The numbers are staggering. It boggles the mind – a terribly British, pretty formulaic, Edwardian era manners drama has become the most watched television show in the world. (Well, excluding soccer). And I do mean the world.

The numbers are staggering. It boggles the mind – a terribly British, pretty formulaic, Edwardian era manners drama has become the most watched television show in the world. (Well, excluding soccer). And I do mean the world.

In 2012, while escaping it all on a cycling trip in Cambodia, Jim Carter, who plays the Carson the butler, found himself amid the ancient temples of Angkor Wat, wilting in the steamy climate — and suddenly swarmed by a group of Asian tourists screaming, “Mr. Carson!”

According to the New York Times, which reported this vignette, the show was likewise a hit in Sweden, Russia, South Korea, the Middle East, Denmark, Netherlands, Italy, Australia, Norway, Belgium, Israel and Iceland,and dozens of other locales where viewers wouldn’t know a dowager from a dogsbody.

“I was in Shanghai earlier this year and people were coming up to me saying it was their favorite show,” the Times quoted Gareth Neame, who came up with the initial idea for the series. “(Shanghai) is the People’s Republic of China, and (Downton) is a show about primogeniture and inheritance and aristocracy and all those things that you thought the whole point of China was to do away with. So that was a surprise.”(1)

And the question is, why? What is drawing people to this series? A lot of conjecturing has been going, and a lot of reasons put forth. Some of them can’t be real – eye-candy, for instance, which Downton certainly has, if you like old manor houses and Edwardian clothes on pretty women and men. But the world is full of eye-candy, why this show?

Two reasons put forward by several reviewers, that seem real to me are: the confusion and tension about class, which is part of every show, and is also part of our own lives, though, in democracies, we are never allowed to talk about it. In Downton, class is always present, and undergoing much change, from social upheavals, like WWI, which brought seismic shifts to the economy of Britian, increased experience to those who fought and those who stayed at home and kept the country going, especially women. All of this is seen through personal stories, which is just the way we experience class, every day, in our own lives.

Two reasons put forward by several reviewers, that seem real to me are: the confusion and tension about class, which is part of every show, and is also part of our own lives, though, in democracies, we are never allowed to talk about it. In Downton, class is always present, and undergoing much change, from social upheavals, like WWI, which brought seismic shifts to the economy of Britian, increased experience to those who fought and those who stayed at home and kept the country going, especially women. All of this is seen through personal stories, which is just the way we experience class, every day, in our own lives.

And the second reason is love stories. They are woven into every one’s story in Downton, as marriages, courtships, flirtations, or unrequited loves, so very many unrequited loves – and even in the requited ones, the course of true love never runs smooth.(2) There are women’s stories (and for a period drama Downton has an amazing number of women) and men’s tales, tales of illicit love and good and bad marriages, cads, bounders, who are mostly survived, but leave some broken lives in their wake. Our hearts rise to them all.

Julian Fellowes, the writer of Downton, has an amazing gift for seeing how love plays in lives on many social levels, in ultra-conservative stalwarts like Carson, the butler, and in free spirits like Rose, the Earl’s ward and relation, who has a brief fling with an American black jazz musician, and the Dowager, who is outwardly as conservative as Carson but is slowly revealed to have had at least one daring liaison in her past.

In all of this, Fellowes reveals layers of our emotions, often rumored but seldom shown clearly. Some critics deride this as Soap Opera, but the soaps (which have never gone global and which I find dull) do not reveal feelings at all – they center solely on reactions. Downton, unlike most dramas, brings emotion into the foreground.

In all of this, Fellowes reveals layers of our emotions, often rumored but seldom shown clearly. Some critics deride this as Soap Opera, but the soaps (which have never gone global and which I find dull) do not reveal feelings at all – they center solely on reactions. Downton, unlike most dramas, brings emotion into the foreground.

