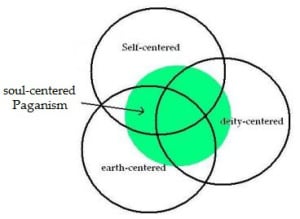

This post is Part 3 of a 3-part series on my evolving sense of Pagan identity. In Part 1 of this series, I admitted to being guilty of a kind of Pagan fundamentalism in my conception of the Pagan community. In Part 2, I envisioned a Pagan community consisting of (at least) three centers with overlapping areas: earth-centered Paganism, Self-centered Paganism (intentionally capitalized), and deity-centered Paganism.

From Self-centered to earth-centered Paganism

“There is a fine old story about a student who came to a rabbi and said, ‘In the olden days there were men who saw the face of God. Why don’t they any more?’ The rabbi replied, ‘Because nowadays no one can stoop so low.'”

— Jung

In their book, Religious and Spiritual Groups in Modern America, Robert Ellwood and Harry Partin identified two of the three “centers” of Paganism discussed in my previous post:

“The unifying theme among the diverse Neo-Pagan traditions is the ecology [1] of one’s relation to nature and [2] to the various parts of one’s self. As Neo-Pagans understand it, the Judaeo-Christian tradition teaches that the human intellectual will is to have dominion [1] over the world, and [2] over the unruly lesser parts of the human psyche, as it, in turn, is to be subordinate to the One God and his will. The Neo-Pagans hold that, on the contrary, we must cooperate with nature and its deep forces on a basis of reverence and exchange. Of the parts of man, the imagination should be first among equals, for man’s true glory is not in what he commands, but in what he sees. What wonders he sees [1] of nature and [2] of himself he leaves untouched, save to glorify and celebrate them. […]

“What Neo-Pagans seek is a new cosmic religion oriented to the tides not of history but [1] of nature — the four directions, the seasons, the path of the sun — and [2] of the timeless configurations of the psyche. […]”

This has continued to be one of the most important descriptions of Paganism for me ever since I first read it. Ellwood and Partin’s book was published in 1973, before the explosion of deity-centered Paganism, and at a time when more deity-centered Heathenry was considered by many (including many Heathens themselves) to be outside the Pagan umbrella. I come back to this quote often because, not only does it identify the two strains of Paganism with which I identify, but it also implies a connection between these two.

My introduction to Paganism was through a Self-centered perspective. (Note: As described in Part 2, “Self” — which is intentionally capitalized — refers to a transpersonal wholeness which transcends, but includes, the ego. Thus, “Self-centeric” is not equivalent to ego-centric.) I saw Paganism as a modern-day mystery religion. One of the things I still appreciate about my religion of origin, Mormonism, is their temple rituals. Unlike Mormons’ aesthetically bland weekly Sunday worship in their multi-purpose meetinghouses, Mormon temple ceremonies are an example of symbolically-rich high ritual. Around the time I left the Mormon church, I came across an article (which I have unfortunately not been able to locate since) which compared LDS temple rituals to the ancient mystery religions. It should then come as no surprise that, years later, my first exposure to Paganism was through an article by Jungian therapist and Wiccan, Vivianne Crowley, “Wicca as a Modern-Day Mystery Religion”.

From the perspective of Self-centered Pagans, like Vivianne Crowley, ritual is designed to facilitate the process of psychological integration and spiritual transformation. As in the ancient mystery religions, this may be accomplished through a symbolic or ritualized death. As Harold Jantz writes in The Mothers in Faust, initiation

“as in all the great mysteries, must first make real to the initiate the meaning of death, total extinction, utter loneliness, and then lead him on, through deep ineffable terror to the mystic glowing hearth of rebirth, of constantly renewed life, of the awareness of his oneness with the totality of life.”

Sometimes this symbolic death is accomplished through “participation” in the mythic death of a fertility deity — but this was about as earthy as my Paganism got in those early years. It seems like a lot of Self-centered Paganism is like that: mainly esoteric in nature, with a romanticized conception of “Nature”, and some eco-friendly practices tacked on almost as an afterthought.

Eventually, though, I came to feel that my ritual experience was missing something. For one thing, I was conducting my rituals shut up indoors with my books. Although my rituals invoked a symbolic nature, I had no real contact with nature in my rituals. So I moved outside, which was a necessary but not sufficient step in the right direction. Around the same time, I read a couple of essays which helped me to realize that my interaction with nature was still superficial: Chas Clifton’s essay “Nature Religion for Real” and Barry Patterson’s essay “Finding your way in the woods“, which is part of his book, The Art of Conversation with the Genius Loci. I gradually came to realize that I needed to connect my Self-centered practice to my burgeoning eco-centered awareness.

