By Matthew Allen

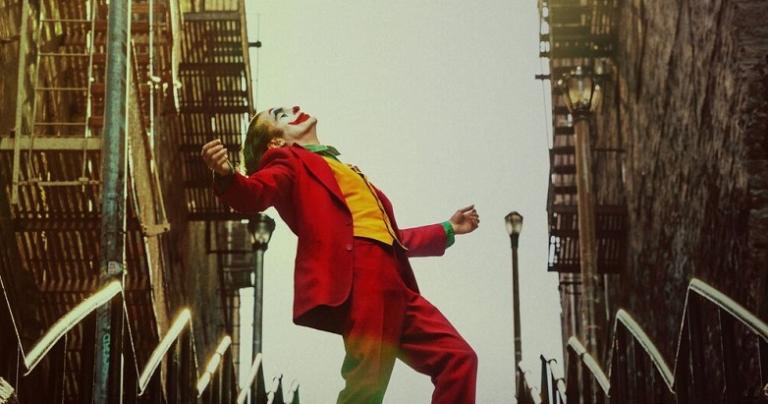

Summer is here. And, with uni done, I’ve had some time on my hands… a lot more time! No sooner had I hit “submit” on that last assignment — always a glorious feeling — than I decided that a good movie would really hit the spot. So, perusing a menu of cinematic delights, I settled on Todd Phillips’ 2019 production, “Joker.” Cue title. The following two hours plated up one evocative scene after another from the “cold, dark world” of Gotham City, as Phillips narrated the origins of Batman’s old archenemy.

But this was no superhero flick; it was, instead, a portrait of a deeply troubled — and all too familiar — postmodern society. Bringing an appetite for social commentary to the table, I found plenty to digest. As I drank the film to its haunting dregs, I called on scripture for help — and, oh, did I need it — in settling the questions Joker was asking of me.

One dilemma towered over the others: How can religious faith help to stem the crisis of meaning in our world, a theme so vividly rendered in Joker? To tackle this conundrum, I leaned on Hebrews 11: 1, ‘Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see.’

Defying Hopelessness

Arthur Fleck, who will become the Joker by the end of the film, is a man without any hope to stand on: the total antithesis of Hebrews 11. He pretty much fits the dictionary definition of a nihilist: ‘a person who believes that life is meaningless and rejects all religious and moral principles.’ This bleak worldview comes out strongly in a monologue Arthur delivers near the film’s cataclysmic ending. “My life is nothing but a comedy,” the Joker quips, “Everybody is awful these days. It’s enough to make anyone crazy.”

Phillips has been at pains to show that Arthur’s anger at society is not unjustified. A socially challenged recluse, the soon-to-be Joker lives in a dingy flat with his ailing mother. Urban life in a postmodern city has dealt Arthur a cruel hand. Suffering from involuntary fits of laughter, into the bargain, Arthur meets with nothing but ridicule as he struggles to get by.

To make matters yet worse, a round of budget cuts to social services in Gotham City has left Arthur without recourse to counselling or medication. He pleads with his therapist — even, perhaps, with God — “I just don’t want to feel so bad anymore.” It’s the cry for help of a man at rock bottom.

Now, there are some questions to which not even the Bible has an immediate reply; but what scripture does offer, as in Hebrews 11, is an overarching narrative of hope which transcends history. Some preachers and writers will try to market scripture as a catalog of easy solutions for all of life’s ills; whereas it’s really a promise of hope, implanted now in believers as a seedling faith, which comes to fruition only on the final day.

Yes, “the whole creation groans” (Romans 8: 22), but the promise of Hebrews 11 is no less credible. There is, as Marilynne Robinson described it, “a more absolute intention,” something better for mankind, “the luminous reality concealed behind the veil of experience.” Robinson articulates beautifully how trials of character, the body-blows of injustice, can descend in front of any hope like a blinding smoke on the field of war.

Tough times require perspective. The fact of things being a certain way doesn’t automatically mean that they should be so. This called the fact-value distinction, and it helps keep the bigger picture of God’s ultimate renewal of creation in view. In spite of appearances, dire as they can be, God assures his people, “I know the plans I have for you, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future” (Jeremiah 29: 11). That such is made possible through Jesus is the Christian gospel.

Credo, Credimus

Back to the film. Arthur’s descent into homicidal insanity traces its roots not only to medical and socioeconomic influences but also derives from a nihilistic, “I don’t believe in anything,” outlook. The setting of Joker is emblematic of this poisonous attitude. A vast urban sprawl that strips individuals of their moral vision is an ideal spawning ground for a villain like the Joker.

After all, in a society with no moral code, “Why does anybody do anything?” If there is no hope of a coming kingdom, neither is there any reason to live in anticipation of such a possibility through good ethics. Anything goes; the weeds of moral decay germinate without relent.

In the postmodern hell-scape of Gotham City, all meaning is artificially constructed and always changeable. The creeds, however, call a halt on the production line of manufactured ideals by putting us in touch with our Christian heritage. In stark opposition to this communion with our forebears, Joker presents an ahistorical nowheresville.

The film’s opening line, “The news never ends,” is demonstrative of this point. A media-saturated, up-to-the-minute urban wasteland has no time for the thinkers and prophets of old times; it’s too busy pleasuring its originality fetish.

As the Joker surmises, addressing a talk-show audience, “All of you, the system that knows so much, you decide what’s right or wrong, the same way that you decide what’s funny, or not.” Arthur’s galling spate of murders quite simply carries this principle, the moral relativism of any postmodern society, to its logical conclusion. Having abandoned every time-honored system of right and wrong in favor of an ad hoc moral approach, Gotham has disarmed itself also of the ability to condemn the Joker. If all moral systems are equal, a life of heinous crime is legitimate.

For me, Joker is — in part, at least — a cautionary tale against abandoning fundamental principles, or even attempting to replace them. As Christians, we rise together to say the creeds as part of our worship. We hold our beliefs both individually (“I believe,” in the Apostles’ Creed) and communally (“we believe,” in the Nicene Creed). Whereas Joker’s world of urban isolation admits of only individual belief, Christians maintain a complimentary second layer: those convictions that we share in common.

Arthur, by now very much transformed into the Joker, complains, “Nobody thinks what it’s like to be the other guy.” Even if someone, maybe one of the few sympathetic characters, were to make an effort, alas, our antihero lives in a world where life-giving conversation is a practical impossibility.

Shared accounts of God’s work in the world and our place within it — the creeds, and all the theological and artistic riches they inspire — enable us to express our hopes and fears through a network of religious concepts. We have a flexible framework with which to begin. Arthur, by contrast, withers in silence until it’s too late. With no communal belief-language to make sense of his existential angst, his inner demons finally consume him.

Only now, when it’s disappearing, has it become clear what we’ve given up. Like the citizens of Gotham, our postmodern world is lacking a shared understanding of what life is for. Christians can defy this crisis of meaning by confessing the creeds with heart and soul, bringing the language of religious faith into conversation with everyday challenges, and having a bit more courage in our convictions. At the end of the day, “faith is confidence in what we hope for.”