“There is a notion, popular especially in Hollywood, that people who watch things on the Internet have no attention span. This is, of course, nonsense. People are people. They’ll watch something as long as it engages them. That’s all that matters.” — From my ongoing conversation with Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik, creator and writer of The Booth at the End.

Joseph Susanka: For many, the notion of intentionally limiting oneself to a central character and a single location feels impossibly (and unnecessarily) restrictive. But your show underscores the fact that such “obstructions” can be a tremendous boon for creativity rather than a drawback. Do you believe these “short-form” shows are the future of TV, or merely supplemental parts of a more traditional approach? And what was your thinking as you set about to create the show’s most memorable character: The Man, whose scenes are never allowed to last beyond two or three minutes — again defying the instinctive sense that “more is better?”

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: I’m a big fan of “obstructions.”

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: I’m a big fan of “obstructions.”

It’s a boring truism, but if you don’t have limitations of some kind in your creative work, you won’t end up with anything. When you’re making a movie you’re not making a novel… so that’s an obstruction right there. A lot of tools and techniques a novelist might use to tell a tale are not available to you. So, now what? Given the fact you’ll be using camera, mics, lighting instruments, props, sets, and actors, how do you tell a compelling story? The inverse is also true: a novel is black markings on a white page—no color, no motion. Completely different than a movie. Given that, how do you tell a story? What sort of story is best in that format?

As for The Booth, the first “obstruction” was coming up with a show so cheap no one could refuse to greenlight it on financial grounds. Honestly, that’s where the show came from. I decided to trust my indiscriminate love of all modes of storytelling — novels, plays, movies, half-hour television, hour television, epic poems, fairy tales, comic books, and so on — and pull from these many different storytelling modes in an effort to build something new.

I knew that words were the cheapest part of any production. If you tell the story cinematically, that starts getting expensive; it’s one set-up after another, telling the story with one picture after another. But if I could point the camera at actors and have them talk with strong situation and circumstance, I could get a lot more story-per-second-per-dollar than in a normal cinematic setup.

* * *

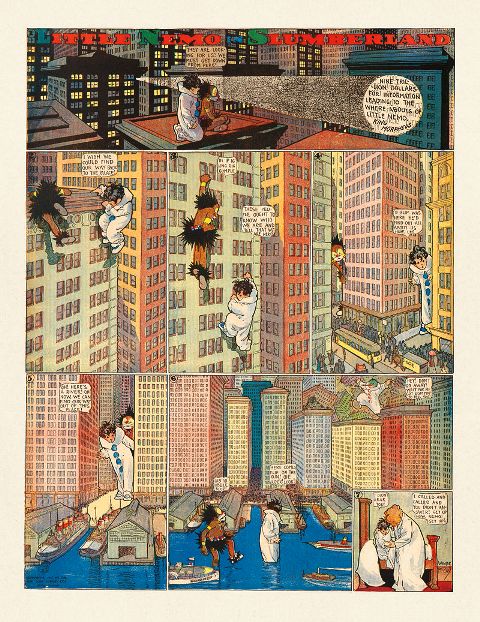

To build the show structurally, I thought in part of Garry Trudeau’s Doonsebury comic strip. If you look at the strips carefully, you’ll see that he “holds” the same image from panel to panel, with only slight adjustments, letting the words carry the weight of the story and comedy. This is in strong contrast, for example, to the work in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo comic strips from the early 1900s, which are all about fantastical imagery and exploiting everything that can be done with imaginative line and color. And yet the Doonesbury strip had run for decades. Moreover, sometimes a day’s four-panel Doonesbury strip was only a small part of a longer story structure that spanned weeks. So, each day Trudeau’s comic strip delivered a self-contained piece of narrative and joke. But it was one beat in a longer narrative.

To build the show structurally, I thought in part of Garry Trudeau’s Doonsebury comic strip. If you look at the strips carefully, you’ll see that he “holds” the same image from panel to panel, with only slight adjustments, letting the words carry the weight of the story and comedy. This is in strong contrast, for example, to the work in Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo comic strips from the early 1900s, which are all about fantastical imagery and exploiting everything that can be done with imaginative line and color. And yet the Doonesbury strip had run for decades. Moreover, sometimes a day’s four-panel Doonesbury strip was only a small part of a longer story structure that spanned weeks. So, each day Trudeau’s comic strip delivered a self-contained piece of narrative and joke. But it was one beat in a longer narrative.

I thought — keeping the two points above in mind — that I could have a simple set (as Trudeau’s panels consist of one simple set, panel after panel on a given day) and have tight scenes that delivered a solid narrative beat (something more complete than the standard screenplay scene), yet still formed a stronger whole once you ran them all together.

* * *

But, of course, I wasn’t building a comic strip. So I fished around in my memory fir shows and plays and movies that I’ve liked that have successfully depended on dialogue and actors and worked within a confined set.

I remembered all the fantastic work from Homicide: Life on the Street and Law & Order in the interrogation room scenes, with the cops try to elicit confessions and the suspects trying to get away with murder.

The interrogation scene is, of course, dramatic narrative boiled to its essence. Anyone who doesn’t understand this doesn’t understand dramatic narrative. As David Mamet noted in his infamous memo:

QUESTION: WHAT IS DRAMA?

DRAMA, AGAIN, IS THE QUEST OF THE HERO TO OVERCOME THOSE THINGS WHICH PREVENT HIM FROM ACHIEVING A SPECIFIC, ACUTE GOAL.

SO: WE, THE WRITERS, MUST ASK OURSELVES OF EVERY SCENE THESE THREE QUESTIONS.

