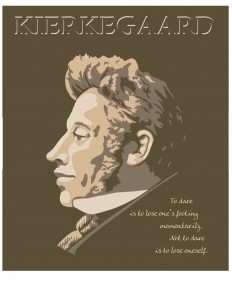

Today is the birthday of the Danish Christian philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard (May 5, 1813 to – November, 11 1855). Among those who have heard of him at all, he is known for such classic works as Fear and Trembling and Sickness Unto Death.

Over his troubled life Kierkegaard stayed true to his faith, but wrestled incessantly with its most visceral implications. As a result of this torment, he died prematurely, exhausted from the test. He was depressed. His unstable childhood ill-prepared him for the greater challenges of life. He fell in love and was engaged to be married to a woman whose love he proclaimed to the end of his days. Yet, for reasons hard to understand, he called off the engagement and never recovered.

I studied Fear and Trembling in college and never forgot its haunting echo. Writing under the name of Johannes de silentio, he says in the preface: “The present author is no philosopher, he is a poetice et eleganter — a freelancer who neither writes the System nor makes any promises about it, who pledges neither anything about the System nor himself to it.” He is making the distinction between heart-felt belief and conventional systematic religiosity as manifested in the Church of Denmark.

The translator and author of the Introduction of the volume I refer to, Alastair Hannay, explains that “the most embracing general message of Fear and Trembling seems to be that faith, [in its] current discussion, is so far cheapened that what is talked about is not properly called faith at all; and that if we are to praise venerable figures like Abraham . . . as the father of faith, we should be made to appreciate what it was like to be Abraham undergoing the trial of faith.” He is referring to the test of faith required of Abraham when God told him to take his only son, Isaac, and go to the mountain and sacrifice him (Genesis 22). Hannay quotes Bob Dylan, who helps the reader grasp Abraham’s dilemma (and Kierkegaard’s): “God said to Abraham, go kill me a son. Abe said, Man, you must be puttin’ me on” (Highway 61).

Kierkegaard wrote:

“Who gave strength to Abraham’s arm, who kept his right arm raised so that it did not fall helplessly down! Anyone who saw this would be paralyzed. What gave strength to Abraham’s soul, so that his eye did not become too clouded to see either Isaac or the ram! Anyone who saw this would become blind. And yet rare enough though they may be, those who are both paralyzed and blind, still more rare is he who can tell the story and give it its due.”

Remembering Kierkegaard –who felt convinced he would be forgotten with the ages–causes me to hope that all that was lost to him in life has somehow been restored in his eternal rest. After having lived a life of faith and having suffered, having wrestled with the most elemental issues that shape human souls, he hung on and stayed true to his belief, though it confounded and crushed him.

We need the courage of a Kierkegaard in these chaotic days. We need believers who will go the hard way with God, as Abraham did; and people who will keep believing, as Kierkegaard did, though he never saw the ram in the thicket.