And the Church must be forever building, and always decaying.

and always being restored.…

The Church must be forever building, for it is forever decaying

within and attacked from without;

For this is the law of life;

— T.S. Elliot

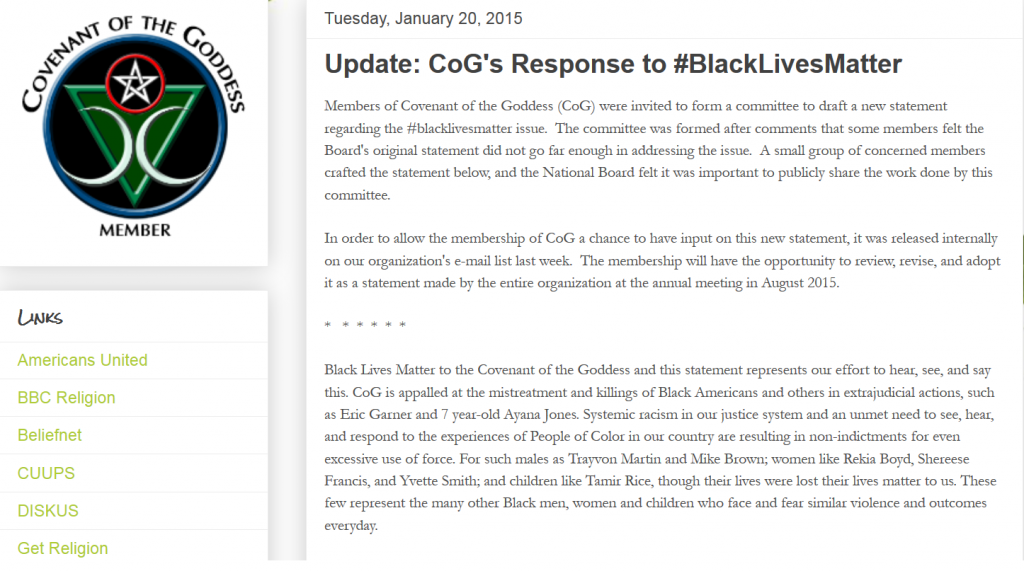

Two recent events have got me thinking about the lives of religious institutions. The first was the mess that the Pagan organization, Covenant of the Goddess (CoG), was recently embroiled in after releasing a highly problematic statement purportedly in support of #BlackLivesMatter. In response to public and internal criticism, a proposed revised statement was recently released by CoG. Rev. Kirk White, a former co-first officer of CoG observed that this latest controversy arises from a deeper problem: CoG has lost its sense of mission. “Part of the underlying problem is that CoG is adrift in its purpose and seeking to regain its relevance. … there is a struggle in CoG over how to restore relevance and attract younger members. The few younger members we do have and the more liberal members want CoG to be more activist to regain relevance.” If you want to know more about the whole thing, check out the article at The Wild Hunt about it.

This is a thread picked up by Kirk White, a former co-first officer who wonders about the covenant’s future. He said:

Part of the underlying problem is that CoG is adrift in its purpose and seeking to regain its relevance. Its foundational purpose was “to increase cooperation among Witches and to secure for Witches and covens the legal protection enjoyed by members of other religions.” Back in 1975 it was hard to connect with other Witches, get ordained, and we were still establishing our rights as a valid, legal religion. It was easy to rally the members around clearly Witch issues but now these battles are mostly won, ordination is laughably easy and we have the internet. So there is a struggle in CoG over how to restore relevance and attract younger members. The few younger members we do have and the more liberal members want CoG to be more activist to regain relevance.

But without clear Witch issues, the political polarization of our secular world is invading CoG’s inner processes over which causes to support. Environmental issues, women’s rights, gun rights, and racial inequality have all been split into “liberal” or “conservative” views by today’s media and CoG’s membership, being politically diverse finds itself unable to find consensus — which is how CoG operates — on just about anything. Thus, issues like #blacklivesmatter — originally seen as a “liberal” cause — are almost impossible to agree on quickly, if ever. This is frustrating to those more activist members, and combined with some bad blood left over from previous conflicts, has led to the recent resignations and bitter fighting within some of the more vocal parts of CoG.

– See more at: http://wildhunt.org/2015/01/cracks-in-the-cauldron-covenant-of-the-goddess-wrestles-with-its-role.html#sthash.U7ERuM5v.dpuf

The second event was the non-apology offered to LGBTs by Mormon leaders, following a press conference where they offered their non-support for LGBT rights. The press conference was ostensibly about the Mormon church’s support of some basic rights for LGBT people, but was, in fact, mostly about defending Mormons’ right to discriminate. Following the press conference, LDS apostle Dallin H. Oaks made a remarkable statement in response to calls for the church to apologize for its past rhetoric on homosexuality: “I know that the history of the church is not to seek apologies or to give them. We sometimes look back on issues and say, ‘Maybe that was counterproductive for what we wish to achieve,’ but we look forward and not backward.” The church doesn’t “seek apologies,” he said, “and we don’t give them.” He went on to make a similar point in a later video chat by insisting that the word “apology” doesn’t appear in LDS scriptures! The irony of this statement was noted by The Mormon Therapist (and fellow Patheos blogger), Natasha Helfer Parker, who observed that the LDS Church preaches repentance as one of their core doctrinal tenets: “How can we even make sense of the church and its leaders having some type of exemption card from a core commandment which, when followed, is supposed to lead to growth and eternal progression?” (Fortunately, some members of the LDS Church responded better than their church leaders.)

