In Mark Jesus does not work alone. As weak and lacking in understanding as his followers are, he needs them. He needs to establish a kingdom in this world – not of the world but definitely for the world. It will be an alternative community to the kingdoms of this world, a government in exile. To its first members he gives the title apostles. Eighth in a series on “The Worldly Spirtuality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and a Table of Contents are HERE.

A Christian spirituality can’t be unworldly. It can’t deny the value of the material world created by God and entered into by Jesus. At nearly every point in Mark’s story, Jesus has been engaging the worldly powers of his Jewish/Roman world–engaging and withdrawing in turns. Now he breaks the pattern of retreating to obscurity after a confrontation.

Jesus again enters a synagogue on the Sabbath. (Mark 3:1-6) In this public space “there was a man with a withered hand.” “They” — later we see they are Pharisees — are watching to see if he will cure on the Sabbath. Jesus gets no answer to his question, “Is it lawful to do good on the Sabbath or to do evil?” Angry (again) Jesus tells the man to stretch out his hand, and he is cured. The Pharisees go out and plot with leaders who align with Herod to put Jesus to death.

Mark uses the phrase “hardness of heart” to describe the Pharisees. Myers notes that eventually Jesus’ disciples receive the same description, to the discomfort of Mark’s own readers. (Myers, 162) It’s no part of Mark’s task to divide people into opposing camps, though he will soon set up a “camp” of sorts.

Choosing the Apostles, the leaders of the campaign

Now Jesus withdraws from the confrontation but not from the public. Crowds of people from all over follow him as he continues to cure many diseases and cast out devils. Mark names the many places from which the people come; effectively it’s “from North, South, East, and West.” (163) The campaign is getting really big. Jesus finally makes it to the seashore. He has to put out in a boat a little way from shore so the crowds won’t crush him as he teaches them.

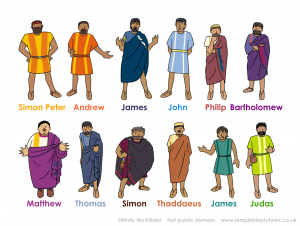

Jesus’ next symbolic action (3:13-19) is to go up a mountain, like Moses. There he will form the beginnings of a new community, “the twelve.” He cements their identity with a special name, “apostles,” specifying what they are to do. They must carry on Jesus’ mission of preaching and casting out devils. This mission must continue when the “Bridegroom is taken away.” Simon and the brothers James and John get new names, respectively, Peter (or Rock) and Sons of Thunder. They are a kind of inner circle.

The twelve are not an exclusive group. Levi, whom Jesus called earlier, is not named and several whom Jesus names never appear again in this Gospel. I note that Matthew’s Gospel has the call of Levi story except that “Levi’s” name is Matthew, the name of an apostle. Early commentators explain that the same person must have had two names. I’m not so sure. The desire to find consistency in the Bible seems to motivate that explanation.

At any rate, the number 12 is symbolic of the 12 tribes of Israel, the chosen people, whom Jesus intends to reform. The apostles, or at least Mark’s readers, haven’t heard yet what kind of alternative community Jesus intends to make. But Mark does let them know that it won’t be safe. The last apostle Jesus named is Judas Iscariot, with the auspicious description: “who betrayed him.”

Myers sums up:

Jesus, having repudiated the authority of the priestly/scribal order, now forms a kind of vanguard ‘revolutionary committee,’ a ‘government in exile’! The community of resistance has been founded. (Page 164)

Image credit: Tribe Church