3. Paganism and Christianity

In my previous post, I proposed that the reason why there are so few original winter solstice songs for Neopagans and the reason why the winter solstice is treated as a minor holiday by Neopagans is one and the same: Neopagans have an aversion to all things Christian. A good example of this, I think, is Star Foster’s resolution to boycott Christmas this last December.

As a former Christian myself, I understand this aversion. I tend to relate all Christianity (some of which is really quite inoffensive) to the Christianity that I experienced and rejected. It took me years and real inner work to admit that the Mormonism that I rejected was just my own idiosyncratic version of it, which not all Mormons shared. Still, I tend to highlight in my mind the most obnoxious aspects of Christianity (probably as a self-justification). Of course, this is not difficult to do, since the most obnoxious people (of any faith) seem to also be the loudest ones.

Nevertheless, even as I left Christianity behind, I felt very much drawn to those aspects of Christianity which seemed to me to be pagan-ish. I developed a real fascination for the pagan Hebrew culture, which is only hinted at in the Old Testament, but probably represented the majority view. (Check out William Dever’s Did God Have A Wife, for an accessible introduction to just one aspect of this topic.) I still feel that there are some fundamental, paradigmatic differences between the two religions. Even so, the pagan elements of Christianity remain very attractive to me today.

To begin with, the line between what is Christian and what is pagan has been a vague one from the start. The Carpocratians were a sect of Gnostics founded by Carpocrates of Alexandria that claimed Christ derived the mysteries of his religion from the Temple of Isis in Egypt, where he was said to have studied for six years, and that he taught them to his apostles. The sect endured until the sixth century. (See The Arcane Schools by John Yarker.) Another group, the Collyridians, were a group of Christian heretics in pagan Arabia who worshiped Mary, the mother of Jesus, as a goddess. Epiphanius of Salamis wrote that Collyridian women offered cakes to Mary, from which they take their name. It is possible that this was a continuation of the practice of making cakes for the Queen of Heaven described in Jeremiah.

Skipping forward a few hundred years, the Christianizing of pagan cults in late Antiquity is well documented and has become an important (although probably overstated) part of the Neopagan narrative. In one conspicuous example, in 596 CE, Pope Gregory sent a mission to England and advised Augustine of Canterbury to respect the customs of the Anglo-Saxons, but to replace pagan festivals with feast days of saints and also to consecrate pagan sanctuaries to Christ.

Skipping ahead a millennium, the Protestant reformers were convinced that the Catholic cult of the saints and popular entertainments associated with holidays represented a detritus of ancient pagan religion. We can debate the specifics, but it is evident that their perception of some elements of Catholic Christianity as vestigal paganism was not completely unfounded. As Fra Colonna declared in Charles Rease’s 1861 The Cloister and the Hearth:

“Our numerous altars in one church are heathen; the Jews, who are monotheists, have but one altar in a church. But the pagans had many, being polytheists, Our altars and our hundred lights around St. Peter’s tomb are pagan. We invent nothing, not even numerically. Our very Devil is the god Pan, horns and hoofs and all, but blackened. For we cannot draw; we can but daub the figures of Antiquity with a little sorry paint or soot. Our Moses hath stolen the horns of Ammon, our Wolfgang the hook of Saturn, and Janus bore the keys of heaven before St. Peter. All our really old Italian bronzes of the Virgin and Child are Venuses and Cupids.”

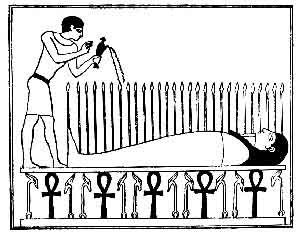

While Fra Colonna may have overstated the matter, we know that Easter combines various European and Middle Eastern traditions of spring fertility rites. Also, the cult of the Virgin Mary is a continuation of the ancient worship of the Anatolian Great Mother and the Egyptian goddess Isis. (Check out Stephen Benko’s The Virgin Goddess: Studies in the Christian and Pagan Roots of Mariology.) And perhaps most conspicuously, the modern Christian celebration of Christmas replaced the northern European pagan Yule holiday and the even older Roman solar worship. In fact, it was not until 273 CE that December 25 was adopted as the date of Christ’s nativity (in lieu of the spring equinox), previously, the Roman festival, Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (“birth of the unconquered Sun”).

