When I was a college sophomore, in the spring of 1995, a wave of student-led events swept across campuses nationwide. Classes were disrupted as fervent gatherings swelled from dozens to hundreds of students and faculty. Songs, speeches, and emotional outpourings lasted through the night. Participants decried failings, individual and corporate, calling for change. The demonstrations spread to more than 100 colleges and attracted national media attention.

It was called a revival.

As commentators have sought to understand the current wave of campus protests against the Israel-Hamas war, they have naturally looked back to Vietnam-era demonstrations and the 1980s campaigns for divestment from South Africa. These are obvious, and instructive, comparisons. Comparing the current protests to the 1995 campus revival is not obvious, but it also is instructive. Religious impulses figure into both sets of demonstrations, but it requires an expansive definition of religion to see them.

The 1995 revival fit squarely within what had come to be the dominant form of American religion since the Reagan years, evangelical Protestantism. The revival began in January with a service of prayer, Bible reading, and confession at Coggin Avenue Baptist Church in Brownwood, Texas. Students at the service carried this momentum back to the “Jesus Parties” at nearby Howard Payne University. Social media did not yet exist, so the revival spread slowly over the next weeks and months, often when a speaker who had participated in one location traveled to another.

The phenomenon hit my campus, Wheaton College, in March, at a Sunday night service where two Howard Payne students spoke. I did not usually attend that service, but I happened to be there that night. I had only evangelical language to describe it at the time—Holy Spirit, confession and repentance, a work of God. Many years later, in graduate school, I would learn about collective effervescence, the term advanced by sociologist Émile Durkheim to describe the special energy that can arise when groups share a powerful, unifying experience. I don’t believe these categories are mutually exclusive. I see them as theological and sociological descriptors that draw different kinds of connections. Invisible threads can link one person to other group members, to the divine, and to co-religionists across time and space. Interpretive threads can also link seemingly disparate mass events, detecting unexpected resonances.

Students in protest encampments now are experiencing collective effervescence. At Columbia University, where this wave began, sophomore Ishaan Barrett wrote in the college newspaper, “Students are protesting through the night, dancing, singing, chanting, laughing, crying, and proving that the most powerful aspect of Columbia has been—and continues to be—its students. … [O]ur togetherness is transformative.” At Northwestern University, according to the Evanston RoundTable, the encampment has been a place where “students and faculty settled into chanting, playing music, hanging signs and working on their laptops.” Graduate student Eden Melles said, “We’re really a village here taking care of each other.” Emerson College junior Jonah Hodari said after a night of encampment, “I didn’t sleep, but many people did. I [had] so much energy that I couldn’t really rest. It was beautiful.”

Student protesters are also calling for repentance, though differently than the calls I heard in 1995. There were some references to collective sins back then (including complacency, apathy, and racism), but the focus was overwhelmingly on individual infractions such as drinking, premarital sex, and listening to “worldly” music. Today, students are deploring genocide, investment in war-related industries, and harsh anti-protest tactics. These are not personal confessions but more like prophetic denunciations, in the “woe to the oppressors” language of biblical passages like Isaiah 10:1–3. It is not necessary to agree with the students’ interpretation of the Israel-Hamas war, nor their prescriptions for what universities ought to do in response, to recognize the pleas as calls to repent. The students are telling their administrators and other American leaders that they are on the wrong path; they need to stop and change direction.

