After a brief hiatus, we return this week to my series discussing interfaith activities as a Pagan. If you’ve missed the earlier articles, part one was an introduction to the topic while in the second part I discussed how organizers often frame an event within a monotheist default and how this can become an opportunity for those that don’t fit the mold. Today, I want to discuss the most common assumptions I face when I engage those unfamiliar with Paganism.

We all make assumptions. It’s impossible not to. Especially when we’re faced with an unfamiliar situation, the only thing we have to work with might be our preconceived notions about how it may be resolved. What’s key in these moments is to understand that our assumptions are flawed; they cannot be universal, i.e. they do not apply to everything or everyone that we find surprising. Despite the fact that we all know this, our assumptions–our stereotypes–persist.

One of the primary reasons that I became involved in interfaith work was to help others examine their assumptions with respect to Paganism. And, especially when I started attending events ten to fifteen years ago, people were largely surprised to learn that Paganism even existed. They were even more surprised to learn that a middle-class American Caucasian cisgender male (i.e. me) could be a Pagan and a polytheist.

To most Americans, Paganism is something that other people do, and by “other people” most Americans mean “people who don’t look like me.” When one of us stands up in a room to introduce ourselves in a way that puts us in opposition to the assumptions others have made, it forces them to perform the sort of re-examination that I always hope I’m able to facilitate.

And, these assumptions are, perhaps, the easiest ones to work on: simply by being present we help to do so. At a workshop at Hartford Seminary, I spent a week with people of many other faiths learning about religious leadership in diverse settings. Twice that week people specifically told me that I had helped expand their horizons with respect to the religious diversity present. One was a Christian religious leader but, more interesting to me, was a Hindu woman who was surprised to meet an American polytheist. In both cases, my attendance was all that was necessary to prompt some deeper thinking about the preconceived notions that we had all probably brought with us to that event.

A harder one to work on is the assumption that humankind has progressed from animism to polytheism onto henotheism before (finally) reaching monotheism. Granted, some would argue that the progression continues passed monotheism (and theism in general) and ends with atheism, but regardless of where it “ends,” this progression feels true; it’s certainly true in other facets of our lives. For example, version one of a software program is typically made obsolete by version two. But, it’s incorrect (and inappropriate) to assume that polytheism was made similarly unnecessary by more recent (Western) theological developments or that our Pagan traditions were trampled by the inevitably marching vanguard of progress.

I was asked once why I practiced a “dead religion.” I was stunned for a moment. How could this person think my religion was “dead” if I was right in front of him claiming to practicing it? I could have accepted an understanding of the relative rarity of our traditions as compared to other religions — that’s easily recognizable as fact. But, he was convinced that to practice a tradition inspired by the cultures of the ancient world was both somewhat ludicrous and, in his mind, regressive.

Typically, it’s not too difficult to convince other interfaith activists that to be different is not the same as to be wrong. It is sometimes harder to convince them that to practice a tradition they consider to be primitive is a worthy pursuit.

Part of that difficulty stems from how deeply embedded the assumption of progress is in our culture. In fact, it’s so deeply embedded that it’s hard not to describe Western civilization without resorting to a chain of events that appears to progress from the primitive to the modern. Consider the steam engine giving way to coal and then internal combustion. And, now, we find that gasoline powered vehicles are beginning to yield to hybrid and fully electric engines.

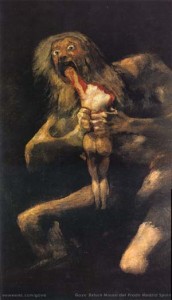

And, at one time, this was the height of our artistic endeavors:

Now we use technology beyond the wildest dreams of our earliest ancestors to create works of such color and complexity that it’s hard to conceive of how the capabilities of the modern world haven’t made obsolescent the actions of the past.

And yet, we consider the cave art at Lascaux, France to be a cultural treasure of great value to all humankind.

When approached by those who have trouble seeing the value of our traditions, sometimes it only takes an example of something in a different context that we continue to treasure to help them see that their assumptions of worth are not as universally applicable as they might have thought. Use my cave art example above, or remind them that it was the Christian monks who recorded the histories of Celtic cultures (biased though these histories may be) regardless of the fact that the Celtic peoples believed vastly differently and, in the point of view of the monks, more primitively. And, there are many examples of things that we can produce (or reproduce) in the modern age that are considered to be of lesser worth than the same or similar objects made with care by hand in the past; the entire antiquing economy relies on such valuations!

In the end, sometimes you won’t be able to get through to people. They’ll find you quaint or simply decide that you’re wrong headedly backward thinking in some of your decisions. But, with luck, those people will be few and far between. In two weeks, I’ll be sharing a few of my thoughts about how I deal with the sometimes unquenchable curiosity that I’ve encountered in others when they have so many questions about Paganism that I’ve been in danger of derailing an otherwise on-topic conversation. Until then, I hope you enjoy other articles here at the Wild Garden, and don’t forget to visit the rest of the Patheos Pagan content.

Images courtesy of shutterstock.com.