When I graduated from Seattle Pacific’s MFA program, I was sorely disappointed to hear Greg Wolfe announce The Brothers Karamazov as the next common reading selection. Upon returning home from my final residency at Whidbey Island, I pulled Dostoyevsky’s great novel down from the shelf as my first post-graduation self-assigned reading. It was such a decrepit old copy that it fell apart as I read, grew smaller as glue gave out and pages fell away—a visual gauge of my progress. When I finished, I had to go out and buy a new copy for my bookshelf.

When I graduated from Seattle Pacific’s MFA program, I was sorely disappointed to hear Greg Wolfe announce The Brothers Karamazov as the next common reading selection. Upon returning home from my final residency at Whidbey Island, I pulled Dostoyevsky’s great novel down from the shelf as my first post-graduation self-assigned reading. It was such a decrepit old copy that it fell apart as I read, grew smaller as glue gave out and pages fell away—a visual gauge of my progress. When I finished, I had to go out and buy a new copy for my bookshelf.

So I was delighted last month when, over brioche, fresh fruit, and coffee, the summer reading group I attend settled on The Brothers Karamazov for next summer. Though my teaching load is heavy, I have decided to read my way back through all my Dostoyevsky in preparation for our summer with Brothers. I have returned to Brothers and Crime and Punishment several times over the years, and I often teach Notes from the Underground in spring semester, so I’ve decided to start with Dostoyevsky’s books I’ve only read once.

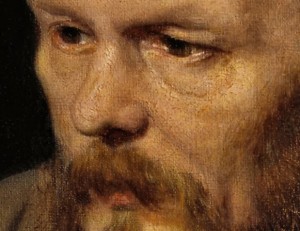

When I was a young man in my last year of seminary, I read Dostoyevsky for the first time. As many do, I started with Crime and Punishment; as maybe not so many do, I went on a Dostoyevsky bender that lasted through his novels and notebooks, to criticism and biographies. This eventually spread to Tolstoy, Chekhov, Pasternak, and then on to the likes of Berdyaev, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Unamuno, Camus. Dostoyevsky diverted me down a whole new stream of literature that I’ve been riding for the past two decades.

I am starting this time through with Demons. When I pulled it off the shelf, the top was so dusty it looked like powdered sugar, and brushing it off sent me into a sneezing fit. The jacket is pale yellow, and on the front, in black and red, rising from what could be a grave, or a building or a pile of lumber, are five men, one in a stovepipe hat, and the others in what look like imperial officer hats. Their faces are distorted, eyes tight, teeth bared in rage and madness. They are the possessed.

You might find this novel with the title The Possessed or The Devils (which is a more literal translation). Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, translators of the copy I have, chose Demons because they wanted the title to be a clear reflection of what they see as Dostoyevsky’s main concern: his focus is not so much the possessed, the men, but the demons that possess them.

When Dostoyevsky was a young man, he had renounced his Russian Orthodoxy for atheist materialism. “I have acquired the truth,” Pevear, in the foreword, quotes his telling another writer, “and in the words God and religion I see darknesss, obscurity, chains, and the knout.”

By the time Dostoyevsky wrote Demons he had suffered a great deal, and he had become a Slavophil, a reactionary standing against the progressive liberal ideas of the West, and a nationalist who believed the Russian Orthodox Church was the bearer of the one true God. In the novel, a character confronts another with words that echo Dostoevsky’s own famous assertion: “But wasn’t it you who told me that if someone proved to you mathematically that the truth is outside of Christ, you would better agree to stay with Christ than with the truth?” By the time he wrote Demons, Dostoyevsky’s own unequivocal answer to this question was yes.

In Demons the devils that possess the young men are ideas, “idea-demons”—rationalism, positivism, nihilism, materialism, socialism—and at the heart of all of them, Dostoyevsky places a kind of idea-Satan: atheism.

As I read the novel again, I cannot help but think about the state of our nation, the increasingly angry rhetoric in public life, the inescapable swirl of religion and politics, talk of persecution and resistance—even revolution. We appear to be hurtling toward what, in the words of the old Chinese curse, are ever more “interesting times.”

Dostoyevsky foresaw his country’s dark destiny with vivid prescience; however, his identification of atheism as the source of the problem was as mistaken then as it is today. Remember, when the Bolsheviks rolled into power there were thousands of Tolstoyan Christians across Russia endeavoring to live out a communal Christianity (the Bolsheviks purged them from the landscape).

When I was a young Baptist, Dostoevsky’s labeling atheism as the root of all his country’s woes made perfect sense to me. Now, not so much. It is not just anecdotal evidence that I’m working with when I say the atheists among us are found everywhere on the political spectrum that believers are, and are themselves most often kind and thoughtful human beings. If the root of “demon-ideas” today is not atheism, what is it? What would a demon idea even be?

To my thinking it is any idea that degrades and dehumanizes those who are not like us; it is any idea that makes scapegoats of the weak and defenseless; it is any idea that favors sending fleeing innocents back to almost certain torture and death; it is any idea that allies itself with the rich and powerful against the dispossessed.

Here is where the demons are. What is the source of these ideas? Not a belief or a lack thereof. These demons rise from a darker place. They spring from our own selfish hearts.

Vic Sizemore earned his MFA in fiction from Seattle Pacific University in 2009. His short stories are published or forthcoming in StoryQuarterly, Southern Humanities Review, Connecticut Review, Portland Review, Blue Mesa Review, Sou’wester, Silk Road Review, Atticus Review, PANK Magazine Fiction Fix, Vol.1 Brooklyn, Conclave, and elsewhere. Excerpts from his novel The Calling are published in Connecticut Review, Portland Review, Prick of the Spindle, Burrow Press Review, Rock & Sling, and Relief. His fiction has won the New Millennium Writings Award for Fiction, and been nominated for Best American Nonrequired Reading and a Pushcart Prize. You can find Vic at http://vicsizemore.wordpress.com/.