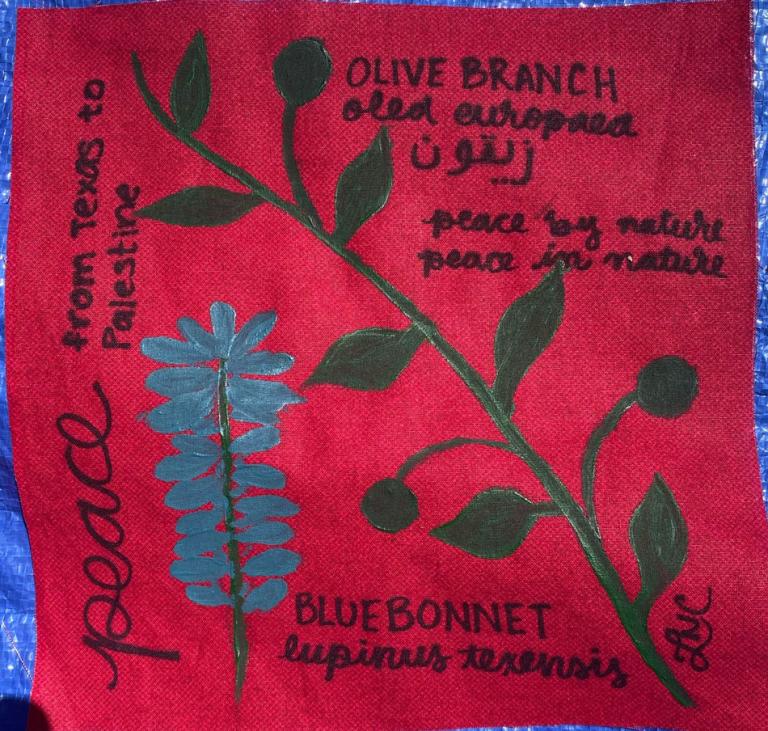

Beyond these specific echoes of 1995, the 2024 student protests are full of religious expressions, predominantly Jewish, Muslim, and Christian. Many, many leaders of the student actions are Jewish, a reality that counters blanket condemnation of the protests as antisemitic. (There have been instances of hate speech at some protests.) “Jewish Students Are Bringing Their Faith to University Pro-Palestine Protests,” reports Teen Vogue, quoting students who have found new meaning in familiar rituals by sharing them with fellow protesters. “I didn’t ever think I’d end up in a position where I’d be as connected as I am with the more religious practices of Judaism,” said one student at Scripps College. Students at Columbia organized both Jewish and Muslim prayers, a pattern repeated at many other encampments. Christian voices have been more muted in these protests, certainly in comparison to the 1995 revivals or even the Vietnam protests, but they are not absent. When Columbia University cracked down on demonstrations, some suspended students found refuge at neighboring Union Theological Seminary. Seminary President Serene Jones told CNN about the Passover seder organized by the displaced protesters:

The service—led by Columbia’s Jewish students—restored for those of us present our sense of community. It was wonderful to see Union’s diverse community of Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist and spiritual but not religious students congregate and share a meal with Columbia’s Jewish students. Together, they held a seder like those happening all over the world. There was prayer. There was quiet contemplation. There was laughter.

Acknowledging the multifaceted tragedies in Israel-Palestine and the United States, Jones insisted, “amidst all of that, people are just looking for a common humanity—a way to stop the pain and make a difference. A way to find solace, together.” Calls for repentance and collective effervescence can combine in new ways, as people bring the resources of faith to bear on enduring human problems.

A pro-Palestinian encampment will not be confused for an evangelical revival. We faced no police in riot gear back in 1995; our vows to be more sober and chaste threatened no one’s election prospects or endowment funds. I probably would never have made the connection, except that my daughter is now a college sophomore—a quirk of personal history tying a spring of praise choruses and guitars to one of protest songs and (at her college) banjos. But if you say “camp meeting” in Protestant circles, what comes to mind is the long tradition of open-air revivals, dating back to the early 1700s. This legacy of religious awakening is one of the relevant contexts for understanding the movement unfolding on college campuses today.

Elesha Coffman is author of the recent Turning Points in American Church History (Baker Academic, 2024), as well as Margaret Mead: A Twentieth-Century Faith (Oxford University Press, 2021) and The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline (Oxford University Press, 2013). Coffman is an Associate Professor of history, specializing in American religious and intellectual history at Baylor University and the editor of Fides et Historia, the journal of the Conference on Faith and History.