In chapter six of Adam and the Genome Scot McKnight starts by outlining the ancient Near Eastern context of the biblical creation narratives, including those in Genesis 1-3. Several texts have come to light a few in a variety of forms. Scot considers Enuma Elish, Gilgamesh, Atrahasis, and the Sumerian version of the Atrahasis creation story. There are others that could be brought into the discussion as well. The point is not that the biblical authors copied the narratives of the other communities, including Mesopotamia and Egypt, but that many of the ideas contained in the myths were part of the “common knowledge” of the original authors and audience. Some ideas show up in the biblical narratives because they were simply known and others are being explicitly countered and repudiated. Both the similarities and the differences can direct us toward the most important themes in the narrative.

In chapter six of Adam and the Genome Scot McKnight starts by outlining the ancient Near Eastern context of the biblical creation narratives, including those in Genesis 1-3. Several texts have come to light a few in a variety of forms. Scot considers Enuma Elish, Gilgamesh, Atrahasis, and the Sumerian version of the Atrahasis creation story. There are others that could be brought into the discussion as well. The point is not that the biblical authors copied the narratives of the other communities, including Mesopotamia and Egypt, but that many of the ideas contained in the myths were part of the “common knowledge” of the original authors and audience. Some ideas show up in the biblical narratives because they were simply known and others are being explicitly countered and repudiated. Both the similarities and the differences can direct us toward the most important themes in the narrative.

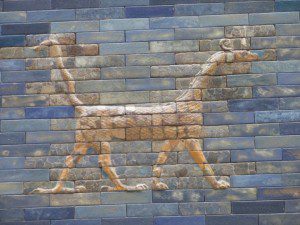

Creation was not the result of a divine battle, with the winner making humans to perform the work the lesser gods despised. Gods do not come and go, they do not hunger, kill each other and assume or lose power. All of these are standard themes in the ancient Near Eastern literature. Marduk, the god of Babylon assumes dominance in many of the stories we have – but not in all. It depends which community was telling the story. The image to the right is Marduk’s symbol animal from Nebuchadnezzar II’s Ishtar Gate in Babylon.

Creation was not the result of a divine battle, with the winner making humans to perform the work the lesser gods despised. Gods do not come and go, they do not hunger, kill each other and assume or lose power. All of these are standard themes in the ancient Near Eastern literature. Marduk, the god of Babylon assumes dominance in many of the stories we have – but not in all. It depends which community was telling the story. The image to the right is Marduk’s symbol animal from Nebuchadnezzar II’s Ishtar Gate in Babylon.

Scot puts forth twelve theses that can help to guide our reading of the biblical creation narratives as the word of God. The first three look at creation, the next seven focus on the role and purpose of humans, while the final two focus on Adam and Eve as individuals. In this post I want to focus specifically on the first three theses. The others will be covered in subsequent posts.

It is God’s Story.

Scot doesn’t put it quite like this (although I think he’d agree), but I’ve come to believe that the most important point we must remember when reading Scripture is that this is God’s story. The Bible is not a collection of stories of heroes or a record of human accomplishment. In fact, by and large it is a narrative of God’s faithfulness, even in the presence of repeated human failure. Through this narrative we learn what is expected of us, and we find a handful of excellent role models (but fewer than you might expect), but primarily we learn about God’s mission in the world.

Scot doesn’t put it quite like this (although I think he’d agree), but I’ve come to believe that the most important point we must remember when reading Scripture is that this is God’s story. The Bible is not a collection of stories of heroes or a record of human accomplishment. In fact, by and large it is a narrative of God’s faithfulness, even in the presence of repeated human failure. Through this narrative we learn what is expected of us, and we find a handful of excellent role models (but fewer than you might expect), but primarily we learn about God’s mission in the world.

The first thesis for reading Genesis 1 in context focuses on God.

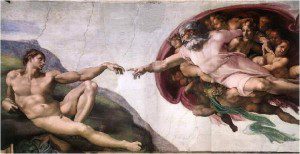

God is one, and this God is outside the cosmos, not inside the cosmos as the gods of the ancient Near East are. … Genesis 1-2 are more about God than Adam and Eve or the creation of the world. (p. 119)

The God of Israel, portrayed as creator of the world is profoundly different from the gods of the surrounding cultures. Unlike the warring, worrying, and/or worn out divine pantheon of the ancient Near East, God is in control of creation from beginning to end.

