Do we worship the same gods?

Over at Patheos, Star Foster recently published an interesting post on the “Problem of the Personal Experience”. In it she explains that she recently turned down the opportunity to edit a devotional anthology to the god Hephaistos, who she worships. She writes: “The reason I couldn’t do it is because I have very strong personal relationship with Hephaistos. And all of those submissions bore little relevance to my personal relationship to him.” She goes on to explain that many of the submissions were beautiful, but she could not relate to them. To give some context, Star is a hard polytheist or deity-centered Pagan who believes that Hephaistos “truly exists” in the same way that evangelical Christians, for example, believe in their God, and she has developed a personal relationship with Hephaistos.

Although Star didn’t take her essay in this direction, I think her experience raises interesting questions about the objectiveness of polytheistic deities. Now, mind you, I know many polytheistic Pagans have had the opposite experience. In fact, one person, Anthony Hart-Jones, said so in the comments. Anthony writes that he developed a personal relationship with the Morrigan. When Anthony met another person who followed the Morrigan, he says their “mental images” bore only a passing resemblance, but the “personality” was the same.

But what happens when two people who worship the same god or goddess meet up and realize that they have very different conceptions of the deity? Are they worshiping the same god? Or two gods with the same name?

“On the one hand, I believe, with every fiber of my being, in the knowledge I have been made privy of by the Gods. I believe in my experiences and they are sacred to me. They run anywhere from synchronicious events to detailed biographies and some of them I will never share with anyone, they were that special. Throughout my practice, I have allowed UGP to push me forward in my path. […]

“On the other hand, there is UPG out there that contradicts mine, that I personally think is completely incorrect or that questions everything I believe in. Needless to say, this is UPG I struggle with. I can’t view it as invalid; I respect everyone’s path too much for that, but where does it fit in with my believes? We are talking about the same Gods, right?”

(emphasis added).

From a polytheistic perspective, there are ways to explain this. If the gods are persons, then it is possible for the gods to interact with different people in different way, to present different “faces”, as it were — just as we ourselves present different “faces” to different people. In fact, we sometimes speak as if we are different people in different situations or with different company. Perhaps this is true of the gods as well.

But is there another explanation? Is it possible to provide an account for polytheistic experience that is consistent with a naturalistic premise? Is there a naturalistic explanation for polytheistic experience that does not pathologize the experience and is consistent with polytheists’ own descriptions of their experiences?

Gods as Archetypes

Both Jung and “archetypes” have fallen out of favor in contemporary Pagan discourse, but I believe that is because Jung’s ideas have been watered down so that the term “archetype” has (incorrectly) become synonymous with “metaphor”. In this Jung-lite approach, the archetypal gods understood as mere metaphors for nature. But this is not what Jung had in mind when he spoke of archetypes.

The archetypes, according to Jung (in his mature thought), are “dynamic, instinctual complexes which determine psychic life.” (“Psychological Commentary on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, Collected Works, vol. 11). Jung saw the “gods” as anthropomorphic projections of the archetypes. The archetypes for Jung are ineffable and practically inexhaustible, characteristics that correlate with divine categories. Jung writes, “Psychologically speaking, the domain of ‘gods’ begins where consciousness leaves off […]” (“A Psychological Approach to the Dogma of the Trinity”, Collected Works, vol. 11). He explains that the ruling powers of the psyche compels “the same belief or fear, submission or devotion which a God would demand from [humankind].”

“[…] we seldom find anybody who is not influenced and indeed dominated by desires, habits, impulses, prejudices, resentments, and by every conceivable kind of complex. All these natural facts function exactly like an Olympus full of deities who want to be propitiated, served, feared and worshipped, not only by the individual owner of this assorted pantheon, but by everybody in his vicinity.” (“The History and Psychology of a Natural Symbol”, Collected Works, vol. 11).

