Civil disobedience can be a powerful tool for challenging unjust laws. It can be, and sometimes has been, the moral obligation of citizens committed to justice for all.

But not every injustice lends itself to being addressed by civil disobedience. We discussed this here last summer in a post on “Civil disobedience in Hazzard County” — using the old TV show The Dukes of Hazzard as a template for examining situations in which this tool can be extremely effective, and situations in which it tends not to be useful.

Even more importantly, civil disobedience cannot be made to work in defense of injustice.

Even more importantly, civil disobedience cannot be made to work in defense of injustice.

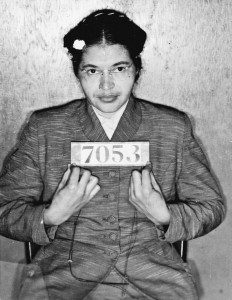

Think of Rosa Parks, one of the great heroes of civil disobedience. The law said that black people had to give up their seats for white people. That was an unjust law, so Rosa Parks broke it. She broke the law and was arrested for breaking the law, forcing the nation to consider whether or not this law was just or right or acceptable. That is what civil disobedience looks like. You break an unjust law and submit to the unjust consequences of arrest and potential conviction and imprisonment for doing so.

An unjust law compelled Rosa Parks to act and she refused to act in compliance with the law. Parks’ action was the first step in a massive, carefully planned and executed nonviolent campaign for justice — one which also involved the powerful economic tool of a boycott. And ultimately, the law was changed.

But what if some modern-day anti-Parks believed that the current equality of desegregated buses presented an injustice needing to be changed back to the old ways of the old days? It’s hard to imagine how civil disobedience would be a useful tool for such an effort. The current law, rewritten to correct the injustice Parks opposed, does not compel this counter-revolutionary to act nor prohibit them from acting. And since it does not directly demand compliance from them, it does not allow them to directly refuse to comply. It does not require their obedience, so it does not allow for their disobedience.

And even if this counter-revolutionary did concoct some elaborate way of disobeying the current law — say by purchasing a bus company, then implementing a policy of segregation on those buses — this tactic still wouldn’t work as “civil disobedience” because the punishment of this violation of the law would not arouse the consciences of others. The punishment of such a violation would be perceived, rightly, as the just enforcement of a just law — as fair and right and good. Our hypothetical counter-revolutionary would be fined or imprisoned and society would nod in assent at this reaffirmation of the law’s essential justice.

Or think all the way back to Henry David Thoreau and his original act of civil disobedience or, as he called it, “Resistance to Civil Government.” Thoreau, like Abraham Lincoln, believed that the U.S. war against Mexico was an unjust, unprovoked land-grab. In opposition to this war, Thoreau practiced and advocated tax resistance — the refusal to pay taxes to the government waging this unjust war.

Thoreau’s tax resistance was far less direct — and therefore far less effective — than Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat. The declaration of war against Mexico did not directly compel Thoreau to act or directly prevent him from acting, and thus it was an unjust law he was incapable of disobeying. He thus chose, instead, to break a different law as an indirect form of protest. That doesn’t work nearly as well and I would argue that it’s not really quite the same as civil disobedience, which I would want to confine to disobedience of the unjust law itself. (This is why much of what is called “civil disobedience” these days is ineffective, since it’s mostly people getting arrested for trespassing when laws against trespassing are not either inherently unjust or the direct subject of the protesters’ complaint.)

But if Thoreau’s elliptically disobedient tax resistance could not and did not stop the war on Mexico, it was at least pointed in the right direction. He was protesting injustice. Can we even imagine what it would have meant if things had been the other way around — if Thoreau had been advocating for an unprovoked war in the absence of any such policy? If that had been his aim, then I cannot think of any way that civil disobedience would have been a useful or necessary tool for him. It cannot be employed to do that. It can be a vital tool for opposition to unjust laws, but it’s an utterly useless tool for those advocating injustice.

