Many of the deities widely pictured and honored in both Pagandom and society at large have rather nebulous origins. Some of them lack mythology, or perhaps we call them by the wrong name. The Native American Kokopelli is one of those deities we know very little about, it’s likely that his name was not even Kokopelli until relatively recently. He’s a rather beloved deity in my house even if he’s not a frequent guest during ritual.*

Kokopelli The Petroglyph

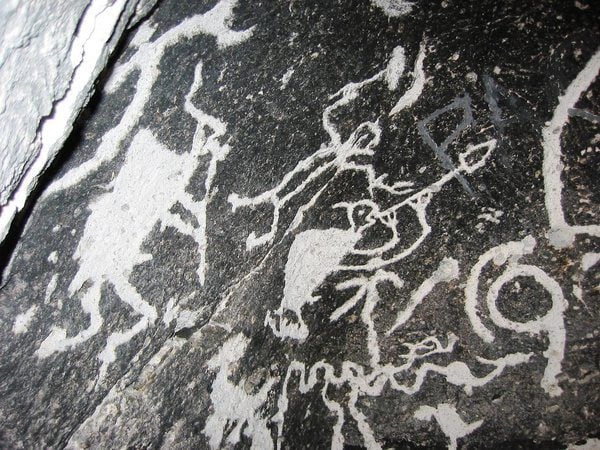

There is a lot of art depicting the character we call Kokopelli, and it can be found as far north as the Canadian Rockies, as far east as Oklahoma, and as far west as California. Though the figure became popular throughout a large chunk of North America, Kokopelli’s origin point is the Four Corners region of the American Southwest (where current-day Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico meet). About 1300 years ago (or earlier, some scholars say he first appeared in the year 200 CE!) a group of Native Americans started making these pictures of what we today think of as a slightly bent over flute playing man, but even that description is argued about.

Once you get away from the Kokopelli at the mall you are left with several varied looking characters, and the representations of these figures aren’t necessarily in the best of shape. The Native Americans didn’t craft a bunch of Kokopelli statues, what they left us were petroglyphs and pictographs. A petroglyph is made by scratching the oxidized surface of a desert rock, removing the dark outer coating to reveal the lighter rock underneath. It’s like scratching out a picture, and as a result the results aren’t all that great. Pictographs look a little better, those are simply pictures painted onto rock, but very few of those have survived.

Scholars can’t agree on one common origin for Kokopelli or even if he’s even playing a flute. Lots of theories have been suggested for the tube coming out of his mouth, from a blowgun, to the more common flute, to the snout of a bug, more specifically a cicada (or locust). If Kokopelli as a locust sounds rather unpalatable, you’ll be happy to know that to some Native American tribes the cicada was a sacred animal.

Desert dwelling Native Americans made gods out of nearly all the animals found in the desert, from the popular coyote to the Spider-woman chanted about in many a Pagan circle. Many of those animals became a human/animal hybrid, and it’s highly probable that Kokopelli is supposed to be a human looking cicada. The theory even clears up the curve in his back, as the cicada has an arched back.

Most of the Kokopelli petroglyphs depict him with other things, most notably animals and plants. One of the plants that’s in nearly every depiction of Kokopelli is maize. This would tend to lend credibility to the argument that Kokopelli was a fertility god, and indeed, some of the petroglyphs that we lump under the name of Kokopelli depict an erect phallic figure. The erection and the maize certainly seem to indicate that he was simply a deity of abundance and fertility, but some scholars aren’t even sure that Kokopelli was a deity.

Modern Hopis simply call many of the Kokopelli petroglyphs Leelenhoya which translates as flute player. To them, the figure on the rocks isn’t a god or even a bug; he’s simply a man playing a flute, enjoying the abundant harvest and the natural world. Scholars have proposed several theories for the origin of the Kokopelli petroglyph that come from the human sphere instead of the insect one.

In many Native American cultures people with physical differences were seen as sacred, or touched by the gods. Someone with Pott’s Disease might have been held in this high regard as well. Instead of being shunned by society (which is a very European way to act) they were welcomed and embraced for what made them different. Hunchbacks in particular were usually thought to have supernatural powers in many Native American cultures, especially in what is today Central Mexico. We know that the people of the American Southwest had made contact with their cousins further south; it stands to reason that some of those traditions were held by both groups of people.

