It’s a conversation I remember vividly, last April, standing outside Lil D’s school after I had drove him to school and walked him to his classroom. A conversation I had with a mother of a fellow classmate about if public school was good for our children.

It’s a conversation I remember vividly, last April, standing outside Lil D’s school after I had drove him to school and walked him to his classroom. A conversation I had with a mother of a fellow classmate about if public school was good for our children.

Slowly, the routines we had been building for years and celebrating as a normal part of his day were dissipating. He was in his fifth and last year in his public school (in a self-contained autism classroom), and each day was fraught with anxiety, self-injury, crying, head banging and withdrawal from the world.

His teachers at school, therapists at home, his pediatricians and specialists I was taking him to – we were all desperately trying to figure out why. Why? Why?

And, the transition to middle school was looming ahead like an inevitable thundercloud of change, uncertainty and unknown – all the hallmarks of an Autism Perfect Storm, upon whose waves we were already being tossed to and fro.

Last spring was a blur of IEP meetings, frantic emails and calls with his teachers, letters and calls to the our county’s special education department and more meetings as we crawled up the bureaucratic ladder in our push to have our son transferred to a private school. We didn’t have any major issues with his teachers or how his teachers and administrators were trying to manage the situation.

We loved his school and his staff. We knew they were trying their best. But their best wasn’t enough.

We needed everyone to acknowledge one hard fact: Lil D could not be taught there anymore. He was beyond their educational capabilities, and they had to do right by him and place him somewhere where he could be taught.

And, they did right by Lil D.

It was during all this that I had that conversation with my friend, whose child was in Lil D’s class. Knowing what we were going through, she asked if I had been pleased with Lil D’s years in the school, if he had learned and accomplished what I had hoped for. She asked me if I thought private autism school would be better for Lil D.

I told her the truth: This was a very bittersweet situation for us. On one hand, to get private school placement through the public school system is a very difficult, near impossible thing to do. Things have to be bad, but more than that, you have to be able to convince the county that they aren’t doing right by your kid and thus must fork over the dough to place him in a private school that can provide education and behavior management.

The difficulty of accomplishing that, my friends, is beyond the descriptive power of my similes and metaphors and figurative language . It’s a process that involves blood, sweat, tears and often lawyers.

We got Lil D private placement through the county. So I should’ve been celebrating, right?

I was, and I wasn’t. At the risk of alienating myself from friends (and people I don’t even know) who have struggled against a bad school or a stubborn team of teachers and administrators to find the best situation, a private school placement, or heck, just a safe and healthy learning environment for their child – we weren’t in an adversarial situation with Lil D’s public school.

Though he had failed to make any decent progress in his IEP (individualized education plan), which at one point pushed us to consult a lawyer to see if we could place him in a private autism school and sue the county to pay for it, we kept him there for one main reason .

Social Interaction and Integration.

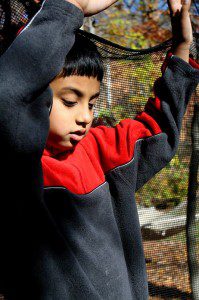

Lil D, with the severity of his autism, has no real friends beyond his siblings and his therapists. But at his public school, he had learned to navigate the halls with nearly 700 students. Although he was in a self-contained classroom, he was able to join his peers for recess, music class and gym (during some years). In his last two years there, his teacher organized a “lunch bunch,” where groups of fourth and fifth graders (who vied for this privilege) came and had lunch with him in his classroom, playing games with him.

I don’t mean to over-glorify this. None of this elicited real friendships. He never received a birthday party invitation in his five years there. He wasn’t asked to participate in any playground fun. He was, he is, a severely, nonverbal autistic child who doesn’t seek friends beyond his family.

But, he was accepted as member of the school. He was (as far as I know), never made fun of, never bullied (again, as far as I know, because if he was, he wouldn’t be able to tell me). The kids said “hi” and “bye” to him in the halls. Hands were held out for high fives. And, when he would flop to the floor or engage in a meltdown, he was given a wide berth without being ostracized.

In his last months there, when his self-injurious behavior, aggression and meltdowns were at their peak, he managed to walk to the stage for his fifth grade graduation on the arm of his father in a scene of serene calm – the most glaring proof to me of God’s existence and merciful answering of my selfish prayers . The fifth graders went wild for him. The teachers and principal shed tears, as I wept in the back of the cafeteria. It’s a moment the assistant principal still speaks to me of a year later.

On the last day of school, when the fifth graders were signing each other’s yearbooks and graduation t-shirts, many of them made a special trip to Lil D’s classroom to sign his yearbook and write on his shirt. “You rock!” “I’m glad we’re friends.” “Have a great summer!” Trite phrases that meant so much to me.

A Mutually Beneficial Relationship

Lil D has been in his private autism school for eight months now, and it’s been the best place for him. They have worked tirelessly to help reduce his self-injurious behaviors, and they have the trained staff to manage him when things get scary. He finally now is able to work on his IEP goals again. He is where he should be. And, make no mistake, I do not want him back in public school, where he was spinning his IEP wheels.

But the social interaction that comes when a public school population embraces their special needs students, well that is worth gold. I know this. My friend (whose daughter is still at Lil D’s old school) knows this as well. It is good for our kids, but it is also good for the other students.

I know Lil D and the other students from his autism class in his public school taught their “neurotypical” peers about acceptance, tolerance, love, care, hard work, support and friendship – lessons I hope they carry into middle school, high school, college and beyond.

There’s a video making the rounds on social media that beautifully highlights what happens when kids embrace and support a special needs student in their class or team. You’ve seen, it, right? I’m talking about the video of Mitchell Marcus, a student manager (with special needs) of the basketball team at Coronado High School in El Paso, Texas, who got his “one moment in time” because of Coach Peter Morales and high school senior Jonathan Montanez – a player on the opposing team.

Watch it here. And teach your children to be accepting and tolerant of others with disabilities. Teach them to be friendly, to stand up for people with special needs, to not be judgmental. Because as hard as special needs kids are working to ease their square peg of a life into this round hole of a world, the world must also learn to live with them in good faith, friendship and support.