Both the Covenant of the Goddess and the LDS Church were guilty of a kind of privilege blindness (one of race and the other of sexual orientation). The difference between these two organizations was that CoG acted to remedy its error, whereas the Mormon church dug in its heels. While the Mormon church preaches repentance to its members, the idea that the church itself would ever repent probably seems strange to most Mormons. I was raised Mormon, which means that — like a lot of Catholics — I was raised to believe that my church was “the only true and living church upon the face of the whole earth” (Doctrine & Covenants 1:30). While many Mormons will will admit that their leaders are fallible, there is a widespread belief in the infallibility of the church itself, an idea which is built on Mormons’ understanding of the concepts of “apostasy” and “restoration”. Mormons believe that Jesus Christ established a church while he was alive and set his apostles up as its leaders. They believe that this church fell into “apostasy”, meaning basically that it lost the connection to God, which was only “restored” in the early 19th century by a farm boy in upstate New York named Joseph Smith. Mormons believe that the “true church” once “restored”, need never be restored again.

The idea of apostasy and restoration is a compelling one. It is easy to see signs of “apostasy” in any religious organization, where “apostasy” can be understood as meaning that the organization has lost its way in some sense. And it is natural to hope for “restoration” in these cases. In the Mormon case (like other fundamentalist religions), this “restoration” is envisioned as a return to an imagined ideal past which holds out the promise of certainty and intellectual repose. I have a quote by the Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., hanging on the wall of my law office, which reads: “Certainty is generally an illusion and repose is not the destiny of man[kind].” This quote reminds me that, while it is very human to long for certainty and intellectual repose, they are traps. They are traps for individuals, but also for organizations.

The T.S. Elliot quote which starts this essay suggests that religious organizations, like human beings, are organic things: they must evolve or they die. The problem with the Mormon conception of “restoration” is that it denies this reality, the reality of change. If restoration is understood something that only needed to happen to the church once, in the past, then the church becomes incapable of evolving further and it stagnates. There have, in fact, been numerous changes in the LDS Church, both large and small, since the days of Joseph Smith: changes to doctrine, changes to scripture, changes to ritual. But in spite of this, and in spite of a doctrine which claims that divine revelation is ongoing, the LDS church does whatever it can to resist change and to hide or downplay any evidence of change where it exists.

But this is not the only way to understand “restoration”. In contrast to the Utah-based Mormon church, another branch of the Latter-Day Saint movement, based in Missouri, previously called the “Reorganized” LDS (or RLDS) church, has been less reticent about embracing change — from ordaining women in 1984 to recently moving toward LGBT equality to changing its name to the more ecumenical “Community of Christ”. Not coincidentally, as far back as 1967, some of the intellectual leaders of the RLDS church made the case for a different understanding of “restoration”. Rather than a one-time event which restored the church to its pristine truth-fullness in the 19th century, they argued that restoration is an ongoing process: “… the idea of Restoration if it is to be used meaningfully, must refer to that process of response and renewal which every church or denomination needs be continually involved in.” In this sense, “apostasy” is not a deviation from the past, but a refusal to reconsider the present; and “restoration” is not a return to the past, but a renewal of the present.

I no longer belong to the Mormon church. And I’ve never belonged to the Covenant of the Goddess. As an outsider to both organizations, I see similar evidence in both of what might be called “apostasy”, in the form of institutional blindness to privilege (whether it be white privilege or hetero privilege) — but there is a critical difference in the respective responses of these two organizations. It is hard enough for individuals to admit they were wrong; it seems even harder for organizations to do so. Ironically, in this case, it was the Pagan organization that was more willing to “repent” and move toward real “restoration”. I am aware that many in the Pagan community are still outraged by CoG first statement, and I am not commenting here on the adequacy of CoG’s revised statement, nor am I seeking to excuse or diminish the significance of its original statement. But as a Pagan, I appreciate that it was the Pagan organization that at least tried to embody the nominally “Christian” principles which the Mormon organization I left behind has hypocritically eschewed.

The response of the Covenant of the Goddess to criticism is example of openness to (if not yet actualization of) renewal. And it is renewal that this season of Imbolc represents for many Pagans. As Erick Dupree writes:

“Imbolc … is a reminder of the promises I made to myself to regenerate, renew and restore the balance that comes from the fires of commitment needed to foster love, service, justice and peace. Imbolc is for me about the righteousness of possibility that is as fertile as the Earth herself. Here is this great promise, this invitation to transform our hearts and mind into the someone and something that is more than we were the previous season.”

May we all accept the invitation this season offers us to renew ourselves and our relations with the world.