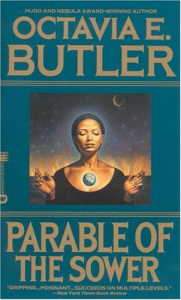

I recently finished reading Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower”. It’s set in the near future when the United States has all but collapsed due to economic pressures. Theft, rape, and murder are the rule. The heroine creates a new religion, which she calls “Earthseed” and which is adopted by a small community of refugees.

The central tenet of Earthseed is: “God is Change. Shape God.”

All that you touch

You Change.

All that you Change

Changes you.

The only lasting truth

Is Change.

God

Is Change.

This premise sounds a lot like Starhawk’s chant:

She changes everything she touches and

everything she touches, changes

Change is, touch is; touch is, change is.

Change us, touch us; touch us, change us.

We are changers;

everything we touch can change.

Butler writes:

Why is the universe?

To shape God.

Why is God?

To shape the universe.

***

God is Change.

God is Infinite,

Irresistible,

Inexorable,

Indifferent.

God is Trickster,

Teacher,

Chaos,

Clay—

God is Change.

Beware:

God exists to shape

And to be shaped.

What’s interesting about this notion of God is not only that God changes us, but also that we can change God — that life is a reciprocal interaction between God and the universe, a notion which I believe was borrowed from process theology.

The fundamental insight of process theology, as I understand it, is that reality is change, motion, flux. Objects, things, moments in time: these are abstractions and unreal. This is true of all reality, including God and ourselves. God is a verb. I am a verb. I am the dancer and God is the Dance.

This God of process theology is not a God to be loved or worshiped. It is a God that is, in Butler’s words, perceived, attended to, learned from, shaped, and ultimately (at death) yielded to:

We do not worship God.

We perceive and attend God.

We learn from God.

With forethought and work,

We shape God.

In the end, we yield to God.

I like that Butler includes “Trickster” in her list of God’s titles, along with “Teacher”. It acknowledges both the malevolent and benevolent, destructive and constructive, sides of God:

As wind,

As water,

As fire,

As life,

God

Is both creative and destructive,

Demanding and yielding,

Scultpor and clay.

God is Infinite Potential:

God is Change.

As Catherine Madsen points out, in discussing the “strange combination of tender bounty and indifference” of this world:

“However certain one may be that one is loved by some presence in the universe–and it is possible, at moments, to be very certain of that–that same presence will kill us all in tun, will visit our lovers with sudden and devastating illness, will freeze our crops, will age our friends, and will never for one moment stand between us and any person who wishes us harm.”

Starhawk describes the Neopagan Goddess as:

“the ever-diversifying creating/destroying/renewing force whose only constant is, as we say, that She Changes Everything She Touches, and Everything she Touches Changes. ‘Nice’ doesn’t seem to be a relevant concept. In some aspects, the Goddess is nurturing and comforting, in others She’s the Sow Who Devours Her Own Young. […]

“The Goddess is not some abstract thought whose qualities we can decide. She is real–meaning that when we call Her in Her various aspects, ‘shit happens,’ as the T-shirt says; the rivers of life-force burst the dams and it’s paddle-or-die. But of course that power is not separate from us; it is the deep stream that runs through the secret heart of each and every cell of our bodies. […]

“Ultimately we don’t decide who or what the Goddess is; we only chose to what depth we will experience our lives.”

In her post-apocalyptic science fiction novel, The Fifth Sacred Thing, Starhawk addresses the issue thusly:

“One of the names of the Goddess was All Possibility, and Madrone wished, for one moment for a more comforting deity, one who would at least claim that only the good possibilities would come to pass.”