In the 1940’s a group of American scholars tried to trace the origins of Kokopelli back to South America, more specifically to the Callahuayo, a group that lived near present day Bolivia. The Callahuayo were said to be a tribe filled with nomadic, flute playing medicine men who traveled all over the Americas spreading the gifts of music and seed corn. According to this theory, the Kokopelli petroglyph honors these men, the men who perhaps brought corn to the desert Southwest for the first time.

Friends and Neighbors

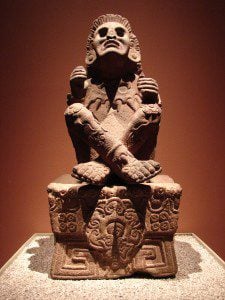

The biggest problem with the theory is that the Aztecs didn’t exist as a distinct civilization until 1250, and pictures of Kokopelli date to at least 700 CE. The two gods are both agriculture and fertility deities, but Xochipilli carries a whole list of attributes that never show up in the Kokopelli petroglyphs.

Xochipilli gets his name from two Aztec words, Xocho which means flowers and Pilli, which translates as prince or small child. He was literally the Flower Prince. He was also known as Macuilxochitl, which means “five flowers.”

In addition to being a fertility god, he was also the god of altered states. Many statues of him dating back to Aztec times show him seated on a throne, surrounded by conscious altering drugs, such as tobacco and hallucinogenic mushrooms. He’s usually shown in a pretty “far out” pose on such statues, suggesting that he’s on some sort of cosmic trip. Scholars use the more respectable term “entheogenic ecstasy” to describe Xochipilli’s state of mind when using such substances. The Aztecs called that mental state temicxoch which translates as the flowery dream. (The next time I consume a bit too much mead at a Dionysus ritual I’m going to tell my friends I’m in the middle of my own flowery dream and see if they buy it.)

About a decade after the theory linking Kokopelli to Xochipilli, a new theory emerged linking our flute player to the Mayan god Ek Chuah. Date-wise it makes much more sense, as the Mayan civilization was already in full swing by the year 700 CE. Ek Chuah and Kokopelli were linked together because of the hump on Kokopelli’s back, a hump that has been interpreted as a sack on a few occasions.

Ek Chuah was generally seen as a traveling salesman in Mayan myth, with a backpack full of goods to trade or give away. His bag always contained some coco beans, and Ek Chuah was known as the god of chocolate. Even today in Mexico there is a chocolate bar named after him with his picture on it. He is often portrayed with what appears to be a droopy lip or a really big nose. The nose might have implied that he sneezed a lot and his name sort of sounds like a sneeze.

I’m skeptical of any link between Kokopelli and Ek Chuah and Xochipilli, but it’s still fun to think about. I will admit to sometimes calling Kokopelli The Flower Prince, a habit picked up after reading about the alleged links between Kokopelli and Xochipilli.

Kokopelli & Kookopölö

The name Kokopelli first appeared in 1898, where it was spelled Kokopeli. Five years later it was spelled Kokopelli, and that spelling has been the most popular ever since. But the term isn’t Native American, it was coined by a white-man. The word that the writer in 1898 was looking for was probably Kookopölö, which is the name of a Hopi kachina who is still worshiped today.

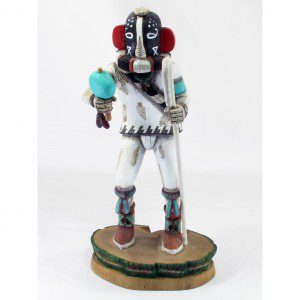

To understand Kookopölö you first have to define the Hopi word “kachina.” To put it simply a kachina is deity or spirit that has the power to influence the natural world. Kachinas are often depicted in doll form (or action figure for us guys); these figures are so common that the term kachina is often just used for the dolls.

Generally the dolls are made out of cottonwood root and decorated with clothes and other objects. Good kachina dolls sometimes retail for hundreds of dollars, and in the last couple of years I’ve seen some Hopi Kookopölö dolls labeled as Kokopelli.

