Check this out, from last month:

Scientists have studied the San people of Southern Africa for decades, intrigued by their age-old rituals and ancient genetic fingerprints. Now, after more than a century of being scrutinized by science, the San are demanding something back. Earlier this month the group unveiled a code of ethics for researchers wishing to study their culture, genes, or heritage.

You can read the full San Code of Research Ethics for yourself. But I was struck, as I read this story, by the detail that this is the very first time an indigenous African group has created a code of ethics for researchers.

The San are not the first indigenous population group to impose such codes on research. The Aboriginal Australians and Canada’s First Nations and Inuit have drawn up similar codes, which standardize consultation, the benefits due to participating communities, and data storage and access. But this is the first research code produced by an African group.

The San people have been the subject of research for many years, and this research has generally been imposed on them by western researchers, rather than conducted with their input and involvement. The San want to play a greater role in the development of research proposals, and in reviewing study findings.

In thinking about how western scientists conduct research on “other” groups and cultures, I’m reminded of the 1956 article, Body Ritual among the Nacerima.

While each family has at least one such shrine, the rituals associated with it are not family ceremonies but are private and secret. The rites are normally only discussed with children, and then only during the period when they are being initiated into these mysteries. I was able, however, to establish sufficient rapport with the natives to examine these shrines and to have the rituals described to me.

The focal point of the shrine is a box or chest which is built into the wall. In this chest are kept the many charms and magical potions without which no native believes he could live. These preparations are secured from a variety of specialized practitioners. The most powerful of these are the medicine men, whose assistance must be rewarded with substantial gifts. However, the medicine men do not provide the curative potions for their clients, but decide what the ingredients should be and then write them down in an ancient and secret language. This writing is understood only by the medicine men and by the herbalists who, for another gift, provide the required charm.

The charm is not disposed of after it has served its purpose, but is placed in the charmbox of the household shrine. As these magical materials are specific for certain ills, and the real or imagined maladies of the people are many, the charm-box is usually full to overflowing. The magical packets are so numerous that people forget what their purposes were and fear to use them again. While the natives are very vague on this point, we can only assume that the idea in retaining all the old magical materials is that their presence in the charm-box, before which the body rituals are conducted, will in some way protect the worshiper.

Beneath the charm-box is a small font. Each day every member of the family, in succession, enters the shrine room, bows his head before the charm-box, mingles different sorts of holy water in the font, and proceeds with a brief rite of ablution. The holy waters are secured from the Water Temple of the community, where the priests conduct elaborate ceremonies to make the liquid ritually pure.

The article was constructed as a piece of satire, meant to mimic the distance with which anthologists approach native groups by demonstrating how an anthropologist might write about American culture when using the same approach. The shrine described above is a medicine cabinet, and the font is the bathroom sink. The piece points to the limits in outsiders’ understandings of a culture, and to the eroticization western researchers often engage in when conducting research on non-western cultures.

The San Code of Research Ethics includes the right of the San people to review findings before publication, in part to provide feedback for accuracy, in case the researcher has misunderstood something.

I’m also reminded of this recent twitter exchange:

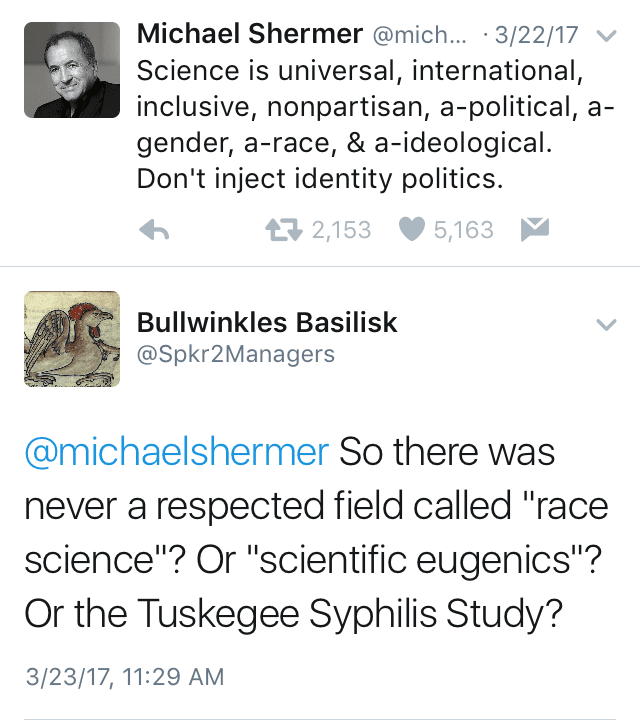

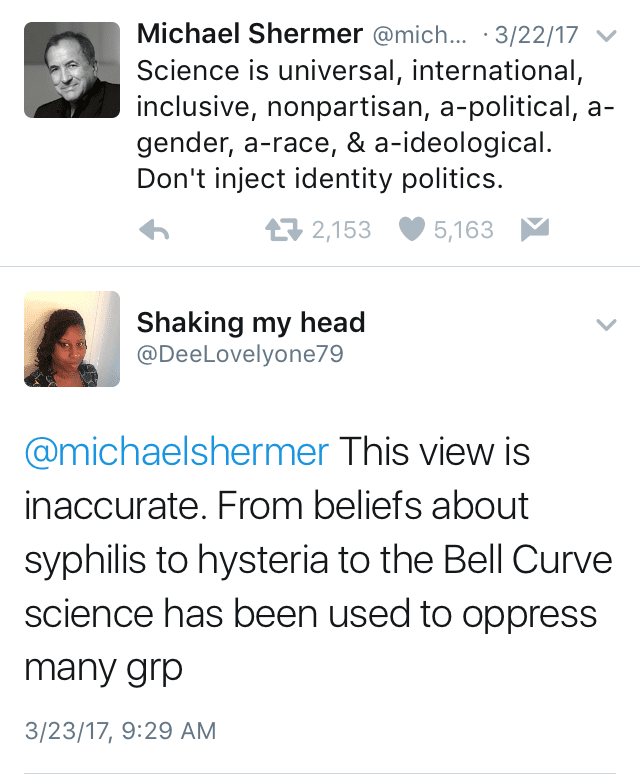

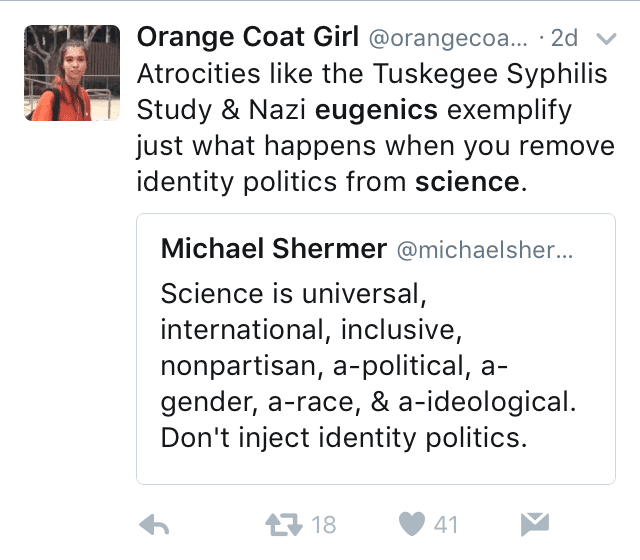

Text of tweet by Michael Shermer:

Science is universal, international, inclusive, nonpartisan, a-political, a-gender, a-race, & a-ideological. Don’t inject identity politics.

Text of response tweets:

So there was never a respected field called “race science”? Or “scientific eugenics”? Or the Tuskegee Syphilis Study?

This view is inaccurate. From beliefs about syphilis to hysteria to the Bell Curve science has been used to press many grp

Atrocities like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study & Nazi eugenics exemplify just what happens when your move identity politics from science.

Science, as conducted by researchers, is not automatically inclusive, accurate, or beneficial. Fortunately, scientistic bodies have learned from the past, and Institutional Review Boards help set standards for scientific research on human subjects. Statements by the San and other groups are a step forward in ensuring that research is fair, accurate, and not exploitative.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!