1) WHO WANTS WHAT?

2) WHAT HAPPENS IF HER DON’T GET IT?

3) WHY NOW?

THE ANSWERS TO THESE QUESTIONS ARE LITMUS PAPER. APPLY THEM, AND THEIR ANSWER WILL TELL YOU IF THE SCENE IS DRAMATIC OR NOT.

(The whole memo is written in caps. You can read it here.)

I knew if I could fulfill these craft elements in an economically viable show then I’d have something that worked, even if the show was very simple in its production.

* * *

Two other design elements were very important to me, and I wrote them at the top of the yellow legal pad I was using:

First, when I began fishing around for a show idea that was so cheap no one could say “No” for financial reasons, I wrote at the top of my pad, “No Slumming.” It could be inexpensive, but it had to be, in its own way, something ambitious and something I’d want to see. A lot of folks in Hollywood, when they think New Media or Internet think “It’s less than TV or Film; our bar is lower; let’s not worry too much about this.” My bar was “What is the most compelling thing I can think of? No cheating, no qualification.”

Second, I wrote on the pad, “What is the biggest story I can think of?”

I was thinking here of works by M. Night Shyamalan (specifically The Sixth Sense, Signs and Unbreakable) which are very intimate in what they show on camera, but have stories, themes, and a world that clearly exist beyond the edges of the frame. I knew I’d be working in a very small geographical space, but that didn’t mean the story (or the implications of the story) had to be small. So, how would I make something very large with only two actors talking?

In time, I thought of Richard Matheson’s fantastic short story, “Button, Button.” In the story, a couple receives a box containing a button. A note says that if they press the button, someone they do not know will die. But they will also receive a large sum of money.

I decided that instead of having the characters deal with an inanimate button I would make the Button a living, breathing person. In this way, I’d have dramatic conflict and have enough craft in play to ensure the scenes would work and not be just talking or exposition.

I began working out the rules for the show. There were many little gears that I came up with and either kept or tossed aside. Here are three examples:

I realized that The Man, like the other characters, needed to be caught up in mystery, uncertainty, and vulnerability. If he knew everything or was all-knowing, he would be inherently undramatic. So, I created The Book—a device that had information that could surprise The Man and give the actor playing the character more tension and a greater range of choices as e reacted to what The Book “said.”

I made the show an anthology series. I wanted to make sure that the show “paid off” each story in some way. The show could sustain all sorts of characters, each with different wants and tasks, and could form a “short story” built around each character.

Finally, and strangely, one of the last things I added was the notion the characters’ stories would interweave and connect.

* * *

As for the show being “short form”—I’m not sure I agree with that. The first season is the length of a feature film divided into five standard television half-hours episodes.

A lot of material on the Internet is designed to be short form—and so succeeds in that length. But I don’t think there’s anything short form about the medium itself. The scenes in The Booth are scenes—each about one to three minutes. String them together and you get a feature film’s length of content. The pacing is abrupt—much more so than television or film. But I think that helps push the scenes forward and keeps the audience engaged, because there is so little fat in the telling.

If you were to play out all the events described in the show, you would end up with about 13 hours of cable television. Does this mean I made a “short form” show? Or did I make a really dense show, with a lot of storytelling compactly told? I know which one I think it is, but I’ll let others make up their own minds.

Finally: There is a notion, popular especially in Hollywood, that people who watch things on the Internet have “no attention span.” This is, of course, nonsense. People are people. They’ll watch something as long as it engages them. That’s all that matters. However, for a variety of reasons (usually studio and network notes) storytelling in television is usually flaccid and padded. I would argue that The Booth gets back to older pace of dramatic narrative that is about moving things along.

Finally: There is a notion, popular especially in Hollywood, that people who watch things on the Internet have “no attention span.” This is, of course, nonsense. People are people. They’ll watch something as long as it engages them. That’s all that matters. However, for a variety of reasons (usually studio and network notes) storytelling in television is usually flaccid and padded. I would argue that The Booth gets back to older pace of dramatic narrative that is about moving things along.

* * *

As for the future, who knows? I don’t mean that flippantly. I mean, really, I don’t know, and I don’t think anyone does. That’s what is exciting about all this.

I do think that storytelling is going to get more competitive.

Once upon a time, there were only three networks and a household had one television and that was it. The content was content designed to offend the fewest people — something any family would feel comfortable having on display, since anyone in the family might walk past someone watching any show. And television was a novelty at the time. Two generations grew up with the magic of having all this content delivered into their homes. Nothing else had ever been like it. You didn’t just watch for the stories. You watched because your home had this magical box called a television and you wanted to use this magic box.

Those days are gone. People expect content to arrive. They want the shows they want and they want them now. While there is still a desire for “least offensive content” on network television, we have a whole generation that knows more about watching dramatic narrative than any other generation that’s ever lived. They want the tales that will step up the game and engage in new ways. And with niche audiences becoming the norm, storytellers will have to step up the game and find a voice and grab that audience.

Parts I and II can be found here and here. And stay tuned for Part IV!

Attribution(s): Publicity images and film stills are the property of Hulu and other respective production studios and distributors, and are intended for editorial use only; images of Mr. Kubasik were provided by C.K. himself; “Little Nemo” by Winsor McCay is licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; “David Mamet” comes from Getty Images, which allows the use of certain images “as long as the photo is not used for commercial purposes (meaning in an advertisement or in any way intended to sell a product, raise money, or promote or endorse something);” “Button, Button” is a product link, courtesy of Amazon.