Who said the following? “It’s obvious the majority of the community liked it. So should we deny the 95 percent of those that liked it their rights, just for the 5 percent of people who are upset?”

A. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, referring to his Sunni militia’s seizure of control of majority-Sunni regions in Iraq.

B. Rick Konopasek, member of the Fourth of July Parade Committee of Norfolk, Nebraska, referring to the majority-white support for a racist float in the town’s annual parade.

The correct answer, in this case, was “B.” You can read all about it in Mara Klecker’s report last month for the Lincoln Journal Star.

It would, of course, be foolish to suggest any kind of equivalence between these two things (almost as foolish as attempting a hostile reading of this post that tried to insert some such claim to equivalence here). The Nebraska story is far from harmless, as such ethnic intimidation has very real economic and legal consequences that affect the very real well-being, financial security and physical safety of real people. But it’s still nothing at all like a rampaging guerrilla army carrying out a violent campaign of religious cleansing.

But while we mustn’t equate the two, we do need to appreciate what they have in common and to learn from it, because this Cornhusker committee member has provided us with a clarifying distillation of the logic motivating not just ISIS/ISIL, but every such army waging sectarian violence anywhere in the world: Why should the majority have to respect the rights of the minority?

Wherever that question cannot be answered, there will be oppression and there will be conflict.

The violence of ISIS in Iraq has been described by some here in the U.S. as the “persecution” of Christians. That’s not wholly wrong, but it’s misleading in a way that ultimately feeds into and reinforces sectarian violence. The persecution of Christians in Iraq is, indeed, one effect of the religious cleansing being perpetrated by ISIS, but it is not the only, or even the primary, effect. This is a group that is trying, by force, to create religious hegemony, and for them that means displacing or destroying everyone who doesn’t share their particular sectarian variety of Sunni Islam. Christians and Yazidis are small, relatively powerless minorities in the area and so they are being brutally crushed, slaughtered or swept away, but so are Shiite Muslims and anyone ISIS regards as the wrong kind of Sunni.

Vague appeals to “defend religious freedom” aren’t helpful here because this is precisely what groups like the ISIS militia imagine they’re doing — defending their religious freedom. This is also what both the Seleka and the anti-Balaka militias in the Central African Republic imagine they’re doing. It’s what the Buddhist authorities in Myanmar imagine they are doing by crushing that country’s minority Rohingya population.

This isn’t new — it’s also what Thomas Wyatt and Queen Mary I both imagined they were doing back in 1554. When “religious freedom” and other fundamental human rights are contingent on which faction controls the throne, then factions will fight to control that throne.

Picking sides or defending one side in such a conflict doesn’t alter the overall dynamic and cannot resolve the perpetual cycle of violence. The only thing that can do that is to ensure that religious freedom and other fundamental human rights are not contingent — that they are enshrined in the rule of law, equally, for the majority and the minority alike.

That is also, ultimately, the only way to defend persecuted religious minorities — Iraqi Christians or anyone else.

Many American Christians are rightly horrified by what is happening to Christians in Iraq. In response, as Cathy Lynn Grossman reports for RNS, some have taken to social media to raise awareness about the plight of our brothers and sisters in that country:

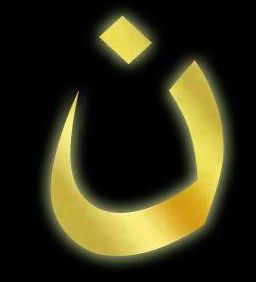

#WeAreN is sweeping the Christian Twittersphere as churches, organizations and individuals change their avatars to the Arabic letter “Nun.”

It’s the symbol for “Nazarene,” or Christian, used by Islamic State militants in Iraq to brand Christian properties in Iraq as part of their effort to drive out an ancient Christian community with threats to convert or die.

That #WeAreN campaign is a good impulse — solidarity with those suffering oppression is always a good thing, as is raising awareness about injustice.

But it’s also a troublingly tribal expression of sectarian solidarity — an expression of support for “our” sect in this sectarian conflict. And that can be a dangerous, destructive thing. Groups like ISIS are likely to perceive this as confirming that we are unwilling to defend the rights and freedoms of their sect, reinforcing their belief that their only avenue is to defend their sect through violence, seizing control of the throne and establishing their religious hegemony to prevent us (or anyone else) from establishing ours.

But it’s also a troublingly tribal expression of sectarian solidarity — an expression of support for “our” sect in this sectarian conflict. And that can be a dangerous, destructive thing. Groups like ISIS are likely to perceive this as confirming that we are unwilling to defend the rights and freedoms of their sect, reinforcing their belief that their only avenue is to defend their sect through violence, seizing control of the throne and establishing their religious hegemony to prevent us (or anyone else) from establishing ours.

I appreciate Michael Brendan Dougherty’s argument that “America is duty bound to help Iraqi Christians.” But Dougherty’s Pottery-Barn argument also applies to Yazidis and, in fact, to Iraqi Sunnis displaced and disenfranchised not just by the American-led war, but by the Shiite regime installed and propped up (until recently) by America.

I commend Kirsten Powers for drawing attention to the humanitarian crisis facing Christians and other religious minorities in Iraq. But Powers blurs the distinction between “us” Americans and “us” Christians, and so her proposed remedies involve taking sides within Iraq’s sectarian conflicts rather than helping to create the only framework that can end them.

Picking sides in a sectarian conflict is not the same thing as defending the persecuted. In the long run, the only way to defend the persecuted is to end the cycle of sectarian violence — which is to say, to eliminate sectarian government and replace it with secular government that protects the rights of religious minorities under law.

The ins and outs of sectarian conflicts can be dizzyingly confusing. Here in America, we struggle to keep track of basic sectarian distinctions like Sunni and Shiite, let alone the esoteric (to outsiders) distinctions within those broad streams, or the the myriad other groups and factions and sects involved — Yazidis, Shakar, Turkmen, Alawites, Druze, Christians, etc. And where do the Kurds fit into all this? Or the Syrian Christians? (Tim F. offered a good overview of the interplay among these factions in Iraq and Syria last month, although it’s already out of date.)

But you don’t need to be an expert in world religion to understand the basic dynamic of sectarian conflict. All you need to know is that it is the inevitable result of any situation in which the 95 percent majority is able to disregard the rights of the 5 percent minority. Or in which the 40 percent plurality is able to disregard the rights of all the smaller factions.

Wherever rights are contingent, there will be conflict. Wherever religious freedom is contingent on which sect controls the sectarian government, there will be sectarian conflict.