A Christian Reflects on the Incarnation

By Peter Wehner

As a person of the Christian faith, obviously I find Advent to be a significant time, a time worth reflecting upon. And in reflecting on not just the birth but the life of Jesus, I’m often struck by just how difficult it is for many of us to accept Him on His terms rather than on ours. We’re constantly trying to fit Jesus into our cultural, theological and political boxes. The problem is: He doesn’t really allow for it. As the English poet, playwright and essayist Dorothy Sayers put it:

The people who hanged Christ never, to do them justice, accused him of being a bore—on the contrary, they thought him too dynamic to be safe. It has been left for later generations to muffle up that shattering personality and surround him with an atmosphere of tedium. We have very efficiently pared the claws of the Lion of Judah, certified him “meek and mild,” and recommended him as a fitting household pet for pale curates and pious old ladies.

Sayers is quite right. Jesus stood against the religious authorities of His time; against this holiness code and that legal rule. He was a friend of sinners and at home with the marginalized and those deemed unclean; He was uninterested in worldly power, a critic of the rich, and enemy of the priests. He was thought of as an outlaw, an outcast, and He was rejected by members His own family. As Garry Wills has written, Jesus “walks through social barriers and taboos as if they were cobwebs.”

In His most famous sermon, Jesus told us blessed are the peacemakers, the poor, and the pure in heart; the meek, the merciful, and those who mourn; men and women who hunger and thirst for righteousness and are persecuted for it. Malcolm Muggeridge has written about what he calls the “wonderfully illuminating contradictions” of Jesus – how the first will be the last, the poorest the richest, the weakest the strongest, the most obscure the most celebrated.

Even this condensed and incomplete account of Jesus underscores how silly it is to try to turn Him into a cardboard cutout, a political activist or ideologue, and why He doesn’t fit neatly and comfortably into the doctrinal and denominational categories we create.

But there is something else that needs to be said, which is the staggering idea, at least at the time, of God intervening in human history in order to redirect it, repair it, and redeem it. In this account of things, God is not remote or removed. He has entered into history, into individual lives, and is not indifferent to our fate or untouched by suffering. The God of glory is also the God of wounds. And by His wounds we are healed.

It is quite extraordinary, really; God made Himself part of the human drama. A child born in a manger, in humble surroundings, under questionable circumstances. Yet this became history’s inflection point.

For now, history grinds on, in the words of Philip Yancey, between the time of promise and fulfillment. “We live in a transition time,” he wrote in The Jesus I Never Knew, “a transition from death to life, from human injustice to divine justice, from the old to the new – tragically incomplete yet marked here and there, now and then, with clues of what God will someday achieve in perfection.”

“The reign of God is breaking into the world,” he added, “and we can be its herald.”

*

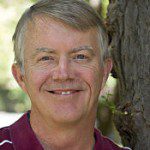

Peter Wehner is a Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He worked previously in the administrations of Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush, where he was deputy assistant to the President. He writes widely on political, cultural, religious, and national-security issues and is coauthor with Michael Gerson of City of Man and with Arthur Brooks of Wealth and Justice

Peter Wehner is a Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He worked previously in the administrations of Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush, where he was deputy assistant to the President. He writes widely on political, cultural, religious, and national-security issues and is coauthor with Michael Gerson of City of Man and with Arthur Brooks of Wealth and Justice