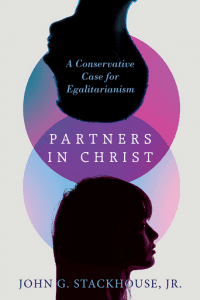

The issue is not if one is to be an egalitarian but how to be an egalitarian. (Not disrespecting that complementarians believe the same about themselves.) The issue John Stackhouse addresses in a chapter called “What Then?” (the book is called Partners in Christ) is how to be an egalitarian in a Christian manner. This is how he states the problem itself:

The issue is not if one is to be an egalitarian but how to be an egalitarian. (Not disrespecting that complementarians believe the same about themselves.) The issue John Stackhouse addresses in a chapter called “What Then?” (the book is called Partners in Christ) is how to be an egalitarian in a Christian manner. This is how he states the problem itself:

As we seek to respond properly to a social situation involving patriarchy—whether a marriage or a church, in the instances discussed in this book—there are a number of principles that can guide us (127):

He will outline four guiding principles that ought to guide the Christian who is egalitarian.

First, activism.

His theory is that we should be active for the Shalom of Jesus, and that means “we should further the flourishing of human society by the fullest possible participation of women and men, without prejudice or constraint. … We are, instead, called to do what we can to extend the kingdom of God. So if we get any chance to improve a marriage or a church, we should (127). [Brother John, friend, and much-honored professor, I’ll leave that Kuyperian-Niebuhrian-realism view of kingdom alone in this post.]

Second, realism. [This is John Stackhouse’s theory of how Christians are to live in this world and relate to culture and face the capacity for change, transformation and church life.]

Again, he defines realism as loving God and loving neighbors as ourselves (the Jesus Creed). But what does this mean in a realism framework? John has an important book on this topic — blogged about on this site years back — called Making the Best of It.

Given a particular set of circumstances, what does God want to happen? Given what the limitations seem to be, what are God’s priorities? Given who the neighbors are in this case, in what ways can I love them, and in what ways will they let me do so? Such realism will help us make the necessary hard decisions in a world in which we typically cannot succeed in everything we attempt, a world in which we frequently have to settle for half a loaf, a world in which we often confront a conflict of values and have to work for the higher at the cost of the lower (127-128).

Third, vocation.

John contends we are called to follow Christ, to do what we are called to do, not to do what we are not called to do but God is also calling the church to do what the church is called do in this world — and we part of that mission of God in this world.

Fourth, hope. Very important words here:

God gives us immediate hope that our current labor, however vexed by suffering, will produce lasting results as it is validated and assisted by him. God also gives us the great final hope that soon our suffering will cease, that injustice will be terminated, and that Christ will return to establish his kingdom of lasting shalom (128).

John Stackhouse then works out how this works out. We begin in our churches with better marriages and better families and better fellowships of gendered Christians.

Some will not be heard (here his realism comes to the fore). At times illusions of change must be shifted to subtle improvements through faithfulness over time. He does believe the Spirit can transform but he is not living in a utopian ideal world now.

Pushing too fast or too far in a given setting may cause more damage than good. [OK, but sometimes rupture is what is most needed, right?] God wants shalom, on that we agree. At times the policy is slow, steady progress — and I agree on that. But John knows this well: at times, the slow, steady theory is actually the “don’t change the status quo” theory. Here is how he puts it:

So in some circumstances the policy needs to be slow, steady pressure on a marriage or a church to change, with appreciative cooperation with all of the genuine work the Spirit is doing therein. We must be careful not to run ahead of the Spirit of God (129).

Because he’s aware that this issue is about marriages and not just women in ministry, he speaks about abuse — which is not the same as some difficult relationships in marriage. Here are his words:

Someone suffering abuse, I should make plain, should free herself or himself from it if she or he possibly can. No proper Christian teaching about suffering in general, or about voluntary subordination within marriage or church, can bless abuse by telling people to stay in such situations if they can escape them. We especially must guard against the tolerance of abuse “for the sake of the church’s reputation’1 or “for the sake of the pastor’s reputation”—for abuse happens in Christian and even clerical homes as well, and it must be rooted out there as it must be rooted out everywhere else (130).

But God calls some to a more activist posture and others to a more cooperative posture.

Remember this: love one another.