God creates by a word deriving from God’s own sovereign choice. The fundamental event of Genesis 1 is God saying, “Let ther be,” and there is. The waters may be primal chaos, but the waters are easily and simply subdued by God’s own command. … This God is transcendent and exceedingly powerful, exalted above creation and responsible for all of creation; this God, then, is not part of the created order but outside and over the created order. All of the gods of the ancient Near East are eliminated in the theology of Genesis 1, and one supreme God, YHWH, is left standing. (p. 119)

As Christians we can go a step further and connect creation with Jesus, the son as well (1 Cor. 1:24, Col. 1:15-20, Heb. 1:1-4, John 1:1-4).

The second thesis addresses the occasional references to conflict in biblical texts of creation (eg. Ps 74:13-16). Because we wish to take the Bible seriously on its own terms, we will not deny or hide the hints of conflict. However, neither creation nor the man and woman (Adam and Eve) are the result of conflict among the gods. With respect to the passage from Psalm 74, Scot writes:

The second thesis addresses the occasional references to conflict in biblical texts of creation (eg. Ps 74:13-16). Because we wish to take the Bible seriously on its own terms, we will not deny or hide the hints of conflict. However, neither creation nor the man and woman (Adam and Eve) are the result of conflict among the gods. With respect to the passage from Psalm 74, Scot writes:

This is where the principle of respect and honesty come into play: one can suspect that the psalmist is using ancient language to express something he knows better, or one can suspect that the author shared those ideas. Either way, the Bible forms a marvelous parallel with the ancient Near Eastern literature, while it offers a significantly different theology of creation: Israel’s God conquered the forces of evil in creation because those “gods” were not capable of resisting the one true God.

… One need not assume that the ancient Hebrews embraced the fullness of anything like the Tiamat myth when they refereed to Leviathan, but one should at least admit that mythical themes and language have some role in the Bible’s creation accounts. (p. 123)

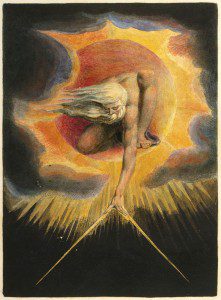

Scot also refers to Richard Middleton’s work in The Liberating Image. Rather than a conflict motif and a warrior god, we see in Genesis 1 a God who creates as an artist creates. God is a divine artist rather than a divine conqueror. He doesn’t pull out a sword and charge into battle. In fact, if there are hints of conflict in Genesis 1 (sometimes suggested in formless and void), “God conquers not by counter violence but by ordering and creation through his artful work and word.” (p. 124)

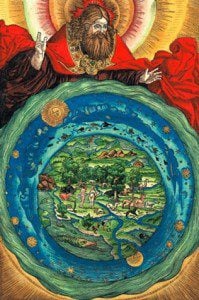

The third thesis deals with the purpose of creation. “God orders creation into a temple. Adam and Eve are designed by God to worship and to lead all creation to see its God.” (p. 124) In this view creation out of nothing is not taught or denied in Genesis 1, it simply isn’t terribly important. “Genesis attempts to show not so much that God created the world out of nothing but that God ordered all creation for a purpose.” (p. 124) John Walton and others have emphasized the temple motif and the theme of ordering. (In addition to Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One, The Lost World of Adam and Eve, Scot references Jon Levenson, Creation and the Persistence of Evil, and Bill Arnold, Genesis.)

The earth, then, is not designed as a scene of conflict but a scene of worship. The gods are not fighting for control, because God is in control. All of creation is designed not for humans but for God, and all things on earth are called to worship this one true God. In worship of the one true God, all creation is subdued. (p. 127)

This plays against the narrative of scientific materialism in the twenty first century just as effectively as it did the divine pantheon and myths familiar to the original audience. The earth is not random, without purpose, rather it is created for a purpose – “in worship and service of God, others, and the rest of creation, we enter into God’s purpose for all of creation.” (p. 127)

This is God’s Story. God created out of his own sovereign choice. He didn’t need to subdue a foe to earn the right to create, nothing stands against him. God created as a artist creates a masterpiece. The purpose of creation is the purpose of a temple, a place for worship. All of creation belongs to God.

In what way is God the focus of Scripture?

In what way is he the focus of the creation narratives of Scripture?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail [at] att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.