Easter is a head-scratcher, so What’s Up is a perplexing question. And Easter has so many possible answers, it’s a perennial question.

Between the four gospels, there are twelve Easter encounters – and no two of them are alike – making the puzzle more complex.

The one thing all twelve stories have in common is – no one was able to recognize Jesus right away.

And that’s a big help, really. You can rattle on about amazement all you like, but we do recognize people we are amazed to see when we see them. So the evidence is pretty clear that Jesus didn’t look the same. This is huge, the realization that no one comes Up after being that far Down without being significantly changed. So don’t expect a recognizable Jesus to appear anytime soon. Instead, expect to meet the Risen One in someone who seems to be a stranger.

Easter recognition comes in a variety of ways, depending on the disciple mostly, also depending on where it happens. At the tomb, for Peter, it was folded grave clothes that were convincing. For Mary, it was hearing her name come from his lips. After walking all day and talking with him, it was seeing him break bread at Emmaus that convinced James. On the beach, after a night’s labor catching nothing, it was the seine straining with fish that convinced Peter. For Thomas, it took touching the wounds, but for the others in the Upper Room, watching Jesus eat was the convincing thing.

Perhaps the point of all of this is that we don’t all have to discover Easter in the same way. Or at the same time. And in any given group of us, we will each experience our own mix of wild joy and major misgivings, and each ask our own questions.

The Aha Moments arrive sooner or later, but never on demand.

There are no wrong answers to the Easter question, What’s Up?

Easter is a Question. It is not, and never has been, a doctrine. Or a definition. Or a snapshot. Besides Jesus not being recognizable, the other common element in the Easter tales is this: all the amazed disciples were brimful of questions.

The questions brought them to the tomb, to the Upper Room to mull over the reports of those who had gone to the tomb, to the Inn at Emmaus, and to the beach where they fished in confusion and without answers till Jesus prepared them breakfast.

Easter rises from a cradle of questions. Each disciple sees, hears, touches it differently. Each stammering report raises more questions. In the abundance of questions, there’s room for more Rising. The questions act like yeast in the lives of those who stumble upon Easter.

There’s one question, though, that befouls Easter, because it takes us in entirely the wrong direction. Sadly, it is an all-too-common one, beguiling in its seeming reasonability. That question? It’s Who Killed Jesus?

The delusion is that this question has a clear answer. And so often, when we are uncomfortable with talk about an Easter Rising, we turn instead to the question, Who’s Guilty here? A thousand fingers can point in a thousand different directions, and we will never have a clear answer. The fingering will never be finished.

Who would you name? Herod? Pilate? The soldiers who drove in the nails? The one who used the spear to finish him? Caiaphas? The Sanhedrin? The mob who called for Barrabas to be spared? The rest of the city, letting this happen? Judas, for that betraying kiss?

What about Caesar, who put Pilate in charge and Herod on that puppet throne? Or what about God? Shall we say that God planned this? Or allowed it? If we place the blame on God, isn’t this blasphemy?

Why does that old canard, The Jews Killed Jesus, remain alive among us? The crucifixion fields were filled with Jews, hung on crosses by Roman soldiers. Jesus was one of those Jews.

Everyone who wept for Jesus was a Jew. Neither he nor they ever left off being Jewish. He was still a Jew on Easter.

Outside of a relatively small circle of folks in Jerusalem, no one else in all Israel knew about the death of the man called Jesus. And outside of the even smaller circle of his disciples and friends, his brothers and his mother, no one knew of Jesus’ Easter Rising.

The dark side of human nature, what we, at our worst, can do, is always present among us. Delving into that dark side is an important learning about being human. But it will not help us discover Easter, and it will not help us learn what the divine power of Love can do.

It is not as if this were a tale of a terrible injustice that needs to be addressed in court somewhere. Easter is a tale of the lasting power of love, the resilience of life itself, the strength of hope, and the unbreakable bond that unites people who love lastingly, to God who loves eternally.

The way to Easter winds among people who have glimmers of hope, occasional rippling laughter even in the midst of tears, and courage even when they are afraid. Peter may have run away, but he didn’t hide for long. The way to Easter lies among people who share life together, and bread, and loss, and how they collapse under pressure and how they rise again.

Gathering together will yeast the lifting of our hearts, and our recognition that the Lord is here. Easter is more contagious than terror. Hope, kindness, forgiveness, understanding, all these things, can spread among us when we share them with each other, and when we share the question we are all asking: What’s Up? Can there possibly be joy in this sorrow? Light in this darkness? An absence of death in the midst of our mortal fear? Without answers to these questions, but without despair, we gather and we shout them out: Christ Is Risen! Even if we have no idea what that could possibly mean, we shout Alleluia! And then Easter appears.

_________________________________________________________________

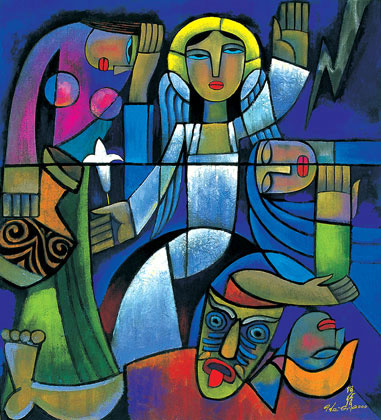

Image: Easter Morning, by He Qi, 2001, Nanjing China. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.