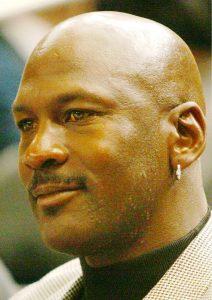

Who is the GOAT (greatest of all time) in basketball? Some believe this is not a valid question because it is unfair to compare players from different eras as how the game is played has changed quite dramatically over the years. I believe this is an irrelevant question to ask because the answer is too obvious, it is Michael Jordan. As a Muslim, one side of me is tempted to name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as the GOAT since he is NBA’s all time leading scorer and won one more “Most Valuable Player” award than Jordan did. Yet, anyone who witnessed Jordan’s prime years would appreciate that there are things that cannot be reduced to numbers. Latest Jordan documentary The Last Dance aims to explain what makes Jordan so special. The documentary also reveals a lot about how the line between sacred and profane gets blurred in the basketball court. As a sociologist, I will try to ponder upon this latter question.

Who is the GOAT (greatest of all time) in basketball? Some believe this is not a valid question because it is unfair to compare players from different eras as how the game is played has changed quite dramatically over the years. I believe this is an irrelevant question to ask because the answer is too obvious, it is Michael Jordan. As a Muslim, one side of me is tempted to name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as the GOAT since he is NBA’s all time leading scorer and won one more “Most Valuable Player” award than Jordan did. Yet, anyone who witnessed Jordan’s prime years would appreciate that there are things that cannot be reduced to numbers. Latest Jordan documentary The Last Dance aims to explain what makes Jordan so special. The documentary also reveals a lot about how the line between sacred and profane gets blurred in the basketball court. As a sociologist, I will try to ponder upon this latter question.

From GOATs to Gods.

One of the hardest tasks early sociologists had to engage in was to find a definition for the concept of “religion”. Some religions lack the concept of deity, while others place God at the center of the universe. Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), the father of sociology of religion, took on this task and argued that there was a common feature in all religions. All religions based their beliefs and practices on the concept of sacred. Of course, the French sociologist believed, society was the ultimate judge to decide what sacred was. The Last Dance provides examples of a social group creating its own “sacred”. Jordan is frequently depicted as a divine figure. He was compared to the Pope by the French Press during Chicago Bulls’ trip to Paris in 1997. People were mobbing him wherever he went and even Jordan himself seemed to be surprised by adoration Europeans felt for him. The host of the French talk show program went further and described Jordan as “the person who is the closest to a god on earth.” Similarly, for fans, reporters and professional players Jordan was not just a hooper. He was the supreme sports personality with superhuman powers. Even legendary Larry Bird, one of Jordan’s archenemies, did not hesitate to ascribe divinity to Jordan in the documentary. According to Bird, it was not Jordan who scored 63 points against mighty Celtics in the 1986 playoffs, “it was just God disguised as Michael Jordan.” NBA superstars Allen Iverson and LeBron James made similar statements about Jordan. Iverson called Jordan “the black Jesus” while James suggested meeting Jordan for the first time was like meeting God. Jordan’s charisma on and off the court was so great that even his refusal to endorse African American Harvey Gantt in his home state of North Carolina senate race against ultra-conservative Republican candidate Jesse Helms in 1990 did not damage his reputation much in the eyes of his fans.

My intention here is not to illustrate how people worship or attribute divine properties to a particular basketball player. Instead it is to show how a profane activity like basketball could be recreated by society as a divine, transcendental phenomenon. Jordan serves as a great example but he was not alone in this sense. Some young sports fans worship Magic Johnson while others pray to a Larry Bird poster for success. Some others draw parallels between the life of Jesus Christ and LeBron James. (James, who is believed to be “the chosen one” left Cleveland, spent four years in Miami -which symbolizes the Paradise- and then came back to Cleveland to successfully end his mission.)

Some functions of the religion of basketball.

The structural-functionalist school in sociology claims that religion persists as a social institution because it carries out important functions in society. One such function is creating an identity for its followers and establishing unity among like-minded believers. From this perspective, religions are quite crucial for social peace and solidarity since they function as social glue. Religious rituals, in that regard, play a key role in strengthening and recreating these social bonds. As sociologist Harry Edwards noted in his Sociology of Sport, in the religion of sports this could be achieved through worshiping professional athletes. The Last Dance is a great example in this sense. The half man, half God Jordan narrative -especially through the discussions that take place on social media- creates a sense of community among basketball fans who believe that 1990s basketball stars are underrated and deserve more respect than contemporary NBA stars.

Marx and his followers, on the other hand, focus on a different function of religion. They believe religion is the opium of the people in the sense that it eases the pain of the oppressed segments of the society and thus prevents them from asking for a substantial change. Although political developments that took place in the 20th century, like liberation theology and the Vietnam antiwar movement, cast doubt on Marx’s assumptions and showed how at times Abrahamic religions could challenge the status quo and act as a revolutionary tool, Marx’s theory could be useful to understand the role basketball plays in American society. Noam Chomsky, for instance, argued that sports have been used by the capitalist system to divert working classes’ attention away from social and political issues that really matter. Onaje Woodbine’s ethnographic study on streetball players seems to support the same point. The study shows how kids from lower class families forget the difficulties they are facing in real life and seek comfort in the basketball court. In this respect basketball is a transcendental, spiritual experience. Some basketball players hope to achieve the American Dream and climb up the ladder of success as Jordan’s former teammates Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman did. As a result, the game of basketball seems to have the potential to integrate these lower segments of society into the system “peacefully”. Yet, as NBA Hall of Famer Charles Barkley suggests this so-called peaceful solution is destined to be short-lived as it is based on the illusion that all kids with talent would pursue a professional career in sports.

Poetry in motion.

Michael Zogry of the University of Kansas notes that the relationship between religion and basketball dates back to the very invention of the game. Physical education instructor James Naismith (1861-1939) was a religious man who believed the game of basketball could contribute to the development of young Christians’ personality. Today as The Last Dance illustrates, basketball seems to have lost the function Naismith was dreaming of. Instead it creates its own sacred, its gods, shrines and rituals. Even the fans knowing that these are not real gods does not change the fact that the line between profane and sacred is blurred in today’s basketball. Sociology would have us consider that this tendency could be ascribed to human being’s search for deeper meanings even in the secular realm more than to Jordan’s personal achievements and charisma.