Soul-Centered Paganism: Nature and Psyche

“The mystery of the cosmos before which our mind stands in awe becomes one with the mystery within us by which we ethically strive; and both come together in the sense that somehow, in a way inexpressible to us, it is all meaningful.”

— William Barrett

The writings of Carl Jung, James Hillman, Theodore Roszak (who coined the term “eco-psychology”), and wilderness guide Bill Plotkin, have helped me reconcile these two paths — at least theoretically. From these authors, I have developed a conception of nature and psyche which tries to overcome the dualism inherent in traditional understandings of these concepts.

Conceptually, I understand nature and psyche (or soul) as two different perspectives on the same thing. Step one is to propose that “nature” includes not only our physical bodies, but also that thing which we call mind, including consciousness and the unconscious. That is a proposition, I think, that would be easy for most religious naturalists to accept.

Step two is to reverse the principle: Just as nature extends “within” to include the psyche, so psyche extends “without” to include nature. James Hillman describes psyche (soul), not as something inside of us, but as something that we are “inside” of. Psyche extends beyond our individual mind to include other people and all of nature. Hence, Hillman can speak of “a psyche the size of the earth”. “The greater part of the soul lies outside the body” says Hillman (paraphrasing the medieval alchemist and doctor Sendivogius). Now this might seem to violate one of the central tenets of a naturalistic philosophy: that “mind” does not extend to inanimate things. But when I say that psyche extends beyond the individual self, I am not talking about literal animism, but rather about the subjective experience of Nature.

Jung wrote that we need to “reconcile ourselves to the mysterious truth that the spirit is the life of the body seen from within, and the body the outward manifestation of the life of the spirit – the two being really one”. I understand “nature” to be psyche seen from without and “psyche” to be nature seen from within. Thus, “nature” is everything inside and out of me when viewed from an objective perspective, whereas “psyche” is everything inside and outside of me when viewed from a subjective perspective. As Jung wrote:

“The psyche, if you understand it as a phenomenon occurring in living bodies, is a quality of matter, just as our body consists of matter. We discover that this matter has another aspect, namely, a psychic aspect. It is simply the world seen from within.”

Instead of some kind of mystical pleroma, the so-called “collective unconscious” becomes in this perspective all of those powers which determine our fate which are beyond our conscious self. This includes our natural environment and our inherited culture. Jung wrote that

“the collective unconscious is simply Nature — and since Nature contains everything it also contains the unknown. … Everything that is stated or manifested by the psyche is an expression of the nature of things, whereof man is a part.”

This understanding of psyche is, I think, consistent with a naturalistic perspective in so far as it avoids the dualism of a lot of talk about “soul”. Also, it gives the subjective experience its due, something which the naturalistic perspective often fails to do.

Bill Plotkin calls this ecopsychological perspective a “soul-centered” approach. A “soul-centered” Paganism can potentially combine the earth-centric drive to connect to the more-than-human world with the Self-centric search for greater wholeness, the two being facets of the same drive. From the “soul-centered” perspective, both earth-centered and Self-centered Paganism seek a transcendence of the ego and a transpersonal wholeness. Adrian Harris calls this “Self-realization”, a term he borrows from Arne Naess, the father of deep ecology. It is no coincidence that the term is also used in depth psychology. (Naess borrows the term from Gandhi’s interpretation of the Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita. And many have recognized a connection between Jungian depth psychology and the Hindu philosophy of Advaita Vedanta for which the Gita is a source.)

Both earth-centered and Self-centered Paganism seek connection with the “other” — not Rudolf Otto’s “Wholly Other”, but Martin Buber’s and Emmanuel Levinas’ relational other. Earth-centered practice seeks this otherness or alterity in the psyche of the world (psyche tou kosmou or anima mundi), while Self-centered practice seeks it in the personal psyche. Ecopsychologists like James Hillman, Theodore Roszak, and Bill Plotkin see these two processes as connected. Hillman writes:

“an individual’s harmony with his or her ‘own deep self’ requires not merely a journey to the interior but a harmonizing with the environmental world. The deepest self cannot be confined to ‘in here’ because we can’t be sure it is not also or even entirely ‘out there’!”

Jung himself experienced something like this. The last words he wrote in his autobiography describe how increasing identification with the natural world led him to a decreasing identification with the ego:

“Yet there is so much that fills me: plants, animals, clouds, day and night, and the eternal in man. The more uncertain I have felt about myself, the more there has grown up in me a feeling of kinship with all things. In fact it seems to me as if that alienation which so long separated me from the world has become transferred into my own inner world, and has revealed to me an unexpected unfamiliarity with myself.”

