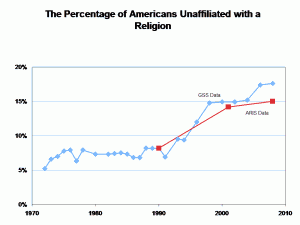

In the 1990s, a seismic shift occurred in religious America. During that period, the percentage of Americans who did not affiliate with any religion more than doubled. In the 1980s, about 7% of Americans reported being religiously unaffiliated, and by 2000, this was up to 14% (and has since increased to about 17%). To be clear, many of these religiously unaffiliated still believe in God, but they don’t associate with any particular religion or denomination.

What happened, and why did it happen in the 1990s? Micheal Hout and Claude Fischer, sociologists at Berkeley, published a study that links part of this substantial drop of religious affiliation to politics. They examined what type of people left religion in the 1990s, and they found it closely tied to political beliefs. Unaffiliation among liberals increased 11 percentile points; among political moderates it increased 5-6 points; and among political conservatives it increased an insignificant 1.7 points.

So, why would liberal or moderate politics move people away from Christianity in the 1990s? Well, that was a time in which the Religious Right held considerable sway in American politics, and the linkage of a Republican agenda to Christianity served to politicize Christianity. This repelled people who accepted Christianity but not the Republican party. As a result, many people who would otherwise affiliate with Christianity perhaps moved away from it as a reaction against this Christian-Republican linkage. Hout and Fischer summarize:

Our conjecture is that the growing connection made in the press and in the Congress between Republicans and Christian evangelicals may have led Americans with moderate and liberal political views to express their distance from the Religious Right by saying they prefer no religion.

(I’ve had the chance to correspond with Michael Hout on this issue, and in more recent work, he has found that the reaction to the religious right started even earlier, in the mid-1980s, when the Religious Right was becoming well-known).

How much of an effect did the politicization of Christianity have? A very large effect. Hout and Fischer estimate that more than half of the people who disaffiliated from religion in the 1990s did so out of political concerns. As such, had American Christianity not become so politicized, the percentage of Americans preferring not to affiliate with religion would have risen only 3 or 4 percentage points instead of 7 points.

To appreciate the magnitude of this effect, let’s put some numbers to it. In 1990, there were about 250 million adults in United States, and let’s say that three-quarters of them were Christians. This gives us 187 million Christian adults. If 3.5% of them turned away from their faith due to the politicization of religion, that works out to be 6.5 million Christian adults lost in the 1990s due to politics.

This is a big number—a really, really big number. It appears that the work of the Religious Right—which was intended to advance the Kingdom—actually lost over 6 million Christians in the 1990s. Assuming that these unaffiliated adults in turn raised their children differently as a result of pulling away from Christianity, it’s entirely likely that we would have 10 million more Christians in America today had it not been for the previous work of the Religious Right.

Hout and Fischer found that the people who left Christianity in reaction to conservative politics were, on average, less committed than those who stayed, but this is not grounds for nonchalance. Many of those who left were committed to their faith, they just had very strong feelings about politics. Even for those who were less committed, it seems easier to reach them when they are already sometimes attending church and peripherally involved in the faith than when they disengage altogether, and so that too is a lose.

Politicizing Christianity in the liberal direction is also problematic. From personal experience, I have observed that churches or denominations that affiliate with politics to the Left lose many of their more-conservative members and the vitality that they bring to the faith. This fits with the conventional wisdom that the liberalization of Mainline Protestant churches has lost them considerable share in their religious marketplace. Based on data from the General Social Survey (which asks respondents in which religion they were raised), I estimate that in 1920, over 40% of Americans affiliated with a Mainline Protestant denomination. Now, that is down to less than 15%. Undoubtedly there are multiple factors undergirding this decline, but it seems reasonable to assume that liberal politics played a part.

Last week I posted my own thoughts about religion and politics. Perhaps some overlap between religion and politics is inevitable, and maybe even good can arise from it. I have little to add to how this should be done other than to point out that when we link our faith with a particular brand of politics, we will probably lose many believers.

Thanks Tim for the input!