There’s one more sentence I want to highlight in Dave Gushee’s column on “When the evangelical establishment comes after you“:

Look at all the pastors I hear from who tell me they would announce their own change of heart if they didn’t have to fear the consequences.

This is an open secret. And it’s why the Eugene Peterson Thing is particularly shameful.

Jonathan Merritt didn’t set a trap for Peterson by asking some tricky gotcha question that backed him into a corner. Here is what Merritt asked, in a public interview arranged by Peterson’s own publicist: “You are Presbyterian, and your denomination has really been grappling with some of the hot-button issues. I think particularly of homosexuality and same-sex marriage. Has your view on that changed over the years?”

That’s a gentle, open-ended, say-only-as-much-as-you-want question. Peterson had every opportunity to state the Required Official Stance he recited later in the formal press release that provided his retraction and obsequious apology. (“I affirm a biblical view of marriage: one man to one woman,” the statement reads. “I affirm a biblical view of everything.” No, really, it says that last bit. That’s not a joke. He really offered such a desperately meaningless plea: “I affirm a biblical view of everything.”)

In Merritt’s report on Peterson’s retraction, he explains why it was he asked that question and offered Peterson the chance to say whatever he might want to say about this subject: “I had spoken with several prominent pastors, authors and theologians who intimated that Peterson had told them privately that he was affirming of same-sex relationships.”

Merritt didn’t bring that up in the interview. He didn’t set and spring some trap: “Here’s what others have said you told them in private, are you willing to say the same thing in public?” That wasn’t the agenda of the piece, which is respectful and almost hagiographic — as far from hostile as it could be.

Matthew Vines discusses Peterson’s history of previous and private statements in an important and generously gracious column for Time magazine, “A Beloved Former Pastor Retracted His Support of Same-Sex Marriage. It Will Harm LGBTQ People More Than He May Know“:

As the executive director of an organization that works to advance LGBTQ inclusion in the church, I’ve been aware of Peterson’s accepting views on same-sex relationships for more than two years. He’s shared them in smaller settings for some time now, including in a recorded dialogue at Western Theological Seminary in 2014, the video of which is now online. I did not publicize those statements then, because I believe in giving people space to decide for themselves how much they are willing to sacrifice to stand in solidarity with LGBTQ people. I hoped he would choose to stand with us in a meaningful way regardless of the cost, but honestly, I didn’t know if he would, because the cost can be very steep.

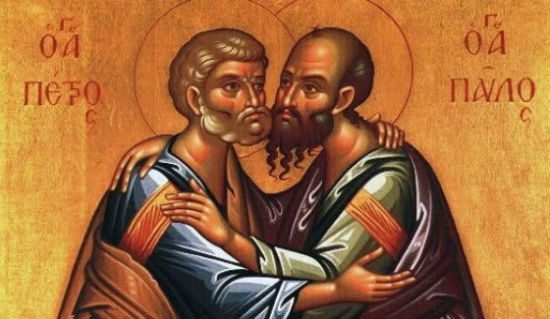

Vines’ essay is more sorrowful than it is angry. His tone is far gentler than the Apostle Paul’s was when he confronted Peter about this very same kind of cowardly duplicity.

We looked at that story in yesterday’s “Sunday favorites” post, but here it is again, from the second chapter of Galatians:

But when Peter came to Antioch, I opposed him to his face, because he stood self-condemned; for until certain people came from James, he used to eat with the Gentiles. But after they came, he drew back and kept himself separate for fear of the circumcision faction. And the other Jewish Christians joined him in this hypocrisy, so that even Barnabas was led astray by their hypocrisy. But when I saw that they were not acting consistently with the truth of the gospel, I said to Peter before them all, “If you, though a Jew, live like a Gentile and not like a Jew, how can you compel the Gentiles to live like Jews?”

Peter “stood self-condemned” because he was behaving one way around one set of people, then turning around and behaving differently around a different set of people. When he was alone in private with the Gentile Christians, he ate with them and affirmed their full membership in the community without any talk of requiring them to get circumcised or to keep kosher. But when the early church’s equivalent of the evangelical gatekeepers showed up — “the circumcision faction” — he abruptly changed, reaffirming the biblical view of diet and the biblical view of circumcision and the biblical view of everything.

And Paul wasn’t having that, because such duplicity and exclusion would harm Gentile Christians more than he may know. He knew that Peter knew better than that. Peter had, after all, personally received a vision from God. “God has shown me that I should not call anyone profane or unclean,” he had said. And yet “he drew back and kept himself separate for fear.” Fear of the “very steep” cost that one may be required to pay “when the establishment comes after you.”

Again, this is Peter we’re talking about here. The Apostle Peter. Saint Peter. Foremost of the original 12 disciples. Lived and worked with Jesus for years. He was the emcee at Pentecost. He healed the lame and cast out demons. He walked on water (briefly, but still). This is upon-this-rock, keeper-of-the-keys Peter doing this.

That’s why his cowardly hypocrisy is so disappointing to Paul and to anyone who reads this story in Galatians. That disappointment doesn’t negate all those other things that are still true about Peter. It doesn’t erase and obliterate every other thing about this great disciple.

It helps, of course, that Peter seems to have corrected himself. There are different ways to place this story into the timeline of the book of Acts, but however that all fits together the end of the story is that Peter got his act together, finding the courage to embrace the Gentile believers in public the same way he had been doing in private.

That restores Peter’s integrity and his reputation, but more importantly for me, personally, it’s also why I’m allowed to be a Christian. If the gatekeepers of the circumcision faction and “the biblical view of everything” had managed to bully Peter and Paul into submission, then Gentiles like myself would be in precisely the same predicament that LGBT Christians are today within evangelicalism.

Take a moment to ponder that and to consider the staggering level of hypocrisy and ingratitude it takes for Gentile Christians to now play the role of that circumcision faction. It really is just the Very Worst. Are we so foolish? Did we experience so much for nothing? Having started with the Spirit, are we now ending with the flesh?

This story from Galatians is important right now as an antidote to some of the general responses I’ve been seeing to the Eugene Peterson Thing. One general form of response has been to defend Peterson’s long, fruitful record as a pastor and as a pastor to pastors. He’s a Good Guy and a nice man and he deserves respect for his long, beneficial work. All true. But I trust it’s not controversial to suggest that all of that is more true of the Apostle Peter than it is of Peterson. If the actual apostle “stood self-condemned,” then it seems odd to presume that any of us, including his namesake, can’t wind up in that same situation.

The story — and the entire book of Galatians — also refutes the second kind of general response I’ve seen to all of this, which is a call for tone-policing and elaborately ceremonial “civility.” Galatians is not a “civil” book. It includes Paul’s suggestion that, since the gatekeepers of the “circumcision faction” are so fond of using sharp objects down there, they should do us all a favor and castrate themselves. The King James Version bowdlerizes this as “I would they were even cut off which trouble you,” but Peterson’s The Message translation does a better job of capturing Paul’s bluntness: “Why don’t these agitators, obsessive as they are about circumcision, go all the way and castrate themselves!”

Note, though, that Peterson’s translation loses something important there about “these agitators” — omitting reference to the victims of their agitation. Paul isn’t upset with the gatekeepers just for the sake of hating on the gatekeepers. He’s angry with them because they’re hurting people. He’s angry on behalf of their victims. He calls out Peter partly for Pete’s sake — to challenge Peter to right himself rather than to stand self-condemned. But mainly he’s concerned with Peter’s hypocrisy because of its effect on others — because it’s harming people more than he may know.

If opposing that harm is “uncivil,” then we all need a bigger dose of incivility.