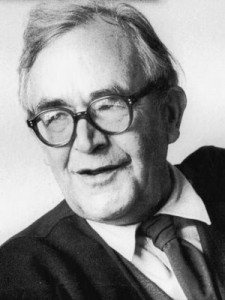

Karl Barth’s theology and exegesis is often debated. I love him in places, I disagree with him in places. I agree with others’ exegesis of his exegesis, I disagree with others’ views on him. But one thing we should all appreciate is his ability to synthesize theology and exegesis in such a way that even when there is disagreement with him, the counterargument had better eat its Wheaties before coming to the table.

Paul McGlasson rightly lamented that Karl Barth’s exegesis in his magnum opus, Church Dogmatics (CD), has not only been misunderstood and/or maligned, but also straight up neglected by scholars. In his opinion, this is a result of Barth’s theological-exegetical method, a blend of biblical theology and systematic theology that scholars in neither field wish to tackle. He concludes:

“The result is that, for scholars of theology, the work is too ‘biblical,’ while for scholars of the Bible the work is too ‘theological.’ The resulting fate of Barth’s biblical exegesis is in a way not really surprising. At least part of Barth’s reason for doing extended biblical exegesis in the context of Christian theology was to wage a direct assault on the bifurcation of scholarly work into two such separated disciplines. Theology, for Barth, should again be biblical in a technical, disciplined sense, and likewise should study of the Bible be disciplined by confessional theological concerns. The immediate result of this assault on the bifurcation of theological disciplines was that at least this part of Barth’s work simply attracted no scholarly attention.”[1]

Indeed, Barth was a rigorous exegete both in his commentaries, his other writings, and in CD. However, this did not come without keen theological insights and overtones. He was a rare hybrid whose method was not entirely hermeneutical nor entirely theological. He was a confessional theologian, with a heavy focus on Christ as he exegeted Scripture. If Christ was and is the point of God’s revelation, then he can be seen everywhere in the canon.

In the end, then, Christ becomes the overwhelmingly central point of both theology and exegesis, making the two inseparable for Barth.

Revelation and the Word of God

For Barth, Scripture is “one long celebration of the fact that God speaks, and that as God speaks he opens himself up to us, giving us a share in his life through Christ and the Spirit.”[2] He put it this way: “God gives himself entirely to man in his revelation, but not in such a way as to make himself man’s prisoner. He remains free in his working, in giving himself.”[3] This divine speech is the lead component for understanding Barth’s views on revelation. For him, knowing God is, in short, unattainable. The unattainable is only attainable by God’s self-revelation, a freely chosen action in no way dependent upon man.

God’s Word can only be attributed to God himself as a witness to himself, not in historical formulations or provable assertions concerned with precise correspondence.[4] For if man could simply “prove” the truth of God’s revelation by some scientific method, there would be no need for faith. Faith accepts the claims of Scripture that seem unbelievable to the arrogant human mind.[5]

The Trinity plays a fundamental role in Barth’s doctrine of revelation. Joseph Mangina defines it as a threefold conviction:

“First, God is always prior, always Subject in his relation to creatures; God’s revelation is identical with his lordship. Second, the actual content of revelation is Christological: ‘Revelation in fact does not differ from the person of Jesus Christ nor from the reconciliation accomplished in him.’ … Third, revelation does not render human beings passive, but engages them in a self-involving way as knowers, subjects, agents. It makes little sense to speak of God’s self-unveiling unless there is someone there to receive it. Think these convictions together, and one arrives at the doctrine of the Trinity.”[6]

Barth’s emphasis on the Trinity answers several of the theological problems many scholars face. The Trinity allows one to see Scripture as a coherent whole, and it shows how God relates to his creation—that the world was made in and for Christ, and man lives through Christ and the Holy Spirit. The Trinity answers who God is and Scripture shows what he says and what happens when he speaks. Since God has self-revealed himself at Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, revelation has a trinitarian shape.[7] The further implication, then, is that Scripture is uniquely divine.[8]

As an outflow from this trinitarian focus, Barth believed theology and exegesis should be done for the Church, and Christ is the Church’s head. He is the center of everything. So Scripture is not about the text itself, or the writers thereof; it is about Christ, the “revealed” Word of God. He argued that the reader does not come to Scripture to attain the aforementioned scientifically verifiable truth claims; rather, one comes to the text seeking Jesus Christ and Scripture’s unified witness to him.[9]

The word witness is paramount to understanding Barth’s doctrine of revelation; Scripture is the authoritative witness to God’s revelation, not revelation all by itself. For Barth, historical-critical methods place needless limitations on the reader and fail to answer real questions about God; Barth’s method reveals the Trinitarian God, the object of revelation and worship.

Finally, the Holy Spirit allows the reader to hear God’s words. He brings the reader and the triune God together. As Magina says, “the hearer of the Word’ is a crucial element in the “trinitarian event” of revelation for Barth. The Holy Spirit sets a person free to participate in this event through a “subjective reality” and by pointing him to the triune God.[10] While Christ’s authority implies Scripture’s authority (as an attestation to him), the Holy Spirit guides believers under the indirect, mediate authority of the Church through norms such as canon, creeds, and confessions.[11]

As one begins to read Barth’s handling of OT texts, one notices this tremendously God-driven understanding of revelation. The OT is not a time-contained history of early Jewish community. Rather, the OT has a meta-message that combined with the NT is fully revealed and realized in Jesus Christ.

