(Lectionary of April 29, 2018)

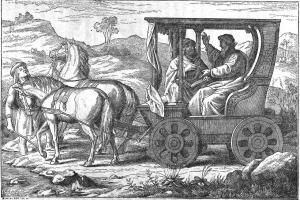

This great story of the Ethiopian eunuch has presented fodder for preachers for two millenia, and its superb telling may lead any homiletician in multiple directions— but, I hasten to add, not multiple directions during one Sunday’s preaching event. The fact that the main subject of the tale is a foreign eunuch, a physical condition expressly denying him access to the Jerusalem Temple, according to clear ancient law, but a law apparently now rejected in the modern Jewish world, suggests that first century Judaism is evolving; he has, after all, just left the worship of the temple before encountering the peripatetic Philip on his way back to Ethiopia. He is clearly a Jewish believer, or at least a Jewish sympathizer, having come from the Temple, and is found reading a portion from the ancient prophet, Isaiah. Thus, neither his physical condition, nor his foreign status, prevents Philip, an early Christian evangelist, from addressing him while running alongside his chariot (!). Nor does it stop Philip from helping him to interpret the Isaianic text by employing the lens of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. It is a clear example of ancient exegesis, or might one better say, eisogesis, shoe-horning a 600-year- old text into a new and contextually distinct world of emerging Christianity.

This great story of the Ethiopian eunuch has presented fodder for preachers for two millenia, and its superb telling may lead any homiletician in multiple directions— but, I hasten to add, not multiple directions during one Sunday’s preaching event. The fact that the main subject of the tale is a foreign eunuch, a physical condition expressly denying him access to the Jerusalem Temple, according to clear ancient law, but a law apparently now rejected in the modern Jewish world, suggests that first century Judaism is evolving; he has, after all, just left the worship of the temple before encountering the peripatetic Philip on his way back to Ethiopia. He is clearly a Jewish believer, or at least a Jewish sympathizer, having come from the Temple, and is found reading a portion from the ancient prophet, Isaiah. Thus, neither his physical condition, nor his foreign status, prevents Philip, an early Christian evangelist, from addressing him while running alongside his chariot (!). Nor does it stop Philip from helping him to interpret the Isaianic text by employing the lens of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. It is a clear example of ancient exegesis, or might one better say, eisogesis, shoe-horning a 600-year- old text into a new and contextually distinct world of emerging Christianity.

Let me say clearly that I am not denigrating the way that Philip leads the eunuch in his reading and application of the Scriptures. It was obviously quite common in early exegesis of the Hebrew Bible to view ancient Hebrew texts through the lens of the life of Jesus, called the Christ by his followers; it still is a very common move, especially among more conservative commentators. And one of the Christians’ favorite books was Isaiah, especially the so-called II-Isaiah, chapters 40-55, that include those famous four Servant Songs, forming a useful framework for the developing notions of who Jesus was and what he had done for his followers. And even more pointedly, Is.52-53 became determinative for the Christian understanding of Jesus’ death on behalf of those who constituted the communities of earliest Christians.

When the eunuch asks guidance for his reading of Isaiah 53:7-8, Phillip immediately “starting with this scripture proclaimed to him the good news about Jesus” (Acts 8:35). Quite obviously, Luke uses this tale as an exemplary one, demonstrating how the ancient text can lead believers to a richer and fuller understanding of the events surrounding the life of Jesus, and how such an understanding can become an entry point into the fresh community of the Christian faith. The eunuch demands baptism as a sign of his desire to join such a community, and Philip obliges at the first body of water. Apparently, proper reading of Scripture and baptism are two crucial demands for joining with the Christians. As the story makes plain, being an Ethiopian, and one who is physically incomplete, is no impediment against entry into Christianity. The tale is a powerful and delightful example of the inclusive nature of Christianity and has served as such for the centuries of Christian evangelism.

