One would be hard-pressed to determine the meaning of Bob Dylan’s song, “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine.” The lyrics are mysterious and haunting. Dylan sings of dreaming about St. Augustine. Which one? St. Augustine of Hippo, the great African theologian and bishop? Augustine the missionary to Britain who became the very first Archbishop of Canterbury? What does the blanket stand for? Why is Augustine wearing a coat of solid gold? Why the reference to there being no martyr among the kings and queens in Dylan’s day? And who are these kings and queens? Who are the souls for whom St. Augustine searches who have already been sold? It’s kind of hard to tell, especially when Dylan’s supposedly recounting a dream (Refer here and here for two attempts at interpreting the song).

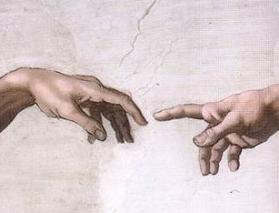

Dylan may not have had Augustine of Hippo in mind, but in my dreaming about Dylan’s song, this Augustine is the one who comes to mind. While St. Augustine of Hippo was no martyr, his excesses almost did him in. His prayer as a youth was “Give me chastity and continence, but not yet.” Raised in affluence and well educated, Augustine lived a life of excess until his conversation to Christianity in his early thirty’s. Upon his conversation, he set upon a long career of writing spiritual, theological and philosophical masterpieces that have reserved him a place as a towering figure in Western thought, not unlike Dylan whose lyrical genius have awarded him a place among the folk and rock musical giants.

Ours is an age of excess. Perhaps the souls that have been sold in Dylan’s day and our own are victims of the rampant commercialism, taken in by Mad Men’s advertising ace Don Draper who sells happiness to customers. Our moralistic therapeutic deistic age pursues happiness,[1] like Augustine did, albeit in drastically different ways, before and after his conversion. In Of the Morals of the Catholic Church, Augustine writes,

How then, according to reason, ought man to live? We all certainly desire to live happily; and there is no human being but assents to this statement almost before it is made. But the title happy cannot, in my opinion, belong either to him who has not what he loves, whatever it may be, or to him who has what he loves if it is hurtful or to him who does not love what he has, although it is good in perfection. For one who seeks what he cannot obtain suffers torture, and one who has got what is not desirable is cheated, and one who does not seek for what is worth seeking for is diseased. Now in all these cases the mind cannot but be unhappy, and happiness and unhappiness cannot reside at the same time in one man; so in none of these cases can the man be happy. I find, then, a fourth case, where the happy life exists,— when that which is man’s chief good is both loved and possessed. For what do we call enjoyment but having at hand the objects of love? And no one can be happy who does not enjoy what is man’s chief good, nor is there any one who enjoys this who is not happy. We must then have at hand our chief good, if we think of living happily.[2]

According to St. Augustine, we all pursue happiness, but in different ways and to different ends. We either torture or cheat ourselves, or are diseased, if we fail to pursue the ultimate Good and see it as the ultimate source of happiness, who for Augustine, is not a Cosmic Therapist and Divine Butler combo of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, but the Trinitarian God of biblical theism, who is the Divine Lover, Beloved and Bond of Love as Father, Son, and Spirit.[3]

I resonate in part with the pursuit of happiness in our day. The question is: what is the happiness that, or who, we seek? Tortured souls, as for Augustine, see the good—ultimately the Triune God. But he laments the fact that they do not possess the Good. Cheated souls are those who think they possess the good but have settled for a lesser good, or even an evil. Diseased souls are those who have the good in their reach but fail to realize what they have to hand. My longing for all of us no matter our age or walk in life, is that we don’t miss out on the ultimate happiness. As with Augustine, so it is truly for all of us: our hearts are restless until they find their rest in God.[4]

In place of “give me chastity and continence, but not yet,” may we say “give me Christ Jesus, even now.”

________________________

[1]According to Christian Smith, “The central goal of life” for the MTD age “is to be happy and to feel good about oneself.” See Christian Smith, “On ‘Moralistic Therapeutic Deism’ as U.S. Teenagers’ Actual, Tacit, De Facto Religious Faith,” page 47: https://www.scribd.com/document/7699752/Moralistic-Therapudic-Deism-by-Christian-Smith

[2]St. Augustine, Of the Morals of the Catholic Church, taken from Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, first series, vol. 4, edited by Philip Schaff; translated by Richard Stothert (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1887), III/4. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight; http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1401.htm; see my blog post on this theme in Augustine: “Blessed Are the Happy in Jesus, not Tortured, Cheated or Diseased Souls;” http://www.patheos.com/blogs/uncommongodcommongood/2015/04/blessed-are-the-happy-in-jesus-not-tortured-cheated-or-diseased-souls/.

[3] St. Augustine, On the Trinity trans. By Edmund Hill (New York: New City Press, 1991) book IX.

[4] St. Augustine, Confessions, trans. By Henry Chadwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), I.i.