Somatic Paganism

But how does this play out in practice? It is not enough to just go on practicing Self-centered Paganism and claim that it’s the same thing as earth-centered practice — which seems to be what a lot of Neo paganismdoes. An example of this is when Neopagans (mis)use Jung’s theory to facilely identify “inner” archetypes (like the “Great Mother”) with “outer” physical phenomena (like the Earth). This kind of projection is ego-centric and is precisely the opposite of what a truly Self-centered and earth-centered Paganism seeks. Nor do I think it is safe to assume that by trying to heal the earth (through direct environmental action for example) we can heal ourselves.

I confess that I do not have the answer to this problem. The two practices still feel different to me, in spite of all my theorizing that they are the same. Take my morning ritual which is more earth-centered and feels extroverted (outward-turned), whereas my evening devotional is more Self-centered and feels more introverted (inward-turned). While I can theorize that the inward is outward and vice versa, I still experience them differently.

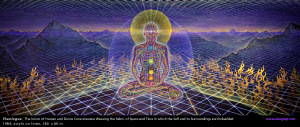

It seems to me that, if I am to discover how to meld these two practices, there is one place where I may find the answer: my body. The body is the place where our subjective experience and objective reality meet. It is the place where psyche meets nature, where inner and outer meet and mingle, where “me” blends imperceptibly into the “other”. I believe it is through my “body-self” that I may discover and connect the “gods within” (the archetypes of the unconscious) and the “gods without” (the immensities of nature).

I was first introduced to somatic practice in the context of my early Self-centered Pagan practice, through the writings of New Age author and former president of the Church of All Worlds, Anodea Judith, on chakras. Now, I know just the mention of the word “chakra” is likely to send many naturalists into a tailspin, but if you take away all the talk about “energy”, the premise that different parts of our body can “speak” to us is consistent with a naturalistic philosophy. Unfortunately, like many New Age authors, though, Judith tries to make a science of what is an art.

In addition to helping us connect with the “inner” psyche, somatic practice can be a vehicle for connecting with the “outer” psyche of nature. Adrian Harris has studied what might be the theoretical foundations of such a Somatic Paganism in his Ph.D. work: “The Wisdom of the Body: Embodied Knowing in Eco-Paganism” [abstract] [full thesis] and on his websites: embodiment.org.uk, thegreenfuse.org, and adrianharris.org. Harris draws on the work of Morris Berman, Gregory Bateson, Merleau-Ponty, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Wilhelm Reich, and others. Harris writes in his essay, “Sacred Ecology” that deep ecology, while valuable, is still fixed in the cerebral mode of the Western philosophical tradition. He proposes an even deeper deep ecology, one which moves beyond ratio-linguistic ways of knowing to “direct experience of a wholeness rooted in the body.” “Sacred ecology” is not an idea so much as an experience, what Harris calls “embodied knowing”, a practical and pre-reflexive way of knowing, which leads to a blurring of the boundary between self and other. This blurring is expressed well in the writings of David Abram, in which he describes how we are immersed in our landscape.

Harris believes that ritual in particular has the power to move us outside of the little box that is our head (what MacIver calls “craniocentrism”). Harris cites ritual theorist, Catherine Bell, Ronald Grimes, and Nick Crossley, as well as Wiccan and Religious Studies professor Nikki Bado-Fralick, for the proposition that ritual is a somatic strategy for producing an embodied form of knowing. Not all ritual will achieve this result though. Harris is critical of the highly structured ritual of esoteric and Wiccan Pagans, the goal of which is control and manipulation. He contrasts this with the more ecstatic and organic rituals of Eco-Pagan, the goal of which is connection. In addition to his thesis, on this point, see Harris’ essays, “A personal perspective on eco-magic” and “Eco-Paganism 101”.

In his thesis, Harris identifies several practices of Eco-Pagans which help create this felt sense of connection, including:

1) meditation (like Vipassana),

2) trance — not a out-of-body experience, but an experience of what Harris calls the “deep body”, “a deep embodied self that melts the boundaries between subject and object”,

3) ritual (especially ritual involving dance),

4) the “wilderness effect”, which Robert Greenway describes as psychological effects of being in wilderness for a period of a week or more, associated with extended trips in the U.S. wilderness as well as on some U.K. protest sites,

5) listening to the “threshold brook” (the term comes from Keats’ poem “The Human Seasons”), which Harris describes as fine-tuning our sensory awareness of the organic environment which results in a “deepening sense of place”,

6) the Focusing technique of Eugene Gendlin, which is used to draw attention to the “felt sense”, a tacit internal bodily awareness (expressed in the phrase “your body knows much that you don’t know”), and

7) the Heathen practice of “sitting out” (which resembles Setton sitting).

I myself have a practice which combines some elements of Harris’ “threshold brook” and Gendlin’s Focusing, with my version of the Quaker practice of silence. I previously posted about this practice that I call Listening to the Three Kindreds. This practice combines nature, psyche, and the body, though it still treats them as distinct. If Harris is correct though, these practices can result in an experience which blurs this distinction. This is something I hope to explore more in future posts.