This is a difficult post to write. For one thing, I have the feeling like I’m about to stick my foot in my mouth. It comes with the territory … because I’m privileged. And privileged people are always sticking our feet in our mouths. That’s because we are generally unconscious of the ways we are privileged, and so we take a lot for granted. As a result we end up excluding others, mostly (I hope) unintentionally. But I’m going to plow ahead anyway (in characteristically privileged fashion).

Privilege has been a hot topic in the Pagan community the last few years. There’s been talk about heterosexual and cisgender privilege, white privilege, able-bodied privilege, thin privilege, Christian privilege. The highlight was probably the “Pagans and Privilege” panel at Pantheacon this past February, which T. Thorn Coyle hosted, and which had everyone buzzing. I always feel awkward in these discussions because I am privileged in just about every way one can identify. One blogger recently wrote:

Privilege has been a hot topic in the Pagan community the last few years. There’s been talk about heterosexual and cisgender privilege, white privilege, able-bodied privilege, thin privilege, Christian privilege. The highlight was probably the “Pagans and Privilege” panel at Pantheacon this past February, which T. Thorn Coyle hosted, and which had everyone buzzing. I always feel awkward in these discussions because I am privileged in just about every way one can identify. One blogger recently wrote:

“It’s easily argued that, in Anglophonic society, those who are ‘most privileged’ tend to have the following traits in common: white / Caucasian in skin colour, male, heterosexual, cisgender, masculine-presenting, able-bodied, about 20-35 years old, middle-income and bourgeois-aspiring, Christian, taller than “average” in height (US-born men average about 5’8″, UK-born men tend to average about 5’9″ –sorry Jon Stewart, you ARE NOT “short”), speaks English as a first language, is fairly attractive, and is in physical condition comparable to that of a minor league baseball player.”

I felt like this blogger was describing me. With the exception of “Christian”, the description above fits me pretty well. I’m male, white, heterosexual, masculine-presenting, able-bodied, 38, above-median household income, sometimes-bourgeois-aspiring, 5′ 9″, fair-skinned and blond, speak English as a first language, thin, and healthy. In any other context, this would sound like an application for a dating service. Here, it sounds like a confession. Why is that?

The only category which clearly does not apply to me is “Christian”, and that’s by choice. (Although I do have some Christo-Pagan tendencies.) And the one insular minority status I used to be able to claim — Mormon — I voluntarily surrendered. And that’s not to mention all the privileges which just come along with living in a first world country: clean drinking water, having enough to eat, sanitation, respect for rule of law, and being largely insulated from the devastating human impact on the environment. (Of course, all of these are a matter of degree.)

And then recently I came across a new “privilege”: “Wiccanate privilege”. This privilege manifests itself as the assumption that Neo-Wiccan ritual forms and theology are representative of all of Paganism. Though I don’t identify as Wiccan, my Neo-Paganism definitely has its roots in Wicca. So even within Paganism, I am among the privileged.

I’ve written before about being embarrassed of other people’s Paganism, a feeling that a surprising number of people admitted they sympathized with. Now, I’m feeling the flip side of this: other Pagans’ embarrassment of me. In various small ways, I have gotten the impression over the years at Pagan gatherings that I don’t really fit in with most other Pagans. In spite of celebrating the Wheel of the Year and being politically liberal (two of the most obvious indicia of being Neo-Pagan), I have often felt at Pagan gatherings that I am too square to be Pagan: too clean-cut, too middle-class, too conventional, too straight, too male. Kind of like Buzz Lightyear coming to the Island of Misfit Toys. On the internet, the feeling is less subtle, approaching real animosity. I feel it most acutely when I disclose to other Pagans that I am a lawyer. Something about my being a lawyer just sets some Pagans off. Maybe “lawyer” just screams “establishment”, or “sell out”, … or “privilege”. Honestly, I don’t know if I am imagining this. It could just be my own self-consciousness. But just it case it’s not …

I’ve written before about being embarrassed of other people’s Paganism, a feeling that a surprising number of people admitted they sympathized with. Now, I’m feeling the flip side of this: other Pagans’ embarrassment of me. In various small ways, I have gotten the impression over the years at Pagan gatherings that I don’t really fit in with most other Pagans. In spite of celebrating the Wheel of the Year and being politically liberal (two of the most obvious indicia of being Neo-Pagan), I have often felt at Pagan gatherings that I am too square to be Pagan: too clean-cut, too middle-class, too conventional, too straight, too male. Kind of like Buzz Lightyear coming to the Island of Misfit Toys. On the internet, the feeling is less subtle, approaching real animosity. I feel it most acutely when I disclose to other Pagans that I am a lawyer. Something about my being a lawyer just sets some Pagans off. Maybe “lawyer” just screams “establishment”, or “sell out”, … or “privilege”. Honestly, I don’t know if I am imagining this. It could just be my own self-consciousness. But just it case it’s not …

I’m not about to tell you that white males are the new “minority” or that this tiny amount of discomfort that I have felt is even in the same universe as what various minorities suffer on a daily basis. And I am not asking anyone to feel sorry for me because I’m privileged. And perhaps it is only right that I, multiply-privileged as I am, should feel just a little bit of what it’s like to be judged for who you are.

But it does sometime seem like some of the Pagan rhetoric about privilege is unnecessarily condemnatory of the privileged. It is one thing to condemn the ignorance and injustice that privilege breeds, and another to condemn the privileged themselves. Some privileges are the product of choice, and some of those choices are unethical. This is something that has been highlighted recently by the Occupy movement. But not all privilege is the product of unethical conduct. Most privilege — like being white, male, and heterosexual — is an accident of birth. As T. Thorn Coyle wrote after Pantheacon: “Having privilege doesn’t make us bad people, or bad Pagans. It just means we have access to things that others don’t.” What we choose to do with the privilege is what makes us ethical or not.

