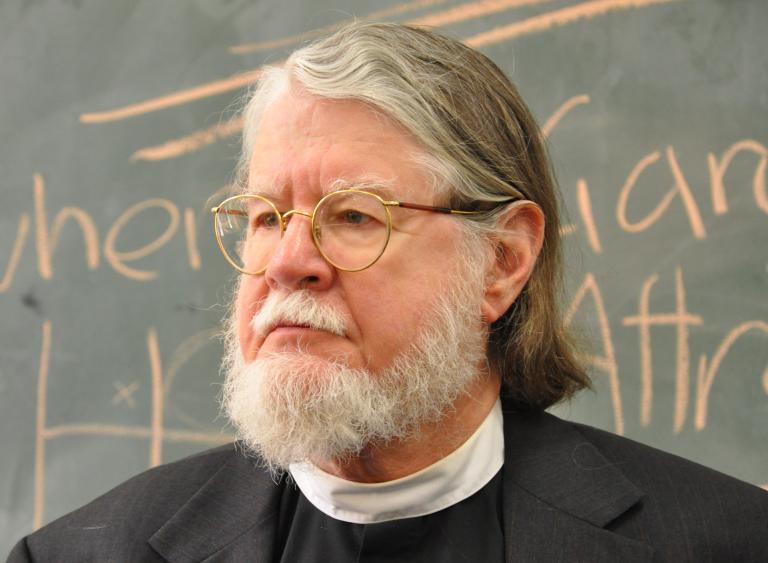

I was not among Robert Jenson’s close friends, but when he died last week I lost a friend and ally.

I was not among Robert Jenson’s close friends, but when he died last week I lost a friend and ally.

For some time, Jenson has been the most influential Lutheran theologian in America. And his influence has crossed denominational lines. Baptist, Presbyterian, Anglican, and even Catholic theologians have rethought the faith—but usually along orthodox lines—because of Jenson’s probing and provocative writings.

Jenson is best known for two areas of exploration—the Trinity and God’s relation to history. He follows the Cappadocians (Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa) in arguing robustly for three distinct Persons in the Trinity—against the recurring Western temptation to modalism (God is one person in three modes of appearance). It is this Trinitarian God who is the true God, and the Trinity is known by seeing its second Person: “Any pattern of thought that in any way abstracts God ‘himself’ from this person, from his death or his career or his birth or his family or his Jewishness or his maleness or his teaching or the particular intercession and rule he as risen now exercises, has, according to Nicea, no place in the church” (Systematic Theology, 103).

Jenson took seriously the Bible’s testimony that this Triune God entered history in the Second Person. He took it so seriously as to suggest that God is constituted by this history, which has led the Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart to charge that Jenson compromised God’s transcendence. Jenson’s response, as I understand him, is to say that God chose to be constituted by history and so remains sovereign over history. Jenson is also well-known for rejecting classical formulations of divine impassibility, the notion that God does not suffer.

I came to know “Jens” personally in two areas of research that we shared—Jonathan Edwards and Israel. His book America’s Theologian (Oxford University Press, 1992) was a breakthrough in Edwards studies. Jenson brought Edwards into dialogue with the “greats” of Christian thought, including Karl Barth and other recent European theologians. This helped establish Edwards as a major theological resource for Christians in this new century. Jenson highlighted Edwards’s aesthetics, helping to show that for Edwards God’s beauty was more integral than for any other Christian thinker. When it first appeared, I was impressed that Jenson included in it a brief but pointed denunciation of abortion on demand.

In the early part of this century Jenson was the Christian leader of a Jewish-Christian dialogue group that I had the privilege of joining. It culminated in two conferences—one at Yale and one in Jerusalem—and a book (Covenant and Hope) that he co-edited with the Jewish theologian Eugene Korn. Jens understood the significance of the Jewish people and Israel’s land more clearly than most. I am deeply grateful for the blurb he wrote for my book Israel Matters.

I will miss Jens and the lovely dinner parties he hosted at his home with his theologian wife Blanche. But I imagine he is reveling in his conversations today with Jonathan Edwards and Maximus the Confessor, two of his favorite theologians.