The archetypes are not metaphors. They are form without content, potentialities rather than actualities. Their existence can only be inferred from our experience of archetypal images, which are necessarily only partial expressions of the archetype.

Archetypes as “Other”

For Jung, the most powerful religious experiences are archetypal experiences. This was not a reductive claim, as Jung believed that the religious quest was the most meaningful aspect of human experience. Archetypal experience is “numinous”, a term Jung borrowed from Rudolf Otto. According to Otto, the essential characteristic of the “numinous” is that it is mysterious or “wholly other”. The archetypal experience, then, is an experience, to one degree or another, of “otherness” within our own subjectivity. Jung described the power of the archetypes to fascinate, possess, and overcome us.

In the New Testament, for example, Paul spoke of “another law” at work within him. (Romans 7:15-23). Jung himself spoke of another “will” operating within him. He speaks of the experience of “spontaneous agencies”, and of “elements in ourselves which are strange to us”. And he describes the consciousness as being surrounded by “a multitude of little luminosities” or quasi-consciousnesses. (“On the Nature of the Psyche”, Collected Works, volume 8).

While the empiricist in him preferred the terms “unconscious” and “archetypes”, Jung explains that “God” and “daimon” are synonyms for the unconscious which convey the numinosity, the “otherness”, of the experience better:

“[Humankind] cannot grasp, comprehend, dominate them [numinous experiences]; nor can he free himself or escape from them, and therefore feels them as overpowering. Recognizing that they do not spring from his conscious personality, he calls them mana, daimon, or God. […] Therefore the validity of such terms as mana, daimon, or God can be neither disproved nor affirmed. We can, however, establish that the sense of strangeness connected with the experience of something objective, apparently outside the psyche, is indeed authentic.

“We know that something unknown, alien, does come our way, just as we know that we do not ourselves make a dream or an inspiration, but that it somehow arises of its own accord. What does happen to us in this manner can be said to emanate from mana, from a daimon, a god, or the unconscious. The first three terms have the great merit of including and evoking the emotional quality of numinosity, whereas the latter the unconscious is banal and therefore closer to reality. […] The unconscious is too neutral and rational a term to give much impetus to the imagination. […]

“The great advantage of the concepts ‘daimon’ and ‘God lies in making possible a much better objectification of the vis-a-vis, namely, a personification of it. Their emotional quality confers life and effectuality upon them.”

(italics added).

The Experience of the Archetypes

Sometimes archetypal experiences arise out of contact with wild nature, in which case they may be identified with objects in nature, as when we name a place with the name of deity. (Perhaps this is how animism first arose.) Other times, archetypal experiences occur in the context of religious ritual, in which case they may be identified with the paraphernalia of the ritual. (This may be how totemism first arose.) In both these cases, the archetypal image may be equated with some object separate from us. But archetypal experiences do not always occur through interaction with an object. Sometimes, as in the case of dreams or active imagination, there is no external referent. (This may explain how spiritualism first arose.)

Regarding his own experimentation with active imagination (the subject of a future post), Jung wrote:

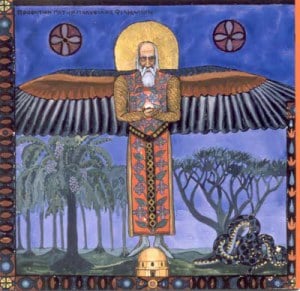

“Philemon [Jung’s personal image of the “Wise Old Man” archetype] and other figures of my fantasies brought home to me the crucial insight that there are things in the psyche which I do not produce, but which produce themselves and have their own life. Philemon represented a force that was not myself. In my fantasies I held conversations with him, and he said things which I had not consciously thought. […] I understood that there is something in me which can say things that I do not know and do not intend, things which may even be directed against me. […] Psychologically, Philemon represented superior insight. He was a mysterious figure to me. At times he seemed to me quite real, as if he were a living personality.” (Memories, Dreams, Reflections).

