“When a Christian rises against a rooted wrong at all,

he is usually an illegitimate Christian,

member of some despised and bastard sect.”

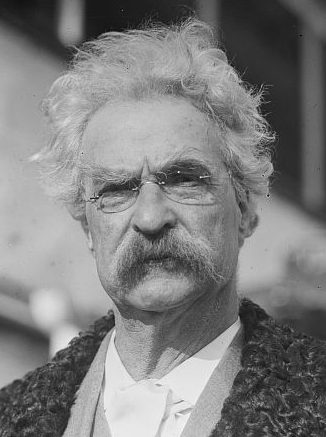

— Mark Twain

Gryphen points us toward a fantastic essay from Mark Twain that I’d not encountered before: “Bible Teaching and Religious Practice.”

This apparently comes from Europe and Elsewhere and A Pen Warmed Up in Hell — two bits of Twain I haven’t yet enjoyed.

I realize that Mark Twain is generally regarded as a critic and foe of both “Bible Teaching” and “Religious Practice” — subjects that, particularly late in his life, made him so grumpy that he almost seems to lose the twinkle in his eye. But Twain isn’t just lobbing spitballs here. This essay seems intended as constructive criticism for Christian Bible-readers, and I think it offers some constructive wisdom for those of us who fit that description.

I realize that Mark Twain is generally regarded as a critic and foe of both “Bible Teaching” and “Religious Practice” — subjects that, particularly late in his life, made him so grumpy that he almost seems to lose the twinkle in his eye. But Twain isn’t just lobbing spitballs here. This essay seems intended as constructive criticism for Christian Bible-readers, and I think it offers some constructive wisdom for those of us who fit that description.

Yes, the essay is full of barbs and plenty of ferocious, sardonic wit. But then Twain is discussing matters such as Sir John Hawkins, founder of the British slave trade — a devout Christian fellow who named his 700-ton slaver The Jesus.

Jesus — nothing less than Mark Twain’s acid pen seems appropriate in response to facts like that.

The entire essay is short, so you should read the whole thing, but here’s a representative taste:

During many ages there were witches. The Bible said so. The Bible commanded that they should not be allowed to live. Therefore the Church, after doing its duty in but a lazy and indolent way for eight hundred years, gathered up its halters, thumbscrews, and firebrands, and set about its holy work in earnest. She worked hard at it night and day during nine centuries and imprisoned, tortured, hanged, and burned whole hordes and armies of witches, and washed the Christian world clean with their foul blood.

Then it was discovered that there was no such thing as witches, and never had been. One does not know whether to laugh or to cry. Who discovered that there was no such thing as a witch — the priest, the parson? No, these never discover anything. At Salem, the parson clung pathetically to his witch text after the laity had abandoned it in remorse and tears for the crimes and cruelties it has persuaded them to do. The parson wanted more blood, more shame, more brutalities; it was the unconsecrated laity that stayed his hand. In Scotland the parson killed the witch after the magistrate had pronounced her innocent; and when the merciful legislature proposed to sweep the hideous laws against witches from the statute book, it was the parson who came imploring, with tears and imprecations, that they be suffered to stand.

There are no witches. The witch text remains; only the practice has changed. Hell fire is gone, but the text remains. Infant damnation is gone, but the text remains. More than two hundred death penalties are gone from the law books, but the texts that authorized them remain.