I was just listening to a lecture which I downloaded from The Teaching Company entitled “The Terror of History: Mystics, Heretics, and Witches in the Western Tradition”. (By the way, I love these lectures from The Teaching Company. I’ve purchased over a dozen of them — always when on sale though.)

Anyway, the lecturer, Teofilo F. Ruiz, was speaking about the Waldensian heresy, which was started by Peter Waldo in the 12th century. Waldo was a rich merchant converted to a life of poverty. Eventually, however, the movement was declared a heresy. What was interesting was that Ruiz contrasted Waldo with St. Francis, who was also a (son of a) merchant who converted to a life of poverty. But while Francis was made a saint, Waldo was excommunicated. The difference, according to Ruiz, was that when Francis was ordered not to preach for a period of time, he complied, while Waldo did not. There were other differences between the teachings of the two men, but I thought it was interesting that Ruiz focused on this one distinction. (I just notice that the Wikipedia article on St. Francis also drew this parallel.) Ruiz states earlier in the lecture that the difference between orthodoxy and heresy is power: The one with the most power defines what is orthodoxy.

Back when I was in undergrad, I was required to write a thesis in order to graduate with University Honors. The thesis I chose to write was on a Mormon heresy which occurred a few years earlier in my wife’s hometown. A group which began as an informal and unsanctioned Mormon “study group” eventually broke away from the Mormon church and formed “The True and Living Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints”, or the “TLC” as it was known in the community, when they decided that the Mormon church had itself gone into apostasy. The TLC embrace polygamy (“plural marriage”) and communal property (“the law of consecration”). The significance of these events for a small and mostly orthodox Utah town can hardly be overstated. It tore families apart and divided the community. It also caused those who remained Mormon to draw closer together, which is what I wanted to study.

My thesis did not study the TLC directly, but rather the interpretation of the TLC “apostasy” by Mormons in the community. My theory was that a group’s identity boundaries are threatened when another group, which is different, identifies too closely with them, and this causes the group to try to strengthen its identity by reinforcing the boundaries between the two groups.

I remember when I was on a proselytizing mission in Brazil for the Mormon church how threatened I felt when I met a member of another church — Baha’i, I think — who told me that her church believed, like Mormons, that Joseph Smith was a prophet, and incorporated his teachings into their belief system. I found this much more disturbing than the many other people I met who believed Joseph Smith was a false prophet.

In the minds of the people in the community in Utah, the TLC was not Mormon. But they were also aware that it was very close to Mormonism, too close for comfort, you might say. The TLC obviously grew out of the Mormon experience. All of its members were formerly Mormon. Both the TLC and the LDS Church drew on the same heritage, used the same scriptures and the same religious language, and believed in much of the same doctrine. And while the TLC embraced practices which Mormons no longer condone, those practices were taken from Mormon history. What happens then is the the Mormon community had to figure out (consciously or not) what made them different from the TLC.

I interviewed several members of the Mormon community there who held different positions in the Mormon church. Some were somewhat sympathetic to the TLC, while others were not. I got varying responses to the questions designed to determine where the Mormons drew the line between the LDS church and the TLC. But what they all had in common was a recourse to authority. The one thing they could all agree on was that what distinguished Mormons from the TLC is that the member of the latter disobeyed the Mormon church authority. Everything the TLC members did before leaving the Mormon church could be circumscribed within Mormonism, up until the point that they broke from the authority of the Mormon church.

I had difficulty articulating this conclusion in my thesis, but the realization I had was essentially this: The boundary between orthodoxy and heresy is flexible, and it can be stretch pretty far. But the force that maintains the integrity of that boundary is power, plain and simple, the authority of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. And the role of power in maintaining the integrity of the system increases the larger the scale of the religious organization.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was myself searching for the outlines of what Mormonism is. I wanted to be able to draw a bright line to circumscribe the faith. I realize now that, while any individual can do this for themselves, things necessarily get much fuzzier on the corporate scale. What ultimately holds the religious community together is not shared belief. Even though they may think they share the same beliefs, members of the Mormon church would be surprised to discovery the diversity of belief with the church. I realized this myself only after leaving the church, whereupon I realized that not everyone was a member for the same reasons as was I (my wife for example). This diversity of belief is hidden by the practice of Mormons emphasizing their sameness at all religious gatherings and glossing over differences.

I had difficulty defending my thesis as an undergrad. I think I did not fully understand what I had discovered. One of the chairs of my thesis committee thought I was trying to say that all that Mormons have in common is a shared obedience to the authority of the LDS church authority. But I was not trying to describe the core of Mormon identity. I was trying to describe its boundaries, the circumference of the circle, rather than its center.

One of the people I interviewed was a Mormon church leader who warned me that my studies would lead me out of the church. I was confused and insulted at the time. Of course, he turned out to be right. What I didn’t see at the time was that the very act of searching for the boundaries of the Mormon community put me on the edge of that community; and what I should have been doing as a “good Mormon” was to search for the center.

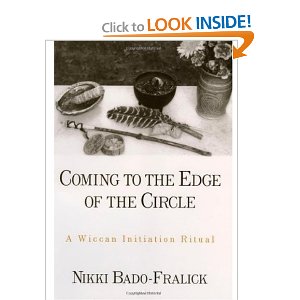

In contrast to the Mormon faith, Paganism seems more interested in boundaries, crossing them as well as maintaining them. The phrases “edge of the circle” is common the Pagan culture: Coming from the Edge of the Circle is the name of a book on Wiccan initiation (the “edge of the circle” being a metaphor for the place of personal transformation); “From the Edge of the Circle” is the name of a Pagan podcast; and “Edge of the Circle” is the name of a Pagan supply store.

Over at the Naturalistic Paganism yahoo group, I picked up a discussion this past June about Pagan identity. B. T. from the Humanistic Paganism website responded as follows:

“With such an individualist religion, I wonder how many ever really identify *with* other Pagans. It seems almost more Pagan to disidentify with Pagans. Frankly, I don’t identify at all with other Pagans’ belief in the efficacy/literal truth of magic, astrology, energy-raising, crystals, and so on. I never feel more out of place than at a Pagan convention. And yet, I continue to be fascinated with these or similar practices, though I interpret them on a metaphorical and psychological level. So personal reservations aside, it still makes sense to call me some kind of Pagan.

“But the struggle with labels is fundamentally a struggle with identity, and that implies a journey of self-discovery, and that journey is the primary energizing factor behind a great deal of Pagan paths. So I guess it’s not so surprising that people can get so much mileage out of the Pagan-or-not debate.”

B. T.’s experience with the larger Pagan community resembles my own very much. His comment made me wonder if perhaps constantly questioning whether we are Pagan is one of the most “Pagan” things we do. This seems to be part of the focus of Paganism on boundaries.