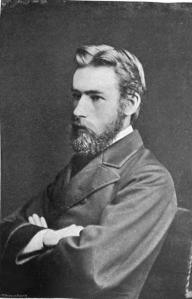

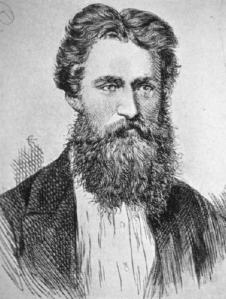

And this brings me to one of the ideas which actually drew me to Neopaganism: the myth of the dying and reviving god. The myth originates with James Frazer’s The Golden Bough. Frazer’s Bough influenced the Cambridge Ritualists, Samuel H. Hooke and Gilbert Murray, as well as Theodore Gaster, each of whom attempted to reconstruct a cycle of rites based on Frazer’s myth, synchronized to the seasonal cycle of planting and harvesting. The poet and novelist, Robert Graves, then took Frazer’s myth, gave new emphasis to the element of the goddess, and split the dying god into light and dark aspects. Finally, the Gravesian myth was gradually overlaid onto a calendar consisting of the Irish cross-quarter days and the Anglo-Saxon quarter days to constitute the Neopagan Wheel of the Year by Margaret Murray, Gerald Gardner, and those that followed them.

The interesting thing about the story of the origin of the Wheel of the Year is that it began with Jesus — specifically with Frazer’s intent to discredit Christianity by suggesting that the figure of Christ had been an outgrowth of the pagan belief in a dying and reviving vegetation spirit. In the second edition of the Bough, Frazer explicitly stated that the Christian story of the Crucifixion was derived from the sacrifice of god-kings, and that the Christ story belonged with “a multitude of other victims of a barbarous superstition.” Frazer’s purpose was not to legitimate ancient pagan practices, but to debunk all of religion, Christian and pagan, as superstition. The explicit condemnation of Christianity in The Golden Bough, however, was missing from the 1922 abridged version, which was the version most read by the public.

For Neopagans, Frazer’s modernist agenda is generally overlooked, and The Golden Bough is understood as reducing Christianity to just another form of the cult of the dying and reviving god. Ronald Hutton states that Frazer’s thesis “fostered not so much an enhanced respect for rationalism and progress as a delight in the primitive and the unreasonable.”

“[B]y placing Christ in a context of dying and resurrecting pagan deities, Frazer had hoped to discredit the whole package of religious ideas. Instead, as some of the literary use of the Bough indicates, he actually gave some solace to those disillusioned with traditional religion, by allowing them to conflate the figure of Jesus with the natural world.”

If there had not been a Jesus or a Christianity, there very likely would never have been a Golden Bough. Frazer would most likely never have written it, and even if he had, it definitely would not have become as influential as it has been (see John Vickery’s The Literary Impact of the Golden Bough).

Hutton’s book, The Triumph of the Moon, was the first book on Neopaganism that I read. So when I came to Neopaganism, I came looking for the religion of the dying pagan god and his goddess. Of course I found the goddess, but her dying and resurrecting consort was not as obvious. And I suspect that this is because of the Christo-phobia of many Neopagans.

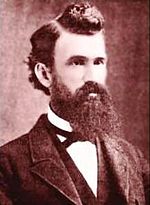

This aversion seems strange in light of the fact that the father of Neopagan witchcraft, Gerald Gardner, did not himself see any necessary contradiction between Christianity and witchcraft. Gardner wrote in The Meaning of Witchcraft:

“It is usually said that to be made a witch one must abjure Christianity; this is not true; but they naturally would not receive into their ranks anyone who was a very narrow Christian. They do not think that the real Jesus was literally the Son of God, but are quite prepared to accept that he was one of the Enlightened Ones, or Holy Men. That is the reason why witches do not think they were hypocrites ‘in times of persecution’ for going to church and honoring Christ, especially as so many of the old Sun-hero myths have been incorporated into Christianity; while others might bow to the Madonna, who is closely akin to their goddess of heaven.”

