Question: Who wrote the second epistle to Timothy in the New Testament?

Fundamentalist preacher: Paul.

Biblical scholar: We don’t know, but Paul was long dead by the time it was probably written, so not him.

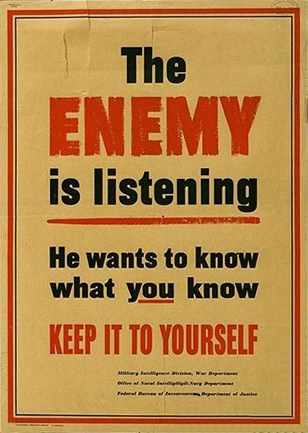

Evangelical pastor: (glances over both shoulders warily, leans in, whispering) Who’s asking?

This is another pernicious aspect to what Peter Enns described as “The Deeper Scandal of the Evangelical Mind: We Are Not Allowed to Use It.” Enns wrote:

Calling for evangelical involvement in public academic discourse is useless if trained evangelicals are legitimately afraid of what will happen to them if they do.

A more basic need is the creation of an evangelical culture where the exercise of the evangelical mind is expected and encouraged.

But, with few exceptions, that culture does not exist. The scandal of the evangelical mind is that degrees, books, papers, and other marks of prestige are valued – provided you come to predetermined conclusions.

I think it’s actually worse than that. The culture of expectation and fear Enns describes doesn’t only require certain predetermined conclusions — reaffirmations of a particular party line. It also requires the pretense of affirming some official, party-line conclusions that most evangelical academics know to be false.

It requires duplicity, forcing us to keep certain uncomfortable truths secret or, even worse, to deny in public some things we know to be true and will acknowledge as true in private.

This is something Karl Giberson and Randall Stephens have addressed in several articles (see this one in The New York Times) and in their book The Anointed: Evangelical Truth in a Secular Age.

But this isn’t just a problem for professional scholars and academics. It affects thousands of evangelicals with undergraduate degrees from mainstream evangelical institutions like Wheaton, Calvin and Gordon. It affects every seminary educated evangelical pastor.

Those folks studied things and learned things. And now they know things. But they also know that much of what they know is not welcome, not accepted, in the wider evangelical subculture. So they have to keep quiet, because if they say in public what they know — what they know to be true — they’ll wind up in trouble with members of their congregation or with donors to their institution or with the evangelical customers of their publishing house.

Who wrote 2 Timothy? How old is the Earth? Does carbon trap heat? Does reparative therapy produce “ex-gays”? Is contraception “abortifacient”?

Evangelical scholars and graduates — including most pastors — know the answers to such questions. But they also know what will likely happen to them if they provide accurate, honest answers to such questions. And they are, as Enns writes, “legitimately afraid of what will happen to them if they do.”

So evangelical scholars and graduates and pastors keep their mouths shut. Evangelical college students learn not to tell their evangelical parents what they’re learning in biology classes, or in geology, or astronomy, or philosophy, or Intro to New Testament. Evangelical pastors develop a knack for dodging or deflecting questions they’re afraid to answer honestly.

This evasiveness and secret-keeping is an integral — or, rather, a dis-integral — part of the education of every educated evangelical. The duplicity is baked right in.

Warren Throckmorton discusses this in a thoughtful response to Enns titled “The Scandal of the Evangelical Double Mind.”

Throckmorton is an interesting guy. He’s a conservative evangelical who teaches psychology at a conservative evangelical college. Yet he’s become known as a troublemaker because he refuses to say what he’s expected to say if he knows it isn’t true.

Throckmorton is best known around the Web for two things: For his patient, thorough criticism of “ex-gay” therapies, and for his stubbornly impatient but just as thorough debunking of David Barton’s bogus “history.”

Throckmorton’s assessment of Barton’s fabrications is no different from that of nearly every other professor at any evangelical college or seminary, or from that of nearly every graduate of any of those evangelical colleges or seminaries. We all know what Throckmorton knows — that Barton is a peddler of flagrant falsehoods. Yet many of us don’t feel free to say so forthrightly for fear of “controversy” or institutional repercussions from Barton’s many supporters in the evangelical subculture.

Barton is an extreme case. He makes such outrageous and outlandish claims that it may seem a bit safer to respond, publicly, by reasserting the facts in response to his fabrications. Thus Throckmorton is not quite as alone and unsupported in his refutation of Barton’s falsehoods as, for example, Katharine Hayhoe is in her courageous refusal to keep silent about the reality of climate science.

Both Throckmorton and Hayhoe demonstrate a candor and an integrity that goes against the grain of our scandalously duplicitous, double-minded subculture. That takes courage, but in the long run it involves less risk than the fear-driven custom of keeping some knowledge secret and giving different answers to different audiences. Such candor will expose you to criticism, to the career-killing label of “controversial,” and to retaliation from the donors who pull the strings at many evangelical institutions. But on the plus side, you won’t have to worry about being exposed as someone who tries to say different things to different people.

The big change and challenge today is this: We have the Internets now. That means such duplicity will be exposed. It’s no longer easy to get away with saying different things to different audiences.

Evangelical scholars and graduates and pastors have kept silent and kept secrets due to being “legitimately afraid of what will happen to them” if they don’t. But keeping secrets may no longer be an option.