The Kingdom of God: Jesus challenged the kingdoms of this world ceaselessly with his provocative What Ifs about our world. Don’t like the powers that be? What if God were the ruler here? Tired of news about murder, hopelessness, angry young men choosing to be terrorists? What if this were God’s kingdom? Angry about your taxes? What if God, not Caesar, were asking you to cough up – what would it cost you then?

The Kingdom of God: Jesus challenged the kingdoms of this world ceaselessly with his provocative What Ifs about our world. Don’t like the powers that be? What if God were the ruler here? Tired of news about murder, hopelessness, angry young men choosing to be terrorists? What if this were God’s kingdom? Angry about your taxes? What if God, not Caesar, were asking you to cough up – what would it cost you then?

What if a man were lying, beaten, by the side of the road, and you came along . . .What if a sheep were lost . . . or a coin? What if a guy who hadn’t gone to church in donkey’s years, and whose work was pretty shady, went to synagogue one day to pray? What ifsomeone took good seed and scattered it everywhere?

God, Jesus could make you think about everything! And he could stop you from thinking about your resentments, could stop all the complaining all of us do, the ceaseless whining of grown-ups about how the world is going to hell. His What Ifs were about the world becoming heaven: God’s kingdom.

He didn’t start a protest movement, he started a here- on-earth- God-with-us movement. He didn’t start a political movement. But everything he said and did had political implications. He deliberately used kingdom language, knowing he was challenging the other kingdoms, Caesar and Pilate’s, Herod’s, the class system of the Temple, provoking anger and delight.

If Jesus had wanted to avoid the political connotations of kingdom language, he could have. He could have spoken about the family of God, or the people of God, or the community of God, or the kinship of God. But he didn’t, he talked about what life on earth would be like if God were King rather than the rulers people knew. (Marcus Borg, in Convictions).

On Palm Sunday Jesus sharpened the contrast: he staged a Kingdom of Heaven entry into Jerusalem, in direct contrast to the frequent processional entries into the city by the battalions of Rome.

A few days later, he overthrew the tables of the money-changers and sellers of substitutionary offerings (animals to be sacrificed) in the temple.

The authorities had had enough. They tried to discredit him in public debate, but he was too skillful for that. Shall we pay taxes to Caesar, they asked, and it was a trap, for if he said No, they would arrest him right there, and if he said Yes he would be sanctioning their oppression. His asked them whose image was on the money. And of course it was Caesar’s. And they all knew the Ten Commandments, that God wants no graven images. Jesus tells them to give those images to Caesar. But what is God’s (their images, their lives) belongs to God. What is key here is that Jesus eluded their snare. He did not tell them to pay Caesar. Instead, he talked about images and loyalty.

Then a betrayer told the authorities where he was staying. They arrested him at night, without a public outcry. All the ensuing details, the trial by the city councillors, the conversation with Herod, the scourging and the crown of thorns, the conversation with Pilate, the cross, all show how these authorities, whose power was publicly vested in God’s name, are unholy, for all of them are saying No, saying No over and over, saying No singly and collectively, to the kingdom of God.

Then a betrayer told the authorities where he was staying. They arrested him at night, without a public outcry. All the ensuing details, the trial by the city councillors, the conversation with Herod, the scourging and the crown of thorns, the conversation with Pilate, the cross, all show how these authorities, whose power was publicly vested in God’s name, are unholy, for all of them are saying No, saying No over and over, saying No singly and collectively, to the kingdom of God.

Good Friday is the loudest No to God in the Bible. It is not the only No to God in scripture, but it is the most deafening, door-slamming No. It is a public No to God said by the principalities and powers of this world, a No that lives forever in human history.

Some say Jesus chose this and some say God chose it for him. Some say Jesus suffered and died as a kind of payment (an atonement, a redeeming) for all our unholy Nos to God. Some say Jesus was born to die this death, it was his main purpose. All these are familiar ideas. But not all serve the idea of the Kingdom of God here on earth.

Marcus Borg notes that all the gospels anticipate Jesus’ execution early in their narratives, but none of them teaches that his death was payment for sin. And neither does Paul say this , though the cross and Christ crucified are central in his writings. The gospels are an anti-imperial vision of what the world should look like. As are Paul’s letters. The cross is an accusation against the imperial powers.

Calling Jesus’ crucifixion a choice is a misunderstanding. When we look at some Christians who have incurred death through teac hing and acting as Christ did, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King Jr., and Oscar Romero, we can see that they did not want to die, but they did understand they were taking risks that could lead to death.

hing and acting as Christ did, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King Jr., and Oscar Romero, we can see that they did not want to die, but they did understand they were taking risks that could lead to death.

The importance of their proclamation of a different vision of the world led them to believe taking those risks was worthwhile. Bonhoeffer opposed the Third Reich and Hitler with the vision of the kingdom of God. King opposed racism and segregation in America with the same vision. And Romero opposed the brutally violent dictatorship of El Salvador with that vision. Each of them was transformed in their understanding of what their own life meant by internalizing Jesus’ vision of a world that was for all, a vision that can transform everyone’s life. It is not death they chose, it is not death that Jesus chose, but life, with God, here on earth.

Thank God, the story does not end with crucifixion.

__________________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Jesus Entering Jerusalem – detail. Parish Church of Zirl, Austria. Mural. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. A Sower Went Out to Sow, mosaic in Brasov, Romania. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. The Arrest of Jesus (Judas’ Kiss) by Giotto. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

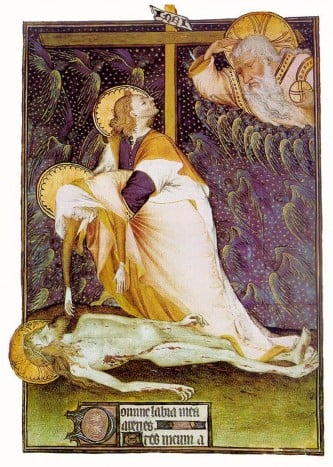

7. John and Mary in Lamention After the Crucifixion. c.1430, from Heures de Rohan, by The Rohan Master, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition