The (by and large quite good) Aeon magazine has a frustrating story on the question of whether God can lie and how it was supposedly the case that the Scientific revolution solved what had been hitherto a frustrating theological question. I say frustrating because it doesn’t contain outright falsehoods but does contain enough omissions and prevarications that a misleading impression is left.

As the piece itself eventually and grudgingly admits, classical Christian doctrine actually never had much of a problem answering the question: God is perfect; a sin is an imperfection; therefore God cannot commit a sin; therefore God cannot lie.

Now, what about those parts of Scripture where God certainly seems to be lying, or at least dissembling or dissimulating. As, again, the piece notes, many of those passages were read allegorically.

What about the rest? The piece makes it sound like there was a lot of hemming and hawwing. One answer has been to say that God is like a rhetorician: one who adapts his speech to the level of his audience, which is not the same thing as dissimulation and ill-intent. But this seems iffy, because the line between the rhetorician who merely adapts his speech and the sophist who misleads seems to get blurry in practice.

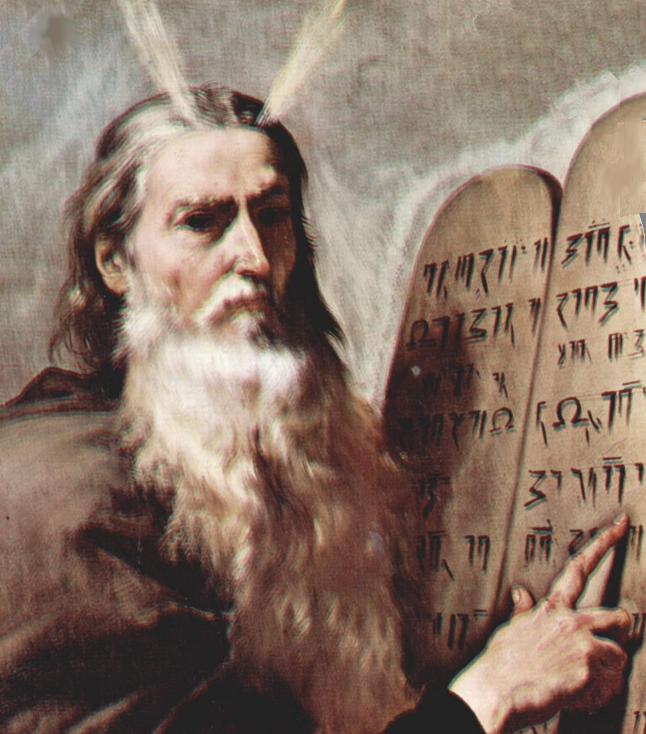

This is fair enough as far as it goes. But it’s striking that the piece never mentions a key image that is used throughout classical Christian theology–that of God as educator. This is the master image that Christian teachers have used to account for how God’s salvation plan unfolds in stages throughout Scripture, but without contradicting itself, in much the same way that a teacher or a parent will first present truths in a simplified form that a small child can understand before building on that foundation to impart higher and more complex truths. Not only is this not lying, but it is not even misleading or dissembling by any reasonable definition.

And this is, of course, an image drawn from Scripture itself. Jesus both represents himself and is represented by the Gospels as a teacher. Paul says that the Jewish Law was a paidagogos, a tutor. And perhaps most crucially, God is Father, and this is after all what fathers do.

Not that the piece is wholly without basis. Of course, there’s always been theological speculation, so you can always find a theologian somewhere playing around with some idea. Gregory of Nyssa’s ransom theory of atonement does seem to be premised on the idea that God can mislead at least the Devil (which is one reason why it was sharply criticized by later Christian teachers). But even then–the way I was taught ransom theory as a child was not that God actively misled the Devil, but that the Devil could not understand that Jesus was God made Man, because the Devil had shut off his heart to love and thus could not even conceive or imagine of the acrobatic act of love that is the Incarnation, until after the fact. Sin and evil is ultimately self-deception and self-imprisonment. In this, he was just like the apostles, mind you! Jesus told them over and over that he would have to be crucified and rise on the third day, and yet on Good Friday they still thought everything was lost.

The piece is correct when it says that Calvin and Luther straightforwardly said that God can and does lie, on account of his sovereignty. But–and this is the key thing the piece misses–this could happen only and precisely because they cut themselves off from the roots of classical Christianity and retreated to the hall of mirrors of literalistic Scripture readings unconnected from the mind of the Church. Now, voluntarism–the idea that God’s will is unconstrained by good and evil–did sometimes express itself in some Catholic theologians, but not as much as contemporary accounts make it seem (for example, Anselm is sometimes called a voluntarist, but I do not believe this to be true), but even then, it was always a minority opinion and never embraced by the Tradition.

And this points to the overall problem of the piece, which is that it is trapped in Modern secular prejudices and false dichotomies.

There is faintly the notion that an allegorical reading of Scripture betrays a discomfort with Biblical truth on the part of the one offering it, which vanishes once one realizes that classical Christian Biblical scholarship was fully open to the spiritual senses of Scripture. There is no awkwardness involved, to the contrary, in pointing out that Scripture cannot coherently describe God as being the one who laid the foundations of the world and also as changing his mind or being in the sway of emotions without the latter being poetic, or allegorical, or spiritual language; any cognitive dissonance caused thereby is the product of Modern literalistic prejudice and would have been foreign to the great exegetes.