A kachina can also be a man attired in the clothes of a deity while actively invoking it. This is similar to the Pagan tradition of “Drawing Down the Moon,” it’s also found in many contemporary voodoo ceremonies where the loa (spirit) is said to ride (inhabit) the body of the worshiper. In the Hopi tradition only men are allowed to be kachinas.

I think that it’s important to point out that while Kookopölö and Kokopelli share several traits, they don’t exactly look the same. Kookopölö looks much more human and stands a great deal more erect than his petroglyph cousin. He wears a black and white collar around his neck, and has two rather large ears on the side of his head. The cornhusk nose is also prominent. Many depictions of him are phallic, at least the two figures agree on that.

One thing that everyone seems to agree on is that Kookopölö is a phallic deity. The first Kookopölö myth I ever encountered featured the kachina detaching his penis from his body and sending it downstream from where he was bathing to interact with some young ladies. If I remember correctly, he was was successful.

In the beginning Kookopölö was depicted in one way, phallic and naked, and by phallic I mean with a very large erection. Naked deities are common in Native American art; ones with engorged penises are not. The erect penis implies something special, in this case fertility. Sadly though, Kookopölö kachina dolls have lost their phallic edge over the last 100 years due to the influence of repressed whites. Today Kookopölö’s member is kept hidden away.

Not only have the depictions of the kachina dolls changed with the appearance of the white-man, the kachinas who show up in the Native American rituals have started to change too. Kookopölö went from prancing around naked 120 years ago, to then wearing clothes and sometimes flashing his manhood, to now keeping his thing in his pants at nearly all times, at least in public. One Hopi elder described the evolution of Kookopölö in ritual this way:

“People say that in the old days Kookopölö did not cover up his crotch. His penis was there hanging down. But ever since the whites settled here, he does not appear like that anymore. Whenever he wants to come he covers up his loins. Way back he openly showed off his organ. He wore no kilt so that he could have intercourse with a woman without delay . . . .It is really true that Kookopölö used to show his real tail or penis. More recently, whenever he mad an appearance, he wore a penis carved of cottonwood, which was tied to his crotch. Underneath was his real penis, which nowadays he dare not show anymore. This self-made penis too, is no longer seen today. (1)”

While the chances of seeking Kookopölö’s manhood have decreased, he still serves an important function in Hopi religion, acting as an agent of fertility. During ceremonies he tends to grab the ladies and jump around with them, which is supposed to lead towards the woman in question becoming pregnant. Sometimes the ladies approach him during ritual, usually giving him a cornmeal muffin in exchange for his help. There are a few stories of women seeking “serious help” from the kachina and leaving the ceremony with him, what exactly that serious help entails I’ll leave up to you.

Kookopölö often carries a cane or crook staff (shepherd’s crook) in his left hand. Some Hopi’s think the crook staff is used to pull ladies towards him. More commonly in Hopi culture, the crook staff is seen as an “Old Age Marker” and symbolizes longevity. People grab the staff while praying and use it as a talisman to bring themselves a long life free of suffering. It’s also said to represent the many stages of life, from erect youth to the bent shoulders of old age.

Today Kookopölö kachinas are often sold as Kokopelli kachinas completing the circle between the petroglyph and the Hopi deity. As the cult of Kokopelli has spread over the last forty years his image now adorns not just rock art, but coffee houses and pizza parlors. The exact reasons for his newfound popularity have never been adequately explained by scholars, though he’s often linked to the rise of “desert chic.” In the 90’s I remember him at a lot of post-hippy concerts, as people blasted Rusted Root and waited to get into events like Further Fest. Whatever the reason, I’m glad to have him back, he will always be a favorite.

*I don’t like to invoke Native American or Hindu deities into my Wiccan circles, I just think it’s bad form. That being said, Kokopelli and Shiva are still two of my favorite gods.

1. The quote is from Kokopelli: The Making of an Icon by Ekkehart Malotki (University of Nebraska Press, 2000, page 36). Malotki’s book is the go-to source for information about Kokopelli the image and Kookopölö the kachina. Much of this article comes from that book.

2. Malotki page 31.