There is something ironic about some Pagans condemning someone for being white, male, straight, etc. This kind of othering is antithetical to the spirit of Paganism as I understand it. Alison Leigh Lilly (a not-infrequent critic of my own unconscious chauvinism) articulately this much more cogently that I could:

“I find myself disturbed by the frequency of arguments that declare: “We as Pagans should care about this cause because we, like the GLBT community [or other minority group], are also a minority and so what happens to them could happen to us.” Such an argument recognizes, sure enough, the themes of intolerance and hatred in the mainstream that unite us as a religious minority with other marginalized communities […] Yet such reasoning encourages us to continue to care for and sympathize only with others “like us” — even if they are like us primarily in their socially-defined otherness. It implies that our responsibility to concern ourselves with the problems of the marginalized lasts only as long as we ourselves feel the threat of that marginalization. The ethic of privilege remains unchallenged; we’ve merely succeeded in exchanging one privileged group (the mainstream or majority, conceived as the Western (Christian) white male) for another.

“The real challenge, I believe, is to continue to engage in social movements that reject and dismantle the hierarchical, patriarchal and hegemonic systems that give rise to intolerance and hatred towards “the Other,” while at the same time bringing this challenge home to ourselves in a very personal way. It is not enough to identify and care for those groups whom society has ignored, dismissed or overlooked. As individuals, we also have a responsibility to examine our own social and interpersonal relationships, in order to discover those communities and individuals that we ourselves are inclined to dismiss or marginalize.”

Some of us have sought out Paganism without having suffered so many of the “slings and arrows of outrageous Fortune” as our fellow Pagans. Should we be denied beloved community then? Does not the fact that we have come mean something? Is that not what binds us together as a community? Not that we have all suffered exclusion, but that we have all sought out this place, this place we call Paganism? And do we, the privileged, not have something to offer this community? Christine Hoff Kraemer recently asked this question in the comments to a post on another blog which was, in part, about the place of the “radical” in Paganism:

This is to say, perhaps, that we ought to value our (apparently) straight male white and other privileged-looking Pagans and do our best to communicate well with them, because they are a bridge between the most radical of us and a wider culture that is incapable of taking a perceived radical seriously.

Maybe you don’t want a bridge to the “wider culture”. Maybe it is refuge that you most need right now, shelter from all those slings and arrows. And perhaps my presence — white, male, heterosexual, middle class etc. — feels like an invasion of your sanctuary. After all, I can go anywhere. I can blend in. Why do I have to come here, to Paganism, and spoil its pristine nonconformity?

I don’t know that I have an answer, except to say that this feel like home to me. And part of what makes it feel like home is you being here.

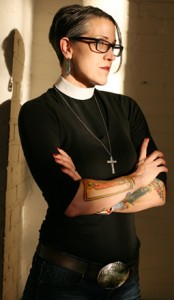

I’m reminded of a story that radical Christian pastor, Nadia Bolz-Weber, told on NPR about what happened when conventional types started coming to her church, the House for All Sinners and Saints:

[…] when my church was mostly young adults, and it was sort of, you know, hip, urban young adults. And then I preached at Red Rocks Easter Sunrise services — 10,000 people. And The Denver Post ran a front-page, full-page picture and story about me on preaching at Easter, and about my church and whatnot. And we only had about 40, 45 people every week at this point. And the next week, we doubled in size like overnight.

And we were excited because we were really struggling to grow, but what happened was it was like the wrong kind of people. I mean, it was the wrong kind of different for us, right? Like some churches might freak out if the drag queens show up, but these were like bankers wearing Dockers, right? And we were like …

(laughter)

[…] I freaked out. This actually isn’t a joke. I freaked out. And I kind of went on this little rampage about, like wait a minute. They could show up to any mainline Protestant church in the city and see a room full of people that looked just like them, right? And like, why are they coming — it was almost like, oh, well, this just so neat! Oh, this church is neat! They’re so creative! You know, and I just thought you’re ruining our thing, man; you are like messing it up.

[…] So we moved and then that was the first service with all the new people, right? And it was like this stately, historic neighborhood instead of the like grungy hipster neighborhood we came from. And I turned to this woman who’s like my deacon, and I was like, “We got to get the hell out of this neighborhood because it’s attracting the wrong element.”

(laughter)

[…] and I would call my friends and I’d rant about it and what am I going to do, and I called one of my friends who has a similar type of church in St. Paul, Minnesota, called House of Mercy. And I called up Russell, and I was like, “Dude, have you ever had normal people take over your church?”

And so I go on this — I tell him the whole story expecting him to be like, man, that sucks, and instead he goes, because our community holds this value of welcoming the stranger, and he goes, “Yeah, you guys are really good at welcoming the stranger when its a young transgender kid, but sometimes the stranger looks like your mom and dad.”

[…]

And we had the meeting and I told that story and the people who were new told us who they were and why they were there so that the people who’ve been there from the beginning could hear what the church is about. And then everyone went around in a circle and Asher said, “Look, as the young transgender kid who was welcomed into this community, I just want to go on the record as saying I’m glad there’s people who look like my mom and dad here, because they love me in a way my mom and dad can’t.”

I think perhaps we Pagans might take take a page from the Christians’ book in this instance:

“While the Goddess was having cakes and ale at Pagan Spirit Gathering, many lawyers and middle-class soccer dads were eating with her and her circle, for there were many who followed her. When the transexual devotional polytheist saw her eating with the lawyers and the soccer dads, they asked the Pagans: ‘Why does she eat with lawyers and soccer dads?’ On hearing this, the Goddess said to them, ‘It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.'” (my version of Mark 2:15-17).