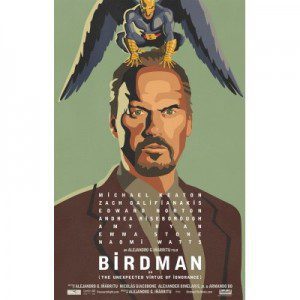

It’s been a week since I saw Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), and I’m still thinking about it. This is a film that sticks with you, like a splinter you just can’t tweeze.

It’s been a week since I saw Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), and I’m still thinking about it. This is a film that sticks with you, like a splinter you just can’t tweeze.

You can check out my Plugged In review to get a rundown of all the movie’s nasty stuff, of course. So with that out of the way, an admission: I liked Birdman. A lot, actually. It’s both utterly real and utterly absurd, filled with dissonance and paradox and just plain weirdness, designed to keep us scratching our chins (or, if we just get impatient with it all, rolling our eyes).

I have a feeling we’re going to be talking more about this come Oscar time, and thankfully, there’s a lot to talk about. But for now, I want to drill down to one of the most spiritually resonant themes in the film: the main character’s sense of relevance.

Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) is a washed-up movie star who flew to fame way back in the 1990s playing a superhero called Birdman (sound at all familiar?). He hung up the bird-cowl and wings after Birdman 3, but it’s still the character that fans still associate with him and, in a way, still want him to be. In an effort to cement himself as an serious actor, he goes to Broadway and produces, directs and stars in a play based on Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.”

It’s an ambitious and incredibly risky move—one that empties his bank account and works on his sanity. And in the rocky days and weeks leading up to the premiere, Riggan battles his own ego and insecurities, which take the disturbingly tangible form of Birdman himself.

The movie is, according to an Entertainment Weekly interview with director Iñárritu, “an exploration of my own ego and how it can become a dictator—how it can elevate you and say, ‘You are the best,’ and then 30 minutes later make you start doubting yourself. For me it was about the everyday fight we all have with mediocrity and the fact that we can’t accept our limitations.”

Riggan can acutely feel his limitations at times. He worries his costar, Mike (Edward Norton) will co-opt his press. He’s weighed down by the theater’s history, the stage of which has been stalked by many a legend.

But Riggan is also constantly told (by Birdman) than he’s better than all these Broadway clowns. He’s a movie star, darn it! He sometimes imagines himself to be almost godlike, levitating off the floor and destroying his dressing room with the gesture of a finger. And there are times when he feels a sense of destiny. When a light conks out a horrible co-star, Riggan believes it was meant to happen—a divine hand in play.

But Riggan is also constantly told (by Birdman) than he’s better than all these Broadway clowns. He’s a movie star, darn it! He sometimes imagines himself to be almost godlike, levitating off the floor and destroying his dressing room with the gesture of a finger. And there are times when he feels a sense of destiny. When a light conks out a horrible co-star, Riggan believes it was meant to happen—a divine hand in play.

His daughter Sam (Emma Stone) is the counterpoint to Riggan’s ego. A recovering drug addict, Sam wiles away her time drawing dashes on rolls of toilet paper—each dash representing a thousand years of the earth’s existence. Just 150 dashes—a few squares worth—sum up all of humanity’s history. It’s a visual summation of insignificance: Everything we’ve ever been and everything we’ve ever done on something you flush down the toilet.

“Let’s face it, dad,” she says. “You’re not doing this for the sake of art! You are doing this because you want to feel relevant again! Well, guess what? There’s an entire world out there where people fight to be relevant every single day! And you act like it doesn’t exist!”

“You are scared to death, like the rest of us, that you don’t matter!” She says.

She’s right. All of us wonder whether we matter sometimes—just as there are times when we think we’re the only thing that matters.

And to me, one of the core beauties of Christian faith is its ability to tie those two paradoxical inclinations of ours into an even greater paradox—to balance the idea with “you’re special” with “you’re not all that” and make it something beautifully profound.

As Christians, we’re taught that we’re incredibly important. We’re made in God’s image, we’re told. We’re beloved by the universe’s most powerful being. And God knows us by name. We’ve been told that so many times that it’s hard for us to grasp anymore. The only thing I can equate it to would be if the most popular girl in junior high ran across the school cafeteria to hug me—my awkward, pimply, braces-wearing me—and invite me to sit with her. Only multiply that by about a gazillion.

And yet we’re asked to set that aside and deflect glory and honor to others. “For Everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted,” we’re told in Luke 14:11. Paul tells us in Colossians to wrap ourselves in “compassionate hearts, kindness and humility.” That line is all about how we interact with others—how to give of ourselves. There’s not a lot in the Bible, I don’t think, about stroking our own egos.

And yet we’re asked to set that aside and deflect glory and honor to others. “For Everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted,” we’re told in Luke 14:11. Paul tells us in Colossians to wrap ourselves in “compassionate hearts, kindness and humility.” That line is all about how we interact with others—how to give of ourselves. There’s not a lot in the Bible, I don’t think, about stroking our own egos.

It’s telling that almost without exception, God uses the humble to fulfill His designs. Maybe they stutter, or they’re poor, or they’re afterthoughts in their own family. They come from humble backgrounds and often have (let’s be honest) humble talent. And yet in spite or because of their limitations, these people become conduits for some pretty amazing things.

Some of us deal with that paradox better than others, but none of us do it perfectly. I’m way more like Riggan than the Apostle Paul, I think. I swing from delusions of grandeur to crippling anxiety. Birdman stalks me, too—telling me I’m great or I suck. But the focus always seems to be about me.

Birdman’s finale is stunningly, maddeningly ambiguous. Did he find a sense of peace? A way to hold that paradox in check? I’d like to think so. And I hope that, as my faith (and understanding of that faith) grows day by day, My own personal Birdman will keep his trap shut a little more often.