In the nearly twenty years since a U.S.-led coalition invaded Afghanistan, over two thousand American troops and over a hundred thousand Afghans have died. There’s little that doesn’t feel tragic about that war as it crashes to an end, but it was particularly sad to add dozens more to that death toll on Thursday, when ISIS suicide bombers attacked Kabul airport in the midst of American forces withdrawing and some Afghans fleeing the return of the Taliban.

So even as he accepted responsibility “for, fundamentally, all that’s happened of late” in the last, chaotic days of the American war in Afghanistan, Joe Biden also took on the presidential role of mourner-in-chief. Paying tribute to the thirteen American service members who died on Thursday, our second Catholic president quoted the Old Testament:

Those who have served through the ages have drawn inspiration from the Book of Isaiah, when the Lord says, “Whom shall I send…who shall go for us?” And the American military has been answering for a long time: “Here am I, Lord. Send me.” “Here I am. Send me.”

No one disagreed that “these women and men of our armed forces are the heirs of that tradition of sacrifice of volunteering to go into harm’s way,” but many criticized his use of Scripture in that way.

Fair is fair. If I saw this coming out of Trump's mouth I'd call it #ChristianNationalism. Connecting military service & sacrifice with serving God is pretty textbook. I'm grateful to those who serve, but these sorts of statements pridefully imply they're God's representatives. https://t.co/UPclSTZ2kL

— Samuel Perry (@profsamperry) August 26, 2021

But to conservative commentator Mark Tooley, Biden’s quotation of Isaiah 6:8 was just another example of an American president using biblical language in the practice of civil religion, which he distinguished from Christian nationalism.

For my part, I can’t hear that verse without thinking of my favorite reflection on Christian vocation. “To Isaiah, the voice said, ‘Go,’” preached Frederick Buechner in 1969,

and for each of us there are many voices that say it, but the question is which one will we obey with our lives, which of the voices that call is to be the one we answer. No one can say, of course, except each for himself, but I believe that it is possible to say at least this in general to all of us: we should go with our lives where we most need to go and where we are most needed.

If Buechner is right, then not just prophets, but singers and statisticians and surgeons can answer, “Here I am, send me.”

Soldiers and sailors, too. But it’s hard not to use that verse as a eulogy for that particular vocation’s ultimate sacrifice without making it sound like such work is specially ordained by God — or without echoing themes of American exceptionalism.

In any case, Joe Biden is hardly the first American leader to make that rhetorical move. Religion reporter Jack Jenkins pointed out two prior examples. In 1996, Bill Clinton’s secretary of defense, William Perry, quoted Isaiah 6:8 in closing his commencement address at West Point: “At this critical point in our history, your Nation has asked, ‘Whom shall I send? Who will go for us?’ And today you have answered, ‘Here am I. Send me.’” Seven years later, one of Perry’s successors, Donald Rumsfeld, reportedly added that verse and others to intelligence reports during the war in Iraq.

All of which got me wondering how old a tradition this is, to understand Isaiah’s description of divine calling in explicitly military terms. With classes starting Monday, I don’t have time for anything like comprehensive research, but I did do a little digging yesterday, using some simple digital tools.

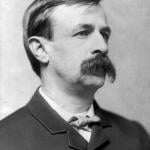

First, Lincoln Mullen’s wonderful resource, America’s Public Bible, which indexes quotations from the King James Version in the newspapers digitized in the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America project. Isaiah 6:8 shows up 183 times between 1840 and 1921 — not as often as a more famous 8th verse of a Hebrew prophet’s 6th chapter, but not rare either. For a long time, there seems to be no military implication at all. The first instance is fairly typical: a call to confession and revival from the Oberlin Evangelist (as reprinted in a Vermont paper). There are none from the period of the American Civil War, but then I found an October 1898 sermon in which Episcopal bishop Thomas F. Gailor preached on Isaiah 6:8 in the context of the Spanish-American War:

It was a vision of duty and responsibility, and [Isaiah] answered to his God, “Here am I, send me to bear the message that Thou desireth sent…” The revelation of God and the acceptance thereof, seem to me to be that sum and substance of all heroism.

But while Gailor saw that heroism “in the recognition of their duty of the heroes of our country in the charges at Santiago,” he also discerned it in the work of nurses in the Crimean War, in that “of the young man who accepts the call to a lonely parish,” and in the lives of earlier Christian leaders like Bernard of Clairvaux and William Wilberforce.

