“Story” is an extremely useful tool for clarifying our key ideas and bringing focus to our message. This won’t make sense to some people. Whatever you think about “story,” set that aside for a moment.

The word “story” conjures contrary reactions among missionaries and theologians. Some see “storying” as a critical tool for sharing the gospel; others are more cautious, unsure of the relationship between story and theology.

Scientists and Theologians Need Story

The release of Star Wars popularized the search for a universal story structure. George Lucas applied Joseph Campbell’s research concerning “The Hero’s Journey,” a story pattern found in myths across human history.

In recent years, people like Kendall Haven and Randy Olson have noted the inability of scientists to communicate their findings to a broader community. These men left careers as profession scientists in order to understand how story works and so help fellow scientists more effectively communicate their ideas.

But scientists aren’t the only people who have a hard time conveying their thoughts. Anyone who teaches the Bible often struggles with simplify complex ideas but without dumbing down the content.

We want structure but without systems

Many people assume theology must be systematic. They regard story as something different than theology, perhaps its background or a tool for illustration. But what they forget is that stories have structures. They’re not mere loosey-goosey compilations of detail in need of analysis.

Anytime we hear a story, we all have certain expectations. Different genres have distinct unwritten rules. Ever watched a romantic comedy? Arguably, then, you’ve seen them all. That’s not exactly true but it feels like it because romantic comedies rarely disguise their structure. Other story-genres (e.g., mystery, action adventure, Disney princess movies) are no less structured.

Explanations are not stories. Think about it––what makes a bad story? When people drone on, when they seem to have no purpose or sense of direction. They essential say, “This…and this…and that…and this other thing….”

Syllogisms are not stories. I love tight, logical arguments, but honestly, we know that logical syllogisms are far less effective in persuading people that stories. Blame this on the “Fall” is you like, but stories are the inherent structure of human experience. No wonder people generally regard stories as being more interesting, memorable, and practical.

The DNA of Story

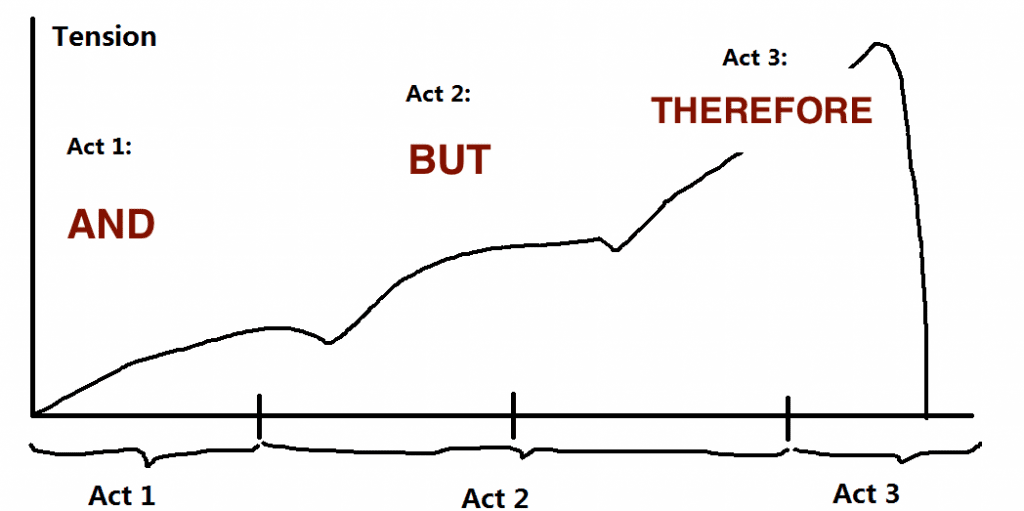

Randy Olson identifies the most basic structure of any story. Whatever the plot variation and complications of a story, we always find a similar ABT pattern. Olsen says, “ABT is the DNA of story.”[1]

What is ABT? It stands for And…But…Therefore.[2]

And –– represents the basic fact, context or circumstance of a story.

But –– signifies the story’s complication or problem(s) to be overcome.

Therefore –– refers to the conclusion of the story. It highlights what must be done to overcome the challenge presented by the “but.”

Like scientists, Christians sometimes forget to think about and explain why some idea matters. Pragmatists overreact to this problem by minimizing rigorous theology, regarding it as abstract or impractical. Therefore, theologically-minded people further insist on the importance of theology, since the Bible and thinking are both important.

ABT can resolve this impasse.

This structure is memorable. It’s built into our minds through the hearing of stories. We don’t want a list of facts. We want to know why certain fact matter. What problems emerge amid said facts and what should we do about them? However, ABT helps us do more than simply tell good stories.

The ABT structure clarifies our thinking and communication, even if we do not explicitly tell “stories.”

But what does this look like?

Anyone familiar with Haddon Robinson’s Biblical Preaching knows the value of finding “the big idea” when preparing to preach. Robinson tells students to identify the one major idea you want to communicate and state it in a single sentence. It’s harder than you might think. But it is incredibly useful! The ABT structure similarly helpful.

Here are a few examples:

- We have the gospel AND all need it BUT few grasp its meaning or significance SO we must contextualize.

- Contextualization includes communication AND application BUT starts with interpretation SO we should teach exegesis and biblical theology.

In this post, I’ve used multiple layers of ABT. For example, at a big-picture level, my argument looks something like this:

- Many people struggle to communicate complex theological ideas AND they think theology is systematic and abstract. BUT story has an inherent structure that is memorable and meaningful. THEREFORE, we should use the ABT structure to clarify our thinking and teaching.

So what can I do from here?

Notice that the 3 examples above are not overt stories in the sense of “Once upon a time….” However, they do contain an implicit narrative about the world. They reflect our lived experience, with problems and a call to action.

AND

We cannot convey a thought that is not clear in our minds. One reason we communicate so poorly is because we don’t always know what we want to say.

BUT

After years of thinking of theology and doctrine in systematic terms, it’s doubtful we will naturally and clearly present our ideas consistently in a way that makes sense to others.

THEREFORE

I recommend you use the ABT structure to simplify your idea in your own head. The process will help you organize your thoughts. Then practice using it whenever you prepare a lesson, write a blog post or article, and prepare a message. Although you might not reveal the ABT structure so overtly, ABT will ensure you will convey your ideas more coherently and concretely.

I look forward to hearing your stories.

Below is a fuller presentation by Randy Olson explaining ABT.

[1] Randy Olson, Houston, We Have a Narrative, p. 17.

[2] You can substitute other words. For example, I like ABS, meaning “And…But…So”.