America is not a perfectly just society, yet not all of our unjust laws invite or compel a response of civil disobedience. One set of such laws, I think, are the statutes passed by many cities prohibiting the public distribution of food to the homeless. These are laws that require direct obedience and are thus laws that can be directly disobeyed. Such unjust laws are ripe for civil disobedience — preferably for coordinated, well-planned, sustained civil disobedience. I doubt that such statues could survive such a campaign. If these laws were boldly, methodically, publicly and confrontationally broken, then these laws would eventually have to be changed.

Another law that seems to demand a response of civil disobedience is the anti-immigration law in the state of Alabama. Back in 2011, the Center for American Progress listed the “Top 10 Reasons Alabama’s Immigration Law Is a Disaster for Faith Communities.” Among those reasons:

- Religious ministries would be required to ask for documentation from people they serve

- Religious groups would be forbidden to provide rides to worship for undocumented immigrants

- Religious groups would be forbidden to include undocumented immigrants at church dinners

- Religious groups would be forbidden to provide shelter or housing to undocumented immigrants

- Religious groups would be forbidden to perform baptisms or weddings for undocumented immigrants

Religious leaders in Alabama have rightly spoken out against this law. They have written op-eds against it. They have signed petitions. Some have even filed lawsuits or participated in protests in the state capitol. That’s all good and commendable, and they should be proud of that response. But this seems to be an unjust law that is demanding a response of civil disobedience.

Some have used the term “civil disobedience” to describe protests in which opponents of the law have gotten themselves arrested for trespassing in the state capitol. That’s an admirable and courageous act that may help to draw attention to the issue, but it is not civil disobedience — the law against trespassing is not the subject of the protest, nor is it the injustice in question.

The injustice in question is a law that directly prohibits any expression of hospitality or neighborliness to any undocumented non-citizen. That law directly prohibits specific actions and those specific actions can and ought to be performed in direct disobedience to the unjust law.

Civil disobedience clearly applies here. Religious leaders in Alabama ought to continue with their protests, their petitions and op-eds, but they should also oppose this law by:

- Refusing to ask for documentation from people they serve

- Providing rides to worship for undocumented immigrants

- Welcoming and including undocumented immigrants at church dinners

- Providing shelter and housing for undocumented immigrants

- Performing baptisms and weddings for undocumented immigrants

If such civil disobedience were planned, coordinated and sustained with as much strategy, care and dedication as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, then I do not think this unjust law could long survive.

This is, of course, easy for me to say, sitting here in Pennsylvania far-removed from the situation in Alabama. My point here is not to chastise the religious leaders of Alabama for not taking this step, but only to highlight their context as an excellent and obvious example of the enormous potential civil disobedience sometimes has to challenge and to change unjust laws.

And let’s again consider the opposite situation. Imagine you’re a religious leader in a state that does not have a draconian anti-immigrant law like the one in Alabama, but imagine also that for some reason you think it should have such a law — that the lack of legal prohibitions against hospitality and neighborliness seem to you to be an error in the law that you believe needs to be corrected. Civil disobedience simply would be of no use to you in such a campaign. The lack of such a prohibition is not something you would be able to disobey directly. It’s not clear how you could possibly violate the absence of a law directly compelling or prohibiting you from acting. And even if you could devise some scenario in which you might be able to violate such a non-law in some way, your efforts would still not be effective because they would not arouse the consciences of others in agreement with your stand.

In sum, civil disobedience can be an effective and necessary tool for changing unjust laws that require direct obedience. It tends to be far less useful for opposing unjust laws that do not require direct obedience. And it is utterly useless as a tool for promoting injustice.

If you’re wondering what prompted all this on a Monday afternoon, well, all of the above was written in response to the fact that Southern Baptist “ethics” spokesman Richard Land is still a deluded wanker and the that the National Religious Broadcasters conference is a self-absorbed bunch of fantasists who imagine that they’re all Dietrich Bonhoeffer and everyone else is Hitler.