There are plot spoilers in this review.

I was prepared, based on early returns, not to like Boyhood (★★) as much as everyone else. I wasn’t prepared to dislike it. But I did dislike it. Admitting as much makes one a bit of a lightning rod. My colleague Rebecca Cusey admitted she took some flack for her admittedly minority opinion. NPR’s Kenneth Turan got his own personal rebuttal review from The Chicago Reader. Given how much film critics love attention, you would think the amount lavished on those with negative takes might prompt more nay-sayers to hop on board for their fifteen minutes in the limelight. I’ll try to keep my own comments focused on the film and why I didn’t care for it rather than about me and the fact that I didn’t care for it.

My first disappointment with the film is that nearly everyone in the film is a jerk, nearly all the time. This includes the main character, Mason, his sister, Samantha, both parents (Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette), two step dads, one set of step-grandparents (a shotgun for a graduation present, yay!), nearly every adult teacher or manager, and his peers (bullied in the bathroom, pushed to do drugs and have sex). Possible exceptions include his maternal grandmother and dad’s second wife, though these are more non-entities than positive forces in his life.

There are plenty of good stories or films about jerks, but usually the characters grow or develop over the course of the film, even if they don’t reform. (The example that jumps to mind is The Sopranos, where the lack of any substantive redemption arc doesn’t keep the characters from changing, if in no other ways than in how they fought against their assumed predetermined fate.) I found Boyhood very static regarding its character development. To a certain extent such a project would have to have an unscripted quality to it, but the stop-start element of production appears to have lent itself to more emphasis on continuity than development. That gives the film a deterministic, almost fatalistic air that at three hours could be pretty depressing. Rather than see Mason grow up, we see him deal with the same things (disinterested parents, too much freedom, lack of direction) at each stage of his life.

If you are going to cover a period of nine or ten years in a three hour film, selectivity is a given. The film had an inverse nostalgia, almost as if Linklater insisted on showing only the worst moments. Even when something good is implied–such as when a step-father gives Mason a camera–it happens off-screen, in the gaps and margins. We get the first love after the bloom has started to wear off; we never get any moments of potential, hope, or anticipation. To the extent things are scripted, it feels like we get always the exact wrong impulse acted on at always the most painful moment. The most obvious example is Samantha’s tirade after mom takes the kids out of the house where the drunken step-father beats her and threatens her kids. Is mom just going to leave the step-kids? And why couldn’t Samantha have packed a suitcase or gotten their things? Now her clothes are dirty! Okay, fine, kids are bratty and high school girls can be particularly so. But sometimes kids do sense the brokenness and need in adults and try to respond accordingly. And sometimes even the worst narcissist of a parent does something right. Not here, though. Mom spends Mason’s move out day crying about how her life is slipping away from her and how hurt she is that Mason can’t wait to get away from her. (This even though she’s showed no real interest in or concern for him, even when he admits he has been drinking or she suspects he is doing drugs.) These characters are like pinball machines that bump off each other and circumstances with no real will of their own and no ability to ever touch one another.

Well, what of that? One could argue that such a depressed fatalism is typical of the age group (millenials) and location (non-urban Texas) being depcited. But when I think of Boyhood in comparison to other films or projects that wrestle with some of the same issues, its world view appears particularly bleak. I half-joked coming out of the theater that the characters in Six Feet Under, Alan Ball’s notoriously mopey television show set in a mortuary, appeared to have a greater ability to latch on to moments of happiness in the midst of their miserable lives. Friday Night Lights (film and television show), was able to convey the emotions of feeling stuck, both in childhood and in the middle of nowhere, while acknowledging that adults sometimes care and kids sometimes find channels that don’t lead to dead ends.

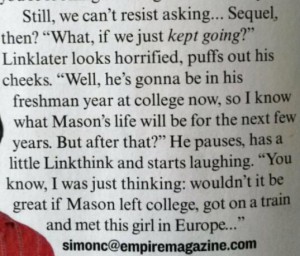

To the right of this paragraph I’ve embedded a quote making its way around Twitter and Facebook in which Linklater floats the idea that Mason grows up to be Jesse from the Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight trilogy? Is this a cute little Easter egg, akin to bringing Picard and Kirk together in a Star Trek movie? As much as I esteemed the Before movies, I found this connection troubling. The first two Before… movies were about choices; they appeared to more equitably balance the characters’ awareness that they are influenced by outside sources with their hopes that they could still make meaningful decisions. I argued in my review of Before Midnight that it felt more fatalistic, but that this was appropriate as the characters were dealing with the consequences of decisions they had made rather than simply trying to decide which path to take. Boyhood, oddly, comes across as even more deterministic despite leaving the character at the point in his life where most people start making their own decisions. Mason appears, for instance, to put more stock in the computer algorithm that pairs roommates than he does in his ability to judge the character and interests of the people he meets. I can’t picture him dropping out of school and taking the train across Europe. He sure appears to believe that–for better or for worse–the die of his life has already been cast and there is not much he can do about it.

To the right of this paragraph I’ve embedded a quote making its way around Twitter and Facebook in which Linklater floats the idea that Mason grows up to be Jesse from the Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight trilogy? Is this a cute little Easter egg, akin to bringing Picard and Kirk together in a Star Trek movie? As much as I esteemed the Before movies, I found this connection troubling. The first two Before… movies were about choices; they appeared to more equitably balance the characters’ awareness that they are influenced by outside sources with their hopes that they could still make meaningful decisions. I argued in my review of Before Midnight that it felt more fatalistic, but that this was appropriate as the characters were dealing with the consequences of decisions they had made rather than simply trying to decide which path to take. Boyhood, oddly, comes across as even more deterministic despite leaving the character at the point in his life where most people start making their own decisions. Mason appears, for instance, to put more stock in the computer algorithm that pairs roommates than he does in his ability to judge the character and interests of the people he meets. I can’t picture him dropping out of school and taking the train across Europe. He sure appears to believe that–for better or for worse–the die of his life has already been cast and there is not much he can do about it.

My wife described Boyhood as “like a Wes Anderson film, but without all the twee.” I can see that, especially since I’m not a huge fan of Anderson’s work and tend to wonder what’s left once you get past the quirkiness. One thing is beauty. Both directors have a keen eye for composition that doesn’t feel forced or staged but still reveals a lot and is often quite beautiful. The beauty of some of the shots in Boyhood is all the more puzzling and infuriating given its mopey content. Why take three hours to tell me there’s no joy or beauty in life and then do it so damn beautifully?