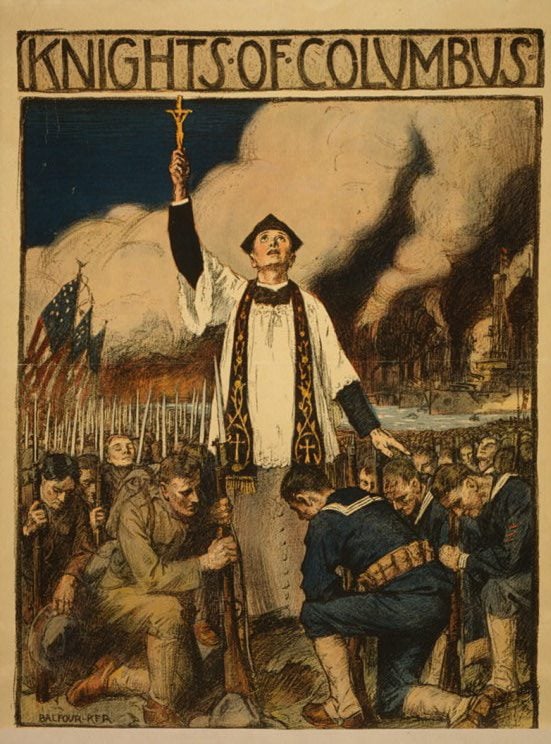

It took the First World War, I think, to suggest more distinctly militaristic readings of Isaiah 6:8. And not just among Christians. In May 1918, a Reformed Jewish magazine editorialized that “Judaism-in-action is expressed in sacrifice and service. Our young men are sacrificing and serving at the front… Will we answer, in the words of the Prophet Isaiah, ‘Here am I; send me’[?]”

Not long after the U.S. declared war on Germany, the International Sunday School Association asked its 18 million members to observe July 1, 1917 as “patriotic Sunday,” with each school directed to solicit offerings for the Army or war relief and “to encourage young men to enlist for active service in the war and young women for duty as Red Cross nurses….” The “golden text” for the day? “And I heard the voice of the Lord, saying, ‘Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?’ Then I said, ‘Here I am; send me.’”

One teaching plan for Patriotic Sunday instructed Sunday School teachers to liken the “real heroism” of Isaiah to the “true bravery” of a Revolutionary War soldier who volunteered to carry an important message through a Redcoat-infested forest. Comparing Kaiser Wilhelm to King Uzziah (who “had profaned the temple” at the time of Isaiah’s call), E. F. Daugherty turned Isaiah 6 into an anti-Prussian parable in the the Sunday School section of the June 21, 1917 issue of The Christian Century, “Isaiah was no slacker,” he warned any young Christian tempted to opt out of a civilizational struggle. “The puny reasons why he might have ‘claimed exemption’ were all but spider-web before the call of necessity. The slacker… is beneath contempt in a land of the free — and no more than a dry tare in the church of the living God.”

Still, other readings of the text persisted, even in the heat of wartime. In the Sunday School insert published in many American newspapers the last week of June 1917, E.O. Sellers concluded his overview of Isaiah 6 with a suggested application that was both less overtly militaristic and more explicitly (Christian) nationalistic in tone:

We are a Christian nation, but there are many degrees and kinds of Christians; those who sincerely try to follow Jesus; those who live under a Christian government, and are unaffected by Christian influences. There is only one way to save this nation from going the way of Nineveh and Tyre; that is, that justice and righteousness shall be the fruit of regenerated lives. The cry is for a better social environment and a more just social position.

Sellers worked for Moody Bible Institute. In another part of Chicago that first week of July 1917, Bishop H.B. Parks paid tribute to the pastor of St. Mary’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, recalling how Rev. Floyd Grant Snelson had also “said, ‘Here am I, send me’” — not to France or Belgium as a military chaplain, but to Africa, where a younger Snelson had served as a missionary and built two churches.

That sort of application of the passage also showed up near the end of the Second World War. In August 1945, as war raged in the Pacific, the Marion (NC) Progress placed Isaiah 6:8 on its front page. Next to the photos of three local brothers in uniform, an article reported on a Baptist pastor who had turned “Here Am I, Send Me” into a call for missionaries to Africa and China.

While Shia LaBeouf’s character in Fury invokes Isaiah 6:8 to explain his service, I’m not sure just how popular that verse was during WWII. I found it quoted just twenty times in Chronicling America for 1941-1945, and only one of those instances connected matters spiritual and military. Two weeks after Japan’s surrender, another North Carolina paper published a prayer asking that, “To every call of a national duty may our response be prompt: ‘Here am I, send me.’ So, as good soldiers of Jesus Christ, we would serve our day and generation.” But the service the writer emphasized was no longer combat, but the work of caring for those “who have offered their bodies in battle,” and for “all who suffer want and are lonely and discouraged.”

So much for my spotty, idiosyncratic research… I’d be interested to learn of other historical examples of this theme, or to hear from readers who served in the military: Was the message of “Here I am, send me” invoked during your service? Has it become more common recently, or was it part of military-religious culture in the Gulf War, Vietnam, or earlier?