By John Schmalzbauer, Missouri State University

Since last September, Sojourners has explored the meaning of “evangelical.” Such conversations have supplemented more academic analyses by political scientists and sociologists.

After spending so much time on evangelicalism, it’s only fair to ask about American Protestantism’s other major tradition, the Protestant mainline.

In the judgment of Martin Marty, the term “mainline was and is used mainly by enemies of the mainline.” Unlike evangelical, it is a relatively recent word. Often used to designate moderate-to-liberal Protestants, its history is shrouded in mystery.

Just where did the expression “mainline Protestant” originate? In a fascinating paper delivered at the 2008 American Society of Church History meetings, Elesha Coffman traced the genealogy of the mainline moniker. Her investigations led her to the main-line suburbs of Philadelphia, where the Pennsylvania Railroad connected wealthy elites to Philly’s urban core. This is the neighborhood explored by patrician sociologist E. Digby Baltzell in The Protestant Establishment and Philadelphia Gentlemen.

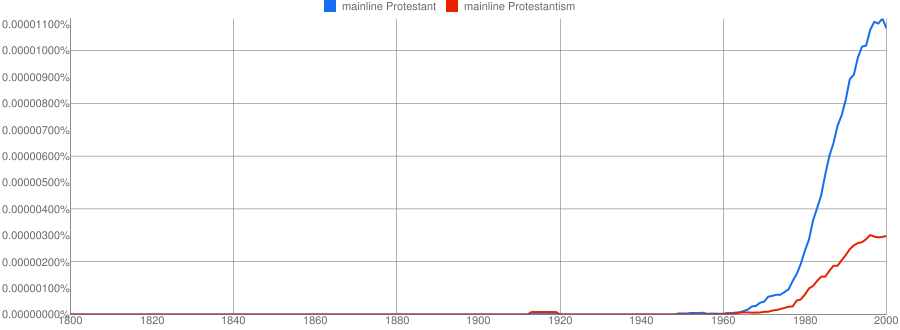

When Coffman delivered her paper, Google Culturomics was just a glimmer in the eyes of its Mountain View, California creators. Four years later, it is now possible to trace the use of term over the past couple centuries. As this graph shows, the labels “mainline Protestant” and “mainline Protestantism” seldom appeared before the 1960s. Both surged in popularity during the 1980s and 1990s.

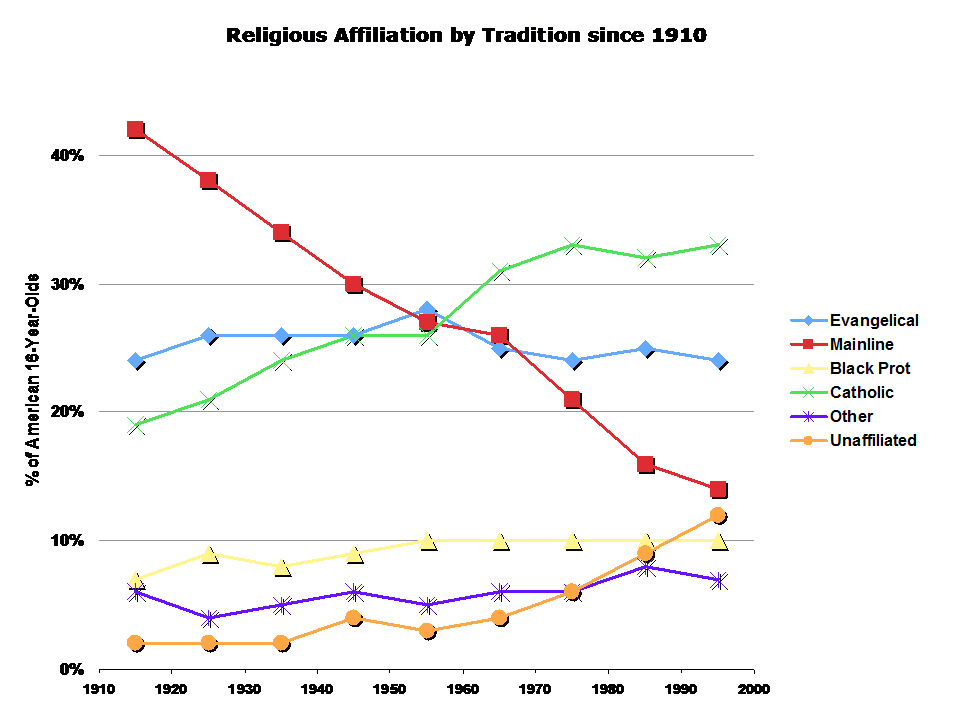

Ironically, this period coincides with the numerical decline of the mainline denominations. Since the 1960s, the “seven sisters” (the Episcopal Church USA, Presbyterian Church USA, United Methodist Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, United Church of Christ, American Baptist Churches, and Disciples of Christ)have suffered dramatic losses in membership. For a striking contrast, compare the figure above with a graph of the plunging market share of mainline churches.

How to explain this strange juxtaposition? In an invaluable essay, Louisville Institute director James Lewis notes that most of the literature on the mainline has focused on two questions: “1) just how bad is it and 2) how did we get here?” Whether penned by friends or enemies, writing about mainline Protestants has emphasized the theme of declension. By defining the mainline as a problem, this scholarship has contributed to the rise of a new label. Whether such terminology can contribute to mainline Protestant renewal is anyone’s guess. One thing seems certain. This episode illustrates the “stickiness of labels.”