“ ‘All means all,’ she heard a voice in her mind whisper. ‘I proliferate, I don’t discriminate. But you have the knife. I spin a billion billion threads, now, cut some and weave with the rest.’ ”

In other words, the Goddess is the force of both preservation and destruction at the heart of nature. If we want to survive, we have to fight for it like the rest of creation. “It’s paddle-or-die,” as Starhawk says. The Goddess does not discriminate, but that does not mean the we should not. As Starhawk writes, “we have the knife” — the power to discriminate. And this power to discriminate gives us the power to shape God, as Butler says.

Last night I was reading the Butler’s sequel, Parable of the Talents, and I came across this text, which is the most thought provoking so far:

Darkness

Gives shape to the light

As light

Shapes the darkness.

Death

Gives shape to life

As life

Shapes death.

The universe

And God

Share this wholeness,

Each

Defining the other.

God

Gives shape to the universe

As the universe

Shapes God.

In the proverb above, Butler uses three quartets, all of which take the following form:

X

Gives shape to Y

As Y

Shapes X.

The X’s are Darkness, Death, and God. The Y’s are Light, Life, and the Universe. It’s interesting that Butler equates God with Darkness and Death. Butler’s God is Chaos. In the Hebrew and Babylonian creation myths, the world begins in darkness and watery chaos, and it is only the discriminating power of light that brings order and life. Theologians Paul Tillich, Meister Eckhart, and Jacob Boehme, all defined God, in part, as an Abyss. I imagine that, when we die, the light of consciousness goes out and we return to chaos, to a less organized state. In other words, we “return to God”.

But what is perhaps even more interesting about Butler’s analogy is not the analogy of God to Darkness and Death, but the analogy of the relationship between God and the Universe to the relationships between darkness and light and death and life. Butler’s proverb suggest that the relationship between God and the Universe is analogous to the relationships between darkness and light and between death and life — in other words, they are complementary opposites. Like Yin and Yang — sharing a “wholeness” and defining each other.

This brings me back to Tillich, who states:

“The divine life is the dynamic unity of depth and form. In mystical language the depth of the divine life, its inexhaustible and ineffable character, is called ’Abyss.’ In philosophical language the form, the meaning and structure element of the divine life, is called ’Logos.’”

Tillich’s Logos is the self-manifestation of God in creation, while the Abyss is the inexhaustible and ineffable source in which all form disappears. When Butler says God and Universe shape and define each other, I imagine that she is talking about God as an inexhaustible Abyss/Source and the Universe as Logos/Form. God is the potentiality which brings change, and the Universe is the actuality which manifests that change. I am just beginning to unpack this idea, but I think it has potential.

The following quote from Butler explains how this concept of God plays out in human life:

A victim of God may,

Through learning adaption,

Become a partner of God.

A victim of God may,

Through forethought and planning,

Become a shaper of God.

Or a victim of God may,

Through shortsightedness and fear,

Remain God’s victim,

God’s plaything,

God’s prey.

To a certain extent, I am victim of forces beyond my control — “God”, if you will. But I do have free will: I can remain a victim, or I can “wield the knife” that is my power of discernment, and become a shaper of God, or of the potentialities that God represents. However, my power to shape my life (to shape “God”) is limited by the finite possibilities that are presented to me. Thus, my life is a product of the reciprocal interplay of “God” shaping me and my shaping “God”.

But why say “God”? Why not say “the World” or “Nature” — because “God” in this sense does mean the world and nature. Here is why I think it is useful to call these things “God”. If I call the world/nature “God”, then I won’t be tempted to (consciously or unconsciously) imagine another (supernatural) agency and call that “God”. “God” is a powerful idea, and if I don’t give a place for that in my life, if I do not find “God” in this world, then I think there is a human tendency to project it outward into the supernatural.

When I say “God is Change”, I am simultaneously denying the claim that God is unchanging and affirming that this world of contingency is all there is. When I say that God can be shaped by us, I am simultaneously denying the claim that God is transcendent and affirming that we have only ourselves to look to for a better future. “God is change — Shape God” is a challenge to see, to learn, and to work to shape our reality, just as we are shaped by it.