It being the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, and Inaguration Day too, I’m taking the liberty to republish a post you may have missed the first time ’round (April 09,2012).

For those of you longing for the days of yore, when the culture was seemingly steeped in Christianity, and all acknowledged it as the one true faith, I’ve got some news for you. Though the faith is alive and well, Christendom is dead and gone. Before you fall all over yourself in consternation, fear and loathing, it’s time to have a look at that word and recall its meaning.

Looking in the handy Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, I find the word defined as follows:

Definition of CHRISTENDOM

1: Christianity

2: the part of the world in which Christianity prevails.

Guess what? Those definitions are weak and worthless, basically. And the reason they fail to define the term is because though #1 gives the simple definition of Christianity as one of the meanings, and #2 points towards a geographical meaning, neither one of these definitions goes to the heart of what is implied when using the term “Christendom.”

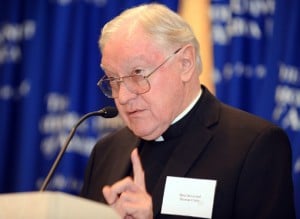

Back in mid-March, I learned of a First Amendment scholar who also happens to be a bishop. You may recall Bishop Thomas J. Curry’s comments regarding how some provisions of the HHS Mandate are not unconstitutional. I noted then that he had written several books on the history of religious freedom in the United States and I quickly logged onto my public library’s website to order them up, pronto. What I share with you here is what I gleaned so far from reading Farewell to Christendom: The Future of Church and State in America,.

I wonder whether the title of his book is descriptive enough, because it gives you the impression that we are only now saying goodbye to an ideal that we have yearned for and lived with for so long. That is why it is important to understand the meaning of the term “Christendom,” you see. Bishop Curry clearly and succintly defines it as, “the system dating from the fourth century by which governments upheld and promoted Christianity.”

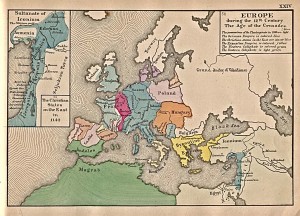

Yes, you can see it all now in your mind’s eye. The full sweep of glorious Christian grandeur from the time when the Roman Emperor Constantine lifted the ban on Christianity and made it the approved state religion of Rome until the fall of the empire. Whereupon the Church stepped into the void of the power vacuum left by the fall of Rome, where she continued as a sort of quasi-government reigning supreme throughout the Middle Ages and seemingly uninterrupted into the Age of Enlightenment.

The truth, though, is far from as rosy as the one painted above. There were plenty of wars, power grabs, and corruption moving along swimmingly throughout the heyday of Christendom. And though I am hard pressed to sum up here all of the history of Christianity in the world between the Edict of Milan and Vatican II (hello, this is a blog post after all), thinking that we are saying farewell to Christendom may give you the idea that we live in some Christian version of a Raymond Chandler novel called Christendom: The Long Goodbye. Because thinking that we are only now moving into the realm of “Post-Christianity” is wrongheaded.

Bishop Curry argues that confusing Christianity with Christendom is wrong because the fact of the matter is, Christendom died right here in America. But not yesterday, not last week, and not even 40 years ago. No siree. Our Founding Fathers put the stake through the heart of Christendom when the Constitution, along with the Bill of Rights, was ratified way back when. If you have to pinpoint an exact date for the obituary of Christendom, see, December 15, 1791 would be a good starting point. Though truthfully, it’s more of an ending point.

If you are trying to wrap your head around the idea that everything you know about the history of religion in America is wrong, that’s because it probably is. Bishop Curry, and I am indebted to his scholarship here, notes in the first chapter of Farewell to Christendom that two great proclamations of the end of Christendom have been written. I’ve told you what the first one is. Care to hazard a guess what the second one is?

This book revolves around two major proclamations of the end of Christendom. The first originated in the Protestant tradition and came by way of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, enacted 1789-1791. The second emerged from the Declaration on Religious Freedom proclaimed in 1965 by the Second vatican Council of the Catholic Church.

I betcha didn’t see that one coming. The problems that the Church, and all churches and religions face in the U.S. nowadays, stem from the problems that Bishop Curry says derive from the misunderstanding of the history of religion in America. The Puritans came to the New World in search of a better Christendom, you see. The experiences of the settlers, and the two dominant approaches that were followed by the them to settle differences among competing Christian denominations, were the experiences that set the stage for the drafting of the First Amendment later on. The ways these differences were settled amount to approaches of 1) religious liberty and 2) religious tolerance.

Bishop Curry writes that “the interpretation of the earlier of these two proclamations, the First Amendment, has reached a point of deep crisis.” And that is because,

Modern Church-State discussion has been based on the following misassumptions: that the free exercise of religion is the equivalent of religious toleration; that members of the First Congress disputed the definition of establishment of religion; that the Free Exercise and No Establishment provisions of the First Amendment serve differing purposes and exist in tension to each other; that the amendment deals with government aid to or hinderance of religion; and that it requires government to maintain a neutral stance between assisting or impeding religion, between religion and nonreligion, and between differing religions.

And guess where the roots of those problems lie?

These misassumptions proceed from a mindset essentially derived from Christendom. Modern attempts to build a wall, to draw a line, to define a boundary between Church and State replicate the perennial struggle of Christendom to separate the secular and the sacred into their proper spheres, even though the First Amendment was designed to end that conflict by proclaiming the end of Christendom in America.

That last bold highlight is mine. Because Bishop Curry shows convincingly by tracing the history of religion in the colonies how the two main approaches on the issue of religious freedom were worked out by the Framers and that the “religious liberty” approach was the one that was decided upon, and not the “religious toleration” approach. The reason why comes down to the idea that the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were written in a manner that limited the powers of the federal government.

If the Framers had decided in favor of the “religious toleration” approach, it is likely that state religions would have been established, as in the model that was followed in Massachusetts, for example. The Framers steered away from those rocks because they did not want the government to have to “maintain a neutral stance between assisting or impeding religion, between religion and nonreligion, and between differing religions.” What they wanted instead was,

a self-limiting, self-denying ordinance restraining government, a mandate that the State will exercise no power in religious questions, that “Congress shall make no law” in that domain of human experience. Religious freedom proceeds from government’s leaving people to decide on their own religious beliefs and practices…

In reality, the First Amendment is about government’s lack of power. It is no more a mandate to promote religion than it is one to create a boundary defining the sphere and activity of religion. Rather, it embodies a new way of arranging government, the full understanding of which is still emerging.

He can say that again.

…the great American experiment still challenges religious believers to realize that the denial of government power over the Church resulted not from deprecation of religious belief, but from a profound appreciation that religion was too important to be left to politicians, too precious and necessary to a vibrant society to be made a tool of government manipulation. The following pages are offered as a guide to that developing understanding and to the realization that the limited, secular, non-ideological government mandated by the Constitution and the First Amendment provides the best hope for Church and State in the new millennium.

Now that is the kind of mandate I can get behind. Which is why our bishops are fighting the HHS Mandate in the manner that they are: as a fight about religious freedom. This may displease those who lament the poor catechesis of the Vatican II generation on the one hand, and the disuse of Church teaching on artificial contraception as outlined in Humane Vitae in America on the other. But those problems are an internal matter for the Church to address. It is not one for the government to decide for us, as they are attempting to do through the HHS Mandate.

I’ll be sharing more from Bishop Curry’s thoughts in future posts.