Thomas Albert Howard and Karl Giberson:

This spring semester, California’s Biola University, among the nation’s largest evangelical institutions, opens the doors of its ambitious new Center for Christian Thought. Resembling institutions such as Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, Biola’s center seeks to bring a mix of senior and postdoctoral fellows to campus to collaborate with internal fellows and faculty.

Is the launch of Biola’s Center for Christian Thought a victory lap for American evangelical intellectual life or at least another level attained on the purgatorial ascent toward intellectual respectability?

The center is unusual in operating from a distinctly Christian vantage point. The mission statement is forthright: “The Center offers scholars from a variety of Christian perspectives a unique opportunity to work collaboratively on a selected theme…. Ultimately, the collaborative work will result in scholarly and popular-level materials, providing the broader culture with thoughtful Christian perspectives on current events, ethical concerns, and social trends.”

Biola’s center is the latest chapter in a comeback of the “evangelical mind.” While serious scholarship by self-professed evangelical Christians did not disappear entirely in the 20th century, it went into eclipse in the postwar period. These decades, especially 1960-1980, saw the high-water mark for Western secularism when, contrary to subsequent evidence of religion’s persistence, Time Magazine in 1966 asked on its cover “Is God Dead?” Social scientists in The New York Times confidently predicted in 1968 that “by the 21st century religious believers are likely to be small sects, huddled together to resist a worldwide secular culture.” …

All of this has begun to change in the past quarter century: evangelical Christians have been shedding their “fundamentalist baggage” and reclaiming a place within deeper traditions of Christian learning and at the table of American cultural life. Signs abound of this recent shift, clearly in evidence by the mid-1990s. In 1994 Mark Noll (formerly of Wheaton College in Illinois, now holding an endowed chair at Notre Dame) published The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, calling evangelicals to repent of past anti-intellectualism and honor the Creator of their minds with first-order inquiry and creative expression. The book became a manifesto of sorts for younger evangelicals attracted to the life of the mind. Nineteen ninety-four also witnessed the publication of George Marsden’s The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief, analyzing the secularization of mainline Protestant universities and offering a blueprint for revitalized “Christian scholarship.” …

In 1995 the journal Books & Culture, was launched; it has become a leading organ of evangelical thought. Significant funding initiatives of the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Lilly Endowment — such as the Lilly Fellows Program at Valparaiso University — also empowered a new generation of engaged Christian scholars, including evangelicals. These developments together with the influence of scholars like Wolterstorff and Plantinga, and the emergence of evangelical Christians into key places of academic leadership — such as the presidencies of Nathan Hatch at Wake Forest and Ken Starr at Baylor — put a new face on evangelicalism. As such, it bears little resemblance to your grandmother’s backwoods open-tent revival anymore, but represents, to quote the title of a much-regarded book by D. Michael Lindsay, president of Gordon College, Faith in the Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite….

But beyond the problem of Mr. Worldly Wiseman is the problem of Biola itself. The problem of Biola, however, is not the problem of Biola alone; it is shared by a number of the more than 115 evangelical schools in the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU), the largest umbrella network of evangelical institutions of higher learning. The problem is, quite simply, lingering attachment to some of the more dubious certainties and habits derived from Fundamentalism and hardened by the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversies of the 20th century.

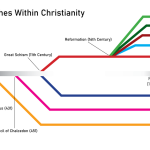

This presents two acute problems for the emerging evangelical mind. First, in a well-intentioned effort to avoid “scientism” — the belief that all knowledge claims must conform to standards of evidence found in the “hard sciences” — it perpetuates skepticism about science itself. Second, lingering fundamentalist accents put these institutions in a deficient and compromised position vis-à-vis more venerable and enduring resources of fides quarens intellectum, faith seeking understanding — traditions going back to the seminaries of the Reformation era, the universities and monasteries of the Middle Ages, and the earliest formulations of Christian teachings in the creeds and councils of the early church.