drink.

Despite our vigilance, he still managed as we said, “to get a bottle,” and the insults began: His sister was “a slut,” my children were “little brats,” my religious faith was “stupid.” The devoted uncle—who never missed an event in my daughter’s lives—downed peppermint Schnapps during intermission at school plays and dance recitals, changing from enthusiastic cheerleader to obnoxious heckler.

None of us escaped his criticism. What could we say? He wouldn’t—couldn’t— remember any of it.

My mother-in-law bought beer for birthday parties and barbeques, because we still wanted to be together, to celebrate our family where love, even more than geography, bound us—and because Scott was docile when he drank beer.

Coming from a multi-divorced family where people simply walked out when they were miserable, I appreciated the closeness and forgiveness my married family embodied, until I myself felt angry, powerless, worn doormat-thin.

I wrote Scott threatening letters (as if anyone is ever bullied into changing) but grudgingly didn’t deliver them—at the request of my mother-in-law and husband. I wanted Scott to suffer (as if he weren’t already), wanted him to remember the insults he hurled when drunk and repent of them. But most of all, I wanted him to save himself.

I settled for keeping our children’s performances secret from Scott, limiting family gatherings, and employing excuses to leave when the desperate slur crept into his voice, the drowning look into his eyes.

The last time he came to my house, twelve years after the botched surgery, he leaned on a cane, legs stiff with gout and diabetes. His hair had gone thin and greasy; he had dark hollows under his eyes and yellowed skin. His belly ballooned like a pregnant woman’s, swollen with fluid.

He reeked, not of the usual cigarettes, but unmistakably of death. He settled painfully on the couch. I offered him a glass of iced tea, and thought, “He can’t hurt me now.” He was hospitalized soon after, gone within weeks.

My plastic wine bottle is empty now. After a smattering of applause, the track changes.

I can’t say why some people reach for help and cling to sobriety, while others—like my own grandfather—reach, cling, and fall repeatedly, or why some, like Scott, spiral ever downward and only “hit bottom” through death.

His sweet tenor soaks the air with the Beatles: “I look at you all, see the love there that’s sleeping / while my guitar gently weeps.”

It’s easy—too easy—to love Scott now that he’s reduced to disc and memory.

We are dwarfed alongside the flank of an eighteen-wheeler, a great barricade jouncing in the darkness. Claustrophobia and panic threaten to rise. I close my eyes and pray—not for safety this time, but for forgiveness as my brother sings on:

“With every mistake, we must surely be learning.”

Cathy Warner is the author of the poetry volume Burnt Offerings(eLectio 2014). She serves as “Good Letters” Literary Editor, and earned an MFA from Seattle Pacific University. Cathy and her husband renovate homes hiring veterans through their business Yellow Ribbon Homes, and she leads writing workshops in West Puget Sound. Her website is cathywarner.com.