Jung’s description of his own encounter with the archetypes here is fascinating from a polytheistic perspective. Jung acknowledges that his experience of an archetype was of a personality, something separate from what he identified as “I”. This experience of otherness within one’s own subjectivity can manifest in subtle ways such as inspiration, and in less subtle ways such as divine revelation, schizophrenia, or even so-called “spirit possession”. It should be evident that we are not speaking of mere metaphors here.

“Although everything is experienced in image form, i.e., symbolically, it is by no means a question of fictitious dangers but of very real risks upon which the fate of a whole life may depend. The chief danger is that of succumbing to the fascinating influence of the archetypes, and this is most likely to happen when the archetypal images are not made conscious. If there is already a predisposition to psychosis, it may even happen that the archetypal figures, which are endowed with a certain autonomy anyway on account of their natural numinosity, will escape from conscious control altogether and become completely independent, thus producing the phenomena of possession.” (“Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious”, Collected Works, vol. 9).

Jung could describe divine visitation and spirit possession as psychological, because for him the psyche was both more capacious and less unitary than what we ordinarily think of as the mind. It is indeed a “cosmos”. So is Jung saying it’s “all in our heads”? Yes. But, as Lon Milo Duquette writes, “you just have no idea how big your head is.” Jung explains:

“… the individual imagines that he has caught the [unconscious] psyche and holds her in the hollow of his hand. He is even making a science of her in the absurd supposition that the intellect, which is but a part and a function of the psyche, is sufficient to comprehend the much greater whole. In reality the psyche is the mother and the maker, the subject and even the possibility of consciousness itself. It reaches so far beyond the boundaries of consciousness that the latter could easily be compared to an island in the ocean. Whereas the island is small and narrow, the ocean is immensely wide and deep and contains a life infinitely surpassing, in kind and degree, anything known on the island so that if it is a question of space, it does not matter whether the gods are ‘inside’ or ‘outside.'”

The Nature of the Archetypes

Jung’s view on the ontological nature of the archetypes is notoriously difficult to nail down. For one thing, his views evolved over his career, so it is possible to pull contradictory statements out of different works. For another, Jung’s writing is rarely a model of scientific clarity. But perhaps the most important reason is because he intentionally maintained a certain ambiguity on this issue. Charles D. Laughlin writes:

“I believe that the ambiguity was necessitated by Jung’s inability to scientifically reconcile his conviction that the archetypes are at once embodied structures and bear the imprint of the divine; that is, the archetypes are both structures within the human body, and represent the domain of spirit. Jung’s intention was clearly a unitary one, and yet his ontology seemed often to be dualistic, as well as persistently ambiguous, and was necessarily so because the science of his day could not envision a non-dualistic conception of spirit and matter.” (“Archetypes, Neurognosis, and the Quantum Sea”, Journal of Scientific Exploration, vol. 10, no. 3 (1996)).

For Jung, the archetypes have both a material aspect (brain) and a non-material aspect (experience). New Age writers have a tendency to describe the archetypes as if they are Platonic forms, but Jung considered himself an empiricist and insisted on the biological nature of the archetypes:

“They [the archetypes] are inherited with the brain structure – indeed they are its psychic aspect. […] They are thus […] that portion through which the psyche is attached to nature, or in which its link with the earth and the world appears at its most tangible.” (“Mind and Earth”, Collected Works, vol. 10).

In spite of his commitment to empiricism, Jung rejected reductive forms of materialism. On the other hand, Jung also sought to avoid the opposite problem of psychologism, which reduced the gods to illusions. For Jung, the material and non-material aspects of the archetypes are two different aspects of the same thing, seen from two perspectives, one objective and one subjective. In philosophical terms, Jung was a “neutral monist” and adopted a “double aspect theory” to explain the relationship between the physical and the psychic.

