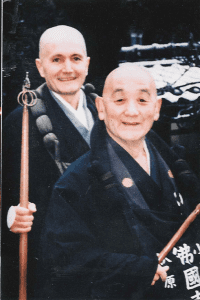

I just found this old photo of Tangen Harada Roshi, the last living successor to Daiun Harada Roshi, in the foreground, and my old friend, Jiku-san, in the background with the ring staff. I remember the morning it was taken during the winter of 1991. I was practicing as a Zen monk at Bukkokuji in Obama, Japan, and it was a day for takuhatsu (托鉢 “begging” or more literally, “holding up the alms bowl”).

A heavy, wet snow had begun to fall as we assembled for 4:00am morning zazen. By the time breakfast was over and it was time to suit up for takuhatsu, we had a good six inches of snow. I’d been in Japan long enough to know that the snow would not be a deciding factor in whether we put on our cotton tabi (足袋, “socks” or more literally, “foot pouch”), tied on our straw sandals (草鞋, “straw sandals” or more literally, “straw sandals”), hoisted up our robes, placed our bamboo rain hats (笠) on our shaved heads, etc., and walked from house-to-house chanting “HO” (法, “dharma”), making ourselves available for alms.

The only thing that mattered was if it was the appointed day. And it was the appointed day. We would be going on takuhatsu.

Our neighboring monastery allowed their monks to wear nice white rubber boots in such inclement conditions. But not us. We were the real cloth-and-straw-in-cold-wet-snow deal. So suit-up we did and off into the wet snow we went, chanting “HO” with enthusiasm. It didn’t take long before my tabi were soaked through and my feet were numb. I assumed my fellow monks’ feet were also numb, but we didn’t stop to chat about it – just “HO.”

Nevertheless, the morning was radiantly beautiful as we moved from house to house with robes flapping in snow and wind. After the initial shock from the harsh conditions, I felt blissed and blessed, experiencing being together with sangha, the community filling our begging bowls with yen and our pouches with rice. After an hour or two, we came back around to the monastery, dressed down into our monk-casual clothes, and sat together in the (unheated) dining hall, gently rubbing our frozen feet until they thawed. It amazed me that no harm seemed to have been done.

Then the neighbor ladies came up to the monastery and made us a special lunch – soup with real bread rolls (a rarity at the time in Japan) and coffee, a meal especially for the Western monks.

I learned something important that morning.

Although we didn’t do it for any particular effect, we monks just choicelessly followed the schedule rather than our fleeting and fickle feelings, the faith of the surrounding community was strengthened. We would have done exactly the same thing even if everybody in the neighborhood had stayed inside and not come out into the winter wonderland, several with tears rolling down their cheeks as they seized the opportunity to give. Well, without the postscript of soup, rolls, and coffee.

I think we all – homeleavers and householders – could feel that an ancient reciprocity had been actualized. We homeleavers could see it in the eyes of the neighbor ladies. The householders could see it in the presence of the monks of Bukkokuji, even the odd foreigners like me, who seemed to be doing this practice without wavering. And they as householders would support us for doing it.

So what?

During the past 50 years in the West, there has been an enormous increase in the number of householder practitioners. Wonderful. The number of practitioners in monasteries has increased just slightly. Not so good. Perhaps the dharma ecosystem is looking for the right balance. Perhaps the monastic way of life is dying.

Yet, in my view, the monastic lifestyle also offers great gifts and it would be a great loss should that way of life be lost. The helpless ones in the future who depend on our practice might just need a developed system of group living based on dharma principles that offers a life of depth and meaning.

This has been on my mind in recent days, because I’ve become aware that there are at least a handful of those with American Soto Zen authorizations who would consider as monastic practice, “ango” (安居, “peaceful dwelling,” intensive periods of monastic practice, click here for more), intensive periods of practice as householders. For some of those who hold this view, training in monasteries is a mark of racial and economic privilege. The argument for the sameness of householder and homeleaver practice seems to go like this: “Isn’t householder practice, if it includes zazen, a teacher’s guidance, study, and liturgy, the same as monastic practice?”

No, in my view, it is not the same. See the definition of “ango” in the link above. I’d add to what’s said there that in monastic practice, we don’t have control of our time, our diet, “our” almost anything. We learn and practice a way of life based on how to actualize the buddhadharma through the twenty-four hours with sangha and in the context of the training center, not a home life with a wide range of personal choices, even when going through a difficult period in life.

Does that mean that the monastic life is better or more important than householder practice, even when the householder’s practice is equally devoted to actualizing the buddhadharma, but in the context of the whirl of modern life, including the sufferings of sexual abuse, or cancer, or the death of a loved one?

No, monastic practice isn’t better than householder practice. In fact, I’d say that the householder life is better suited than monastic life to undergo periods of crisis and grieving as we go through in this rolling, morphing life. And in the course of a life based on practice, many of us will change roles, as if the dharma ecosystem were a game of musical chairs. The fact that all styles of practice, householder and homeleaver, are essentially of one and the same true nature does not obscure the fact that they are different. Indeed, sameness and difference dance in harmony in the same pair of shoes.

As Katagiri Roshi once said, “The sound of chanting and the sound of farting share the same and one nature. And yet, each has it’s own virtuous qualities.”

__________