Barth and the Old Testament

As we’ve discussed thus far, Christ is the central component to Barth’s theological-exegetical method. His method is, in a sense, a hyper-Christological hybrid of theological and hermeneutical methods. He saw Christ as the key to seeing Scripture as a whole. He was less concerned with the text and its unique peculiarities, and more concerned with encountering and contacting the divine reality.

So whether OT or NT, the revelation of God revealed in Jesus was the point.[12] Whatever God does, Jesus Christ is the means. Christ, in fact, holds the entire canon together. The OT and NT were inseparable for Barth:

“The Old Testament is not an introduction to the real New Testament Bible, which we can dispense with or replace. We cannot eliminate the Old Testament or substitute for it the records of the early religious history of other peoples, as R. Wilhelm has suggested in the case of China, B. Gutmann in some sense in that of Africa, and many recent fools in the case of Germany. If we do, we are not merely opposing a questionable accessory, but the very institution and existence of the Christian Church. We are founding a new Church, which is not a Christian Church. For not only is the canonicity of the Old Testament no arbitrary expansion of the evangelical-apostolic witness to Christ… Whether we like it or not, the Christ of the New Testament is the Christ of the Old Testament, the Christ of Israel. The man who will not accept this merely shows in fact he has already substituted another Christ for the Christ of the New Testament.”[13]

Roger Keller clarifies Barth’s view: “As [the OT] was coordinated with Christ, it became a witness of him in expectation, thereby being revelation in expectation.” [14] The OT represents the expectation of the coming Christ. Since the OT awaits his coming, the content within is Christological, the same as the content of the NT. Christ was present with the OT people through that hope.[15]

In Barth’s mind, although the OT does not directly mention Jesus Christ—for he was not yet incarnated—he is prefigured comprehensively in the pages of the OT. The various people and events in the OT are recapitulations of this theme.[16] The NT writers were “utterly unanimous” in seeing the OT as the “connecting point for their proclamation, doctrine and narrative of Christ … the fulfillment of the Holy Scripture read in the synagogue.”[17] Keller further shows three basic ways in which Barth saw Christ holding the OT and NT together.

First, both witness to revelation. “The OT bears witness to God’s free actions in relation to humanity,” Keller explains, so “when the OT talks of the togetherness of God and human beings, it is speaking of revelation.”[18] And when God uses humans as instruments in the OT, this is proof that the OT is pointing to Christ. Through humans such as the priests, kings, and prophets, no human instrument fully expresses God with mankind.

Enter Jesus, Immanuel, “God with us;” God assumed human form to complete his covenant.[19] More on this later, but when “God’s mercy and judgment were seen among human beings through such OT figures, Jesus Christ was already the content and theme of the OT covenant.”[20]

Second, the OT witnesses to the hidden God. Barth argued that “to the eyes of the world, God was hidden in the incarnation and the cross, but in that very hiddenness, he was revealed to the eyes of faith.”[21] Crucial to Barth’s connecting the OT and NT is that though Christ was not yet incarnate and known to Israel, he was nonetheless present in their victories and sufferings.

Once the reader then comes to the full canon, faith allows him to see what was once hidden: Christ’s saturation of all of Scripture. This leads to the final way in which Christ affixes the OT and NT.

Third, God is both present and coming in the OT. The eschatological hope in the OT that God’s covenant with Israel would one day be fulfilled beyond the scope of the OT story.[22] The prophets, the kings, the temple, the land, and the numerous other aspects of Israel’s story are shadows of Christ in different ways, all adding up to the entirety of Israel’s history and thus, the entirety of Christ.

So it is only through faith that one can grasp this knowledge and see its fulfillment in Scripture.[23] The NT writers saw this by faith, and the hiddenness of God in the OT and NT still comes to light today through the eyes of faith. Keller closes:

“Of course, Israel and Christ are not identical [in Barth’s mind]. But one can say that in the history of Israel, in its singularity, there takes place the prophecy of Jesus Christ in its exact prefiguration. It is a true type and adequate pattern of him. The history of Israel, in the divine wisdom which controls its movements, is a foretelling of Christ. So it was, says Barth, that the NT understood the truth of Israel’s history to be Jesus Christ”[24]

For Barth, “The New Testament is concealed within the Old, and the Old Testament is revealed by the New.”[25] The OT was not merely a pre-Christ period of revelation, but rather fused with the NT in witness to him. “God’s covenant with man” was fulfilled in “God’s becoming a man.”[26]

The covenant in the OT was radically fulfilled by God himself in the incarnation. The “Wholly Other” stepped into human history, assumed human form, and fulfilled the covenant no human could fulfill. The OT points toward this over and again throughout Israel’s history.

Isaiah 53 as a Test Case

Remember, Barth saw the OT as part of this unified witness to the Word of God in the flesh, a forward-pointing expectation of the coming Christ. Christ = theology + exegesis. So when he came to passages such as Isaiah 53 and the suffering servant, he was unsurprisingly quick to highlight Christological aspects and move the critical concerns raised by other scholars to lesser priority.

Barth’s approach to Isaiah 53 was multi-layered. On the one