But class and emotion, vital as they are, are not enough to account for the pull Downton has had on the world in our day. Julian Fellowes, in an interview for Masterpiece, was asked about being the sole writer, very unusual in today’s world of script writing teams. Fellowes said that they tried to bring in other writers in the second season. But somehow the show itself ‘had a voice’, he said, and lost it when others took part in the writing.

‘The Voice’ of Downton is Fellowes’ voice. And of his own voice, Fellowes has said more than once, it is his fundamental conviction that all peoples’ lives matter, different as their circumstances may be, different as their places in the world may be, different as their daily work is, still, all peoples’ lives matter.

We feel his deep caring in each character. Despite our own desire, even our insistence, to try to divide them into good and bad, heroes and villains, they are not divided into more and less human. Moral and immoral, small-minded and generous, priggish and free-thinking, compassionate and judgmental, even kind and unkind, all of them are all of these.

Oh, some are more often one thing than another, but all have their regrettable faults, and all have their fineness. The Dowager, most adored of all, is often dreadful, but then also, surprisingly, compassionate. The complicated and often nasty servant Thomas, has been broken by circumstance and we have shared his tears. The bitter and scheming O’Brien had her lingering remorse, and left to pursue a dream for which she had a sudden chance.

Oh, some are more often one thing than another, but all have their regrettable faults, and all have their fineness. The Dowager, most adored of all, is often dreadful, but then also, surprisingly, compassionate. The complicated and often nasty servant Thomas, has been broken by circumstance and we have shared his tears. The bitter and scheming O’Brien had her lingering remorse, and left to pursue a dream for which she had a sudden chance.

Over the years we have come to learn that all of them are cherished. Our expectations for wrath, punishment, even come-uppance, have slowly fallen away, as the steadfast caring of Julian Fellowes for all the people of Downton has been an unwavering light. When we tune in, we know that if their lives matter, then so may ours.

In Downton, a place where people seldom go to church, and where the vicar has been a rather narrow-minded fellow on at least two occasions, the presence of a lasting, even a holy love has been constant and deeply affecting. It is this which draws us, in our times, which are so often brutal, seismically shifting, and violent. Downton affirms us: whatever happens, we will not fall outside the grace and love of of its creator, nor will we fall outside the grace and love of ours.

__________________________________________________________________

1. New York Times article by Jeremy Egner, Jan 3, 2013

2. Unrequited Loves: because two friends have said they cannot think of more than one of these, I am making a list of the ones I recall: Daisy for Alfred; Alfred for Ivy; Barrow for James; Lord Gillingham for Lady Mary; Lady Edith for Strallan, who left her at the altar; the schoolteacher, Miss Bunting, for Branson; Ethel Parks, the maid, for a young wounded officer who left her pregnant; Jack Ross for Lady Rose; the Russian prince for the Dowager; Lord Merton for Isobel Crawley; Dr. Clarkson for Isobel Crawley; Mrs. Patmore for the butcher who turned out to be a rat; the art expert for Lady Crawley. And in truth, I think, the farmer’s wife for Marigold, whom she is forced to give back to Lady Edith.

Illustrations:

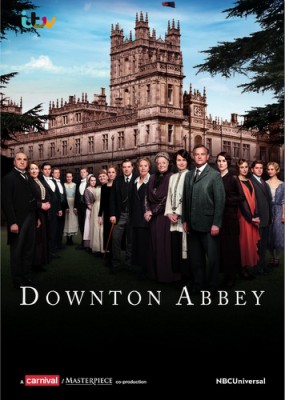

1. Downton Abbey poster, Series 4.

2. Downton Abbey poster, series 6

3. Downton Abbey poster, Carson and Mrs. Hughes at the beach.

4. Downton Abbey poster, Anna and Bates, lady’s maid and valet.

5. Downton Abbey poster, Mrs. Hughes, the housekeeper.

6. Downton Abbey poster, Mrs. Patmore, the cook

7. Downton Abbey poster, Daisy, former scullery maid, now assistant to Mrs. Patmore.

8. Julian Fellowes, writer, Downton Abbey. His Wikipedia page image.