Gardner was not alone. This attitude toward Christianity was not unusual among proto-Neopagans: (1) Dion Fortune’s writings had a profound influence on Neopaganism, especially her fiction, while the Inner Light Society she founded remained Christian. In The Winged Bull, Fortune claimed that the Christian God was just one other equally valid aspect of the One God. (2) W. B. Yeats attempted to fuse Christian and pre-Christian traditions and resisted pressure to discard Christian elements from his mythology. The Golden Dawn Order itself, to which Yeats belonged, drew heavily on Christian and Hebrew symbolism. (3) Ernest Westlake, who founded the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry in 1916 as a Quaker-inspired alternative to the Boy Scouts, sought to revive the old gods of paganism, including Pan, Dionysus, Artemis, and Aphrodite. He did not view this practice as antithetical to Christianity, however. Hutton explains,

“To Ernest himself, the attraction of paganism was not that it would replace Christianity but that it would cope with precisely those areas in which the latter had become deficient, and so (at best) to help revivify it. He coined the aphorism ‘one must be a good pagan before one can be a good Christian.’”

One might claim that these proto-Pagans had just not developed a uniquely Pagan consciousness, which would only become fully formed in the 1960’s counterculture. But consider Aidan Kelly, one of the founders of NROOGD. One can hardly think of someone more immersed in the Neopagan milieu, and yet, when Kelly left Neopaganism to return to the Catholicism of this upbringing, he reported to Margot Adler that

“He now believes that all visions of a universal Goddess come from the influence of Christianity—not the reverse. The Goddess movement is not Pagan he says, but a radically dissenting type of Christian sect. It is not Mary who is a pale reflection of the Great Goddess, he argues, it is the idea of a Great Goddess that is dependent on ideas about the Virgin Mary. The Goddess, he says, is merely a ‘de-Christianized and backdated’ version of Mary. Even the vision of Isis in The Golden Ass by Apuleius is, he believes, a creation influenced by Christianity.”

Kelly’s suggestion that the Neopagan Goddess was derived from Mary is difficult to credit. In response to Kelly, Adler herself felt compelled, at least, to point out that many pagans worship not a “saccharine” figure resembling the Virgin Mary, but fierce goddesses who are warriors and destroyers, as well as creatrixes. I have to agree that it is the figure of Mary that seems to me to be derivative.

Nevertheless, there is perhaps a sense in which the Neopagan Goddess is a product of the Christian Mary. The origin of Neopagan Triple Goddess can be traced to Robert Graves, and from him to the Cambridge Ritualist, Jane Harrison. Harrison herself related the Mother and Virgin figures of Demeter and Kore to the Father and the Son in term of their relationship to each other, being two-in-one. She states in her Prologomena:

“It has been shown in detail that the Mother and the Maid are two persons, but one god, are but the young and old form of a divinity always waxing and waning. It is the same with the Father and the Son; his is one but he reflects two stages of the same human life.”

Harrison, in turn, was deeply influenced by Sir Arthur Evans and his discoveries from Crete as she described in her autobiography. Evan interpreted the Cretan deities as manifestations of a single Great Goddess and her subordinate son and consort. According to Hutton, Evans’ interpretation was based not only on the classical legend of Rhea and Zeus, “but his insistence that she had been viewed as both Virgin and Mother, with a divine child, owed an unmistakable debt to the Christian tradition of the Virgin Mary.” In short, there is a historical debt that the Neopagan Goddess owes to Mary. If there had not been a Virgin Mary, perhaps there would not have been a Neopagan Goddess — at least not as we now know her.

While Kelly’s claim that Neopaganism is a “radically dissenting Christian sect” seems exaggerated, it does raise a valid question of whether Neopaganism is truly “post-Christian”. Kelly is not the only one who has made this claim, though. In 1996, British religious studies scholar, Linda Woodhead, presented a paper at the Nature Religions Today conference in England, which was later reported on by Jone Salomonsen. According to the Salomonsen, Woodhead had suggested:

“that the ‘new spirituality’ that today flourishes in contemporary western societies represents a single form of religiosity, and that pagan Witchcraft is merely one of its expressions. This ‘new spirituality’ is deeply rooted in European Protestantism and has arisen as a response to an increasing dissatisfaction with Christianity (and Judaism) [emphasis original] […] Although the self-understanding of Witchcraft is to reject this whole tradition, not to revitalize it, nor purify it from within, Woodhead argues that the most important context in which to understand pagan Witchcraft is a Christian Context: Witchcraft is not a new religion, but a reformation.”

Salomonsen, for her part, appeared to agree that Witchcraft is not post-Christian, but only post-church or post-synagogue, a “subcultural branch of Jewish and Christian traditions.”

In 2007, Pearson took up this claim in her Wicca and the Christian Heritage: Ritual, Sex and Magic where she argued that Christianity is the “real invisible player” in the history of Wicca. Her book is a study of heterodox Christian movements of nineteenth century Britain and France. Although she stops short of Woodhead’s claim that Wicca is a “new reformation” or a “bastardized version of Christianity”, she nevertheless concludes that

“if heresy and witchcraft are constructs of the Christian imagination [as Wiccans claim], then a Christianity that has been constructed as ‘other’ by some Wiccans is also a product of imagination.”

A Jungian might suggest that the Neopagan animus toward Christianity is a function of our projection of our “shadow” onto the Christian “other”. Our “shadow” in this case is created by our repression of our consciousness of the Christian origins of contemporary Neopaganism. In projecting our shadow onto a Christian “other”, we create a caricature of Christianity which we can then demonize.

It is not just that Christianity was the historical precedent to Neopaganism. Michael York has suggested that Neopagan theology is essentially Christian. In “New Age and Paganism”, he observes that, Neopaganism’s polytheism, which is essentially monist, is distinct from that of ancient paganisms, which are essentially pluralist. According to York:

“Contemporary expressions of Neo-paganism are to me more of an updating and rectification perhaps of an essentially Christian attitude which is different from the free-ranging and loosely defined multiplicity of personalities and forces and deities which collectively constitute the [ancient] pagan [pantheon]”

While I cannot agree with the statement that Neopaganism is a Christian sect, I do agree that Neopaganism is an outgrowth of Christianity. This is not just to say that Neopaganism arose in the context of a Christian culture, but rather that Neopaganism as it exists today would not be but for Christianity, just as the Neopagan Goddess might not be, but for the Virgin Mary. This is true often on the personal level as well as on the corporate level. On the corporate level, Neopaganism as a movement grew out of and in reaction to Christianity. On a personal level, probably most Neopagan converts to Christianity came from a Christian background. And even those who did not came, for the most part, from a culture with is predominately Christian.

Coming to terms with our Christian origins is, I believe, necessary to the maturation of the Neopagan movement. I recently read a response to Teo’s by C. Aine Pearson which went as follows:

“In Paganism, I find fundamental acceptance of the me that was, the me that is and the me that will be. Acceptance as I /am/, with encouragement toward growth that does not hinge on attempting to achieve /perfection/; acceptance that the growth I experience does not imply that I was flawed before and am /better/ after.”

Acceptance of who we were must include an acceptance of our Christian origins. I have struggled a long time to make peace with my Christian past, and I still struggle. For many years, I looked at that time as lost time, and I resented it. I did not really understand that who I was then led to me being where I am now. A book by James W. Fowler, Stages of Faith, was instrumental in helping me come to terms with accepting who I has been. And I found that the more I accepted my past self, the less anger I had at the Christian faith that was a part of who I had been.

As I said above, I still feel that there are some fundamental, paradigmatic differences between the two religions. But I wonder what might happen in our movement if we began to understand Neopaganism, not as a rejection of our Christian past, but as building upon that Christian past. I wonder if it might not make us more whole, as individuals and as a movement. So when we celebrated the winter solstice this year, I encouraged my children’s conflation of the baby Jesus with the reborn Sun God. And I sang those paganized Christmas carols with gusto.