This is actually a very important historical and exegetical point. In an era where the profusion of books is so immense that nobody can ever hope to read even a small part of all that is worth reading, we are accustomed to reading most books only once before moving on to the next one. Writers have been accustomed–trained–by this profusion to write books as straightforwardly, as literalistically, as possible. The competition for the reader’s attention is so great that one must grab the reader’s attention and make one’s meaning as plain and clear as possible. (We think the internet invented this, but you find complaints about this as far back as the Renaissance.) In an era where books were few and expensive, a book (especially a holy book, but any book) was something that the reader was expected to read many, many times over the course of her lifetime, and writers were therefore expected and understood to write densely packed layers of meaning that are intended to unfold so as to reward the twentieth reading as well as the first. There’s a reason why the classics are the classics. To us, the idea that a text’s deeper meaning might be different, even seemingly opposite, to its surface meaning, inevitably smells at least faintly fraudulent, but this is mere ethnocentric prejudice and historical ignorance; that idea was not only deeply acceptable, but even taken for granted by the Church Fathers (and, indeed, the rabbis).

And, finally, there is the false dichotomy that one must choose between the “God of the Philosophers” and the “God of the Bible,” between the absentee landlord, watchmaker God, and the anthropomorphic, mercurial Yahweh of Scripture. The answer, of course, is that there is more than one “God of the Philosophers” and more than one “God of the Bible,” and that the true God of the Philosophers and the true God of the Bible are one and the same. This is the genius (and deep truth) of the classical Christian synthesis: each account of God holds the other in check; of course, once one detaches oneself from this living Tradition, one is very liable to end up with either Charybdis or Scylla, but that just goes to show you shouldn’t do that.

But we get the same Gopnikesque line that once one has defined God with classical terms such as the fullness of being, prime mover, uncaused cause, etc. one can no longer believe in a God who intervenes in creation, without even seeming awareness that for millennia the authors of such classical definitions also proclaimed belief in an active God, and never saw any contradiction. (Maybe they were wrong, but you can’t show that without actually trying to engage what they actually said.)

It was supposedly the Scientific Revolution that solved the problem of whether God can lie (which, as we’ve seen, was never much of a problem) and made the anthropomorphic “God of the Bible” obsolete by leaving us instead with the Watchmaker God. But this is just not true. It is the Watchmaker God who is an anthropomorphic God–one who interacts with the physical Universe in the way that beings inside and part of that Universe do according to the laws of that Universe, instead of the fullness of being who is the transcendent source of the physical laws. This is what is said, for example, of Aquinas’s classical and apophatic definition of God’s omnipotence, not as the voluntaristic power to do whatever one likes, but rather as the fact that God is not subject to the physical laws of the Universe because He is their transcendent source. (Spoiler alert: Aquinas believed in miracles.) In the classical account, it is precisely because God is not one being inside the Universe but rather the transcendent source of all being, goodness and beauty that He is the source and mover of the laws of nature as well as the “intervener” and author of miracles. And, in turn, this is only unintelligible if one is in the grip of the Modern materialistic prejudice that material causality is the only form of causality.

Descartes and other Modern philosophers did put forward this Watchmaker, or Deist, picture of God but it is not at all clear what they were doing, or what they thought they were doing. Many if not most of the Modern philosophers wrote esoterically, and were as much engaged in philosophical inquiry as they were engaged in a political project to undermine the authority of the Church and of Christianity at large. It is by now well understood that Epicurus was an atheist and that when he wrote of the God or gods as too taken by the bliss of the Heavens to intervene in human affairs and that they should be ignored in practice, he was really trying to promote the idea that they don’t exist at all without suffering the fate of Socrates. We also know from Descartes’ private letters that he consciously intended much of his public writings to subtly undermine the theological and philosophical claims of classical Christianity.

I’m not yet decided on whether the Watchmaker God philosophers knew they were attacking, even creating, a totally false problem for polemical and political purposes, or whether they were simply ignorant. (Probably the answer is “yes.”) In any case, it is, to say the least, highly dubious to simply lump in Descartes’ God uncritically with classical Christian philosophical accounts of God. (Or, by the way, to reject him as an unabashed Deist, as some Christian philosophers are wont to do–I have had occasions to defend Descartes as well as to attack him.) Nowhere does the piece care to mention that orthodox Christians–and not just the dreaded “fundamentalists” who of course make their appearance–have consistently and universally regarded Deism as a heresy.

In the classical Christian account, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity is the divine Logos, or rational principle and mind, through whom everything was made and without whom nothing was made, and therefore, the laws of nature are an extension of the mind of God; knowledge of the laws of nature is knowledge of the mind of God; the use of reason is a participation in the mind of God. During the so-called “Athenian Renaissance,” natural philosophy was punishable by death (it was one of the counts of accusation against Socrates) because you might find out that Zeus doesn’t live on Mount Olympus after all; in the Medieval universities, natural philosophy was part of the core curriculum because it was believed that God was the transcendent source of the laws of nature, not a demiurge or a being inside the Universe. As Aquinas said, truth cannot contradict truth; natural philosophy is philo-sophy, a love for and participation in the Divine Wisdom (another deep and providential consonance between philosophical and Biblical language). And all of this was firmly place centuries before the Scientific Revolution.

To sum up, it is just not the case, as the subtitle of the article asserts, that science “made an honest man” of God. Theology did that just fine on its own–and provided the metaphysical grounding for science to flourish in the process.