Yet, I remain struck, and indeed troubled, by the ways in which the Isaiah passage is used here in Acts. My concern is in the main two-fold: the Isaiah text is summarily torn from its 6th century BCE context of the Israelite exile and is forced to serve a new first- century master. As I said above, this was common practice, and remains common practice, among many Bible readers today. Nevertheless, it is troubling that any text with a relatively clear historical context can be made to say whatever it best serves the commentator to make it say. Even the eunuch points, however unknowingly, to the issue when he asks quite innocently a crucial question: “About whom, may I ask you, does the prophet say this, about himself or about someone else” (Acts 8:34)? That question is still asked by commentators, especially by those who take seriously the exilic context of the passage. Could Isaiah be speaking of himself or of some other historical person or of some historical group from his own time and place? For Philip to jump to the conclusion that it is really Jesus about whom Isaiah speaks is to deny any other possible, and frankly more likely, answer that arises from the context of the composition of the text. Many have thought that the Suffering Servant of Isaiah’s rich imagination could be Israel itself, that nation that has suffered defeat and indignity throughout its long history. But Isaiah has now concluded that Israel’s very suffering might be the way YHWH has chosen to speak to a suffering world, rather than by the traditional means of power. In short, it is Israel’s very weakness that YHWH is now using to teach the world a new way of being and conquering in that world.

This answer bears the advantage of being one that arises from the historical context of the writing and in addition honors the Israelite author who actually reflected on and wrote the passage. Of course, for Luke Christian evangelism trumps historical context, and so it has been for many ever since.

The second concern that arises for me from Luke’s use of the Isaiah text may be found in what is missing from his quotation of Is.53:7-8. He has left out of his quotation the very reason why the Suffering Servant has done what he has done, namely he was “stricken for the transgression of my people” (Is, 53:8b). The whole point of these passages appears to be summed up there; the Servant has suffered on behalf of the people and their sin. Indeed, the early Christian commentators focused squarely on that purpose. More famously, in Is.53:6 we read, “All we like sheep have gone astray; we have all turned to our own way, and YHWH has laid on him the iniquity of us all.” Surely here is the central and crucial rationale for the employment of Is.53 in numerous Christian apologetics both in the early church and in the modern. Yet, that is not seen in Luke’s Isaiah quotation in Acts 8. Rather, Luke appears to focus the eunuch’s and our attention on the denial of justice meted out to the Servant. Indeed, “his life was taken from the earth” because “justice was denied him.” Could it be that Luke has Philip emphasize the injustices surrounding the story of Jesus so as to help the eunuch, himself perhaps a victim of various injustices in his life, identify with this Jesus, a man who suffered such injustices as to be killed? The eunuch is led to baptism not by any conviction that Jesus has “died for his iniquities,” but because Philip has portrayed Jesus as one like the eunuch, a victim of injustice in the world.

Again, the text has been made to play a role that it certainly was not designed to play, and again I say that that is in and of itself no evil thing. However, that same loose way of textual use can become, and has become, a terrible weapon in the hands of commentators whose goal is not to include would-be followers of Jesus, but to exclude those who do not measure up to some sort of preconceived notion of worthiness or rightness. Just ask our LGBTQ friends whether or not biblical texts have been so used. Or African-Americans. Or foreigners. Or any persons that self-proclaimed human judges deem beyond the pale of inclusion in their tightly constructed and restrictive Christian clubs.

Again, the text has been made to play a role that it certainly was not designed to play, and again I say that that is in and of itself no evil thing. However, that same loose way of textual use can become, and has become, a terrible weapon in the hands of commentators whose goal is not to include would-be followers of Jesus, but to exclude those who do not measure up to some sort of preconceived notion of worthiness or rightness. Just ask our LGBTQ friends whether or not biblical texts have been so used. Or African-Americans. Or foreigners. Or any persons that self-proclaimed human judges deem beyond the pale of inclusion in their tightly constructed and restrictive Christian clubs.

The Bible is a wonderful, and at the same time, a terrible book. It has played multiple roles in human history, freeing and liberating, and enslaving and binding. We modern readers must ever be on the lookout for texts, like this one from Acts, that uses other biblical texts in new ways never designed by those earlier texts. They should be for us a warning that the Bible may become a place of darkness and exclusion for some of God’s people. Down that road lies evil and death, denying the love that God in both testaments so desires to bring to the world that God has created.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)