In Jung’s view, the “gods” are term for the subjective experience of the archetypes. And Jung believed this was the only meaningful way to speak about gods. So, if I were to ask if the gods are “objectively real”, I would have to say “no” — at least not in the sense in which rocks, and dirt, and the sun are real. In Jung’s view, it makes no sense to speak of the gods apart from our own experience of them.

“… it is not possible to maintain any non-psychological doctrine about the gods. If the historical process of world despiritualization continues as hitherto, then everything of a divine or daemonic character out side us must return to the psyche, to the inside of the unknown man, whence it apparently originated.” (“The History and Psychology of a Natural Symbol”, Collected Works, vol. 11).

If human beings ceased to exist, then so would the gods. The gods have no ontological status apart from us. They have no transcendental referent. While they sometimes arise through our interaction with the world, this is not necessary. They may be a purely internal experience.

Polytheism and the Archetypes

Jungian theory explains why the experience one polytheist of a certain deity devotee could diverge from another’s. But it also explains why they are the sometimes the same, why Anthony’s experience (above) resembled that of another worshiper of the Morrigan. The answer is what Jung called the “collective unconscious”. The “collective unconscious” is a term which has been much abused and misunderstood, but I believe it can be explained from a naturalistic perspective.

In Affective Neuroscience (1998), neuroscientist and psychobiologist Jaak Panksepp writes:

“… our brains resemble old museums that contain many of the archetypal markings of our evolutionary past. … Our brains are full of ancestral memories and processes that guide our actions and dreams but rarely emerge unadulterated by cortico-cultural influences during our everyday activities.”

This statement could easily have been written by Jung, instead of a neuroscientist. Because we share a biology and because groups of us share certain cultural conditioning, we can expect that certain of archetypal experiences will be similar in two people who have not interacted before. This is why we find similar motifs in the mythology of cultures separated by time and space, and this is why Anthony’s experience (above) resembles that of other devotees of the Morrigan.

Jung’s theory of the gods is, I believe, consistent with polytheist’s own descriptions of their experiences. Polytheists often describe the gods as needing human worship to give them existence, something like an egregore. I first encountered this idea expressed in the a 1967 episode of Star Trek titled “Who Mourns for Adonis?”, and later in Neil Gaiman’s 2001 book American Gods. (I have a theory that Gaiman’s book may have had a direct influence on the growth of hard polytheism in the Pagan community.) Perhaps the idea of egregores can be seen as polytheists’ way of acknowledging the subjectivity of gods. While some polytheists insist on the objectivity of their deities, I have seen more say that the question is irrelevant to them.

Still, to speak about the gods as subjective may seem reductive to some polytheists. When the world is examined through the objective lens of science, I maintain that the gods are absent. But, of course, this is also true of many other human experiences, like love, awe, and self-transcendence — experiences which many people describe as the most “real” experiences of their lives. A neuroscientist may reduce any of these experiences to biochemical reactions or light spots on an MRI, but such an explanation does not fully account for the experience. Something is missing from the purely objective description which the poet tries to express through words, an artist through paint or other media, the musician through an instrument, the dancer through movement, and the contemporary Pagan through ritual and myth.

I have written elsewhere about the need to emphasize the “otherness” of the archetypes. Jung warned against identification with the archetypes, which he called “inflation”. By emphasizing the otherness of the gods, we avoid reducing them to mere metaphors and we preserve the sense of danger that arises from interacting with the gods. On the other hand, it is possible to overemphasize the otherness of the gods, and this is what I believe polytheists do when they insist that their gods exist as distinct beings. What Christian theologian R. H. J. Steuart wrote about the Christian God could just as well have been written about polytheistic deities:

“We are obliged to preserve the concept of the ‘otherness’ of God [or the gods] from ourselves even though we cannot use it without distorting or at least wrongly stressing it. […] It is an otherness which not only does not exclude but positively (just because it is what it is) includes and demands oneness — a oneness, indeed, which is actually more real and intimate than what we would normally describe as identification.”