Be a missionary ev’ry day

Tell the world that Jesus is the wayBe it in the town or country

Or a busy avenue

Africa or Asia

The choice is up to you

The Lord is soon returning

There is no time to lose, so

Be a missionary

God’s own emissary

Be a missionary to-day-ay-ay!

We sang that song in my fundamentalist Sunday school because we loved missionaries. There was no higher calling, no work more deserving of respect and adulation, than being a missionary. Nothing made our church community prouder than seeing a young person* make the declaration that God was calling them to “full-time Christian service,” and that they were heading to Bible college to train to become a missionary.

The two-week annual Missions Conference was the highlight of our liturgical year. The sanctuary would be filled with the flags of every nation in which missionaries sponsored by our church were serving — dozens of them. Folding tables set up in the lobby displayed photographs and cultural symbols from the various missionary families seeking our continued support.

Up on the platform in the sanctuary itself there would be a big thermometer-style graph showing our target budget for missions giving and tracking — in bright red — how close we were coming to this goal in pledges of annual support. This money was a respectable chunk of the church’s annual budget. Giving to support missionaries was a duty, an obligation, and a privilege.

Our church wasn’t unusual in this. The same high regard for mission work, and the same generous level of financial support, is typical of many white evangelical and fundamentalist churches across America. White evangelicals and fundies love missionaries.

During the 1990s, I worked for Ron Sider’s parachurch nonprofit, Evangelicals for Social Action. We weren’t often warmly embraced by our fellow American evangelicals. Like Ron’s most famous book — Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger — we generally were met with a kind of defensive wariness. Sometimes with an outright hostile wariness. “Controversial” was one of the nicer words that was used to describe our call for greater evangelical commitment to temporal justice and assistance to the poor and powerless.

One way I often tried to address this wariness was by pointing out to my evangelical friends that they were already actively supporting the very kinds of “social action” we were talking about. This is what their beloved missionaries were doing. They were running hospitals and schools, digging wells, and looking after orphans and widows in their distress. White evangelicals celebrated all of that when it was being done by missionaries over there, but it seemed disturbing or frightening when we suggested they might do more of the same kind of thing over here.

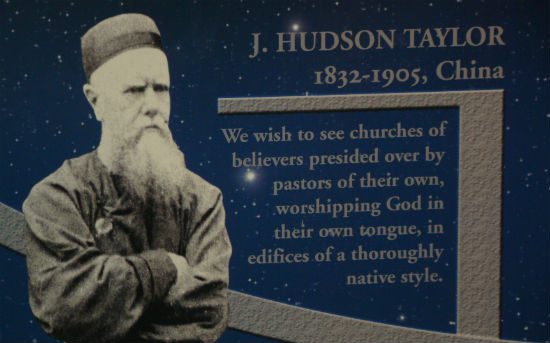

Evangelical missiology has come a long way. It might have taken evangelicals a century or so to learn what people like Hudson Taylor figured out about decolonizing “cross-cultural ministry,” but even some of the most established and well-respected evangelical mission agencies now have a fairly sophisticated understanding of their role as non-colonial, culturally appropriate supporters of indigenous Christianity in any given “mission field.” They tend to be judiciously careful in describing this when back home on furlough, sometimes wincing a bit as they participate in the Mission Conference circuit, but many of them genuinely get it. (Not all, alas — it’s not hard to find examples of 19th-century colonial missiology still being practiced by white-saviors based in “mission compounds” throughout the developing world that still look like some kind of cross between Kingsolver and Kipling.)

There’s a culture gap and a knowledge gap between actual missionaries and the white evangelical congregations that support them. It’s similar to the “faculty lounge” problem I’ve discussed before and to a story I’ve previously mentioned involving a massive American evangelical relief and development agency. Like most relief groups, that agency wants to keep overhead and administrative costs as low as possible. They want the overwhelming share of their budget to support actual aid and development, rather than to support the fundraising that supports that work. They want their fundraising to be as efficient and cost-effective as it can be.

So this group brought in some consultants to study the various components of their fundraising letters to figure out what kind of appeals worked and what didn’t. Those consultants, depressingly, found that the most effective photographs — the ones most likely to inspire white evangelical Americans to respond by writing large checks — involved benevolent looking middle-aged white male executive types surrounded by smiling black and brown children. This was unwelcome information. The agency was theologically committed to a non-colonial, non-evil missiology that meant photos like that were something they were compelled to avoid. They knew that using such photos communicated a host of anti-gospel, anti-Pentecost messages that did real harm to the very people they were striving to serve and that ultimately undermined the work they were doing and their future prospects for continuing and expanding it. But avoiding such pictures would also make it harder to raise funds efficiently.

The culture gap and knowledge gap between the actual missionaries and the congregations supporting them raises a lot of uncomfortable, difficult challenges like that.

I’m not sure “culture gap” or “knowledge gap” adequately describes the gulf here. A more direct and more accurate way of putting it might be to say that the missionaries being supported by white evangelicals are no longer, themselves, white evangelicals. They of course retain the whiteness of their ethnicity, but that whiteness no longer shapes and determines their theology. Taking “cross-cultural ministry” seriously has forced them to interrogate the cultural trappings of their prior understanding of the gospel, of ministry, of hermeneutics. They’ve started following a Jesus who isn’t the White Jesus of white evangelicalism. This runs far deeper than Hudson Taylor’s ponytail. Missionaries have, in a very real sense, converted to a different religion from that of the churches supporting their work.

This religious gap between evangelical Christian missionaries and white evangelicalism has been semi-manageable mainly because those missionaries are far away. White evangelicals here in America aren’t looking over their shoulders or listening in as they work as ministers of a faith no longer shaped in service of whiteness. But this problem becomes much more acute when the “mission field” in question is closer to home.

This is why it’s not at all surprising that the flashpoint for the white evangelical/white fundie backlash against alleged creeping “liberalism” at Moody Bible Institute is focused on a professor in the school’s “Urban Ministries Program.” Urban ministry, in this context, essentially means serving as missionaries to American cities.

Granted, this framework is immensely problematic. It is, in fact, an inadvertent confession that cities and those who dwell in them are presumed to be “foreign” to white evangelicals. It is an admission that white evangelicalism is white and suburban, segregated by geography and class and ethnicity from “urban” people.

Scroll back up and look again at that quote from Hudson Taylor — a 19th-century missionary to China who is today regarded as a kind of evangelical saint. Taylor’s story is told in dozens of hagiographic white evangelical books (and even a not-terrible 1981 biopic from Ken Anderson Films). Taylor’s standing as a white evangelical hero is unchallenged — hence the meme-ification of his quotes on websites from groups run by people who sing “Be a Missionary Every Day” in their Sunday schools.

But think of what Taylor’s admonition means in the context of the “Urban Ministry” mission field: “We wish to see churches of believers presided over by pastors of their own, worshipping God in their own tongue, in edifices of a thoroughly native style.” That entails a surrender of control — “presided over.” This surrender of control is almost tolerable when it involves Chinese believers in the 1800s, but it’s terrifying to suburban white evangelicals when it involves non-white Christians in 21st century American cities.

“Urban ministry” professors advocate for this surrender of top-down control. Their missiology suggests that white evangelicals need to listen to and to learn from pastors and believers who aren’t themselves white evangelicals. It suggests they have things to teach us about liberating the gospel from our own cultural constructs, things to teach us about what the Bible says and means — things we have been unable and unwilling to see because of our ingrained insistence on treating it as a white book about White Jesus.

It’s not surprising that white evangelicals would see all of that as an existential challenge to white evangelicalism, because that’s what it is. Anybody who wants to defend white evangelicalism from this threat can’t be satisfied with a witch-hunt aiming to fire any one professor of urban ministry. They’ll have to fire all of the professors of urban ministry, and all of the international missionaries, and shutter all of those departments and mission agencies. They’ll have to abandon all attempts to engage in or understand “cross-cultural ministry,” and re-establish the unshakeable foundation of English-only suburban inerrancy, just as White Jesus taught.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* It was best if it was someone else’s kid, though, since missionaries — while unquestionably admirable in the abstract — tended to live hat-in-hand, perpetually begging for funding so that they could return to some dangerous, undeveloped foreign backwater. There was no higher calling, certainly, but that wasn’t quite what anyone imagined or hoped for as the context for the raising of their own grandchildren. So it was cause for celebration when other peoples’ kids decided to become missionaries while one’s own kids went off to college to prepare for the kind of lucrative career and secure financial future that would enable them later in life to generously support those poor bastards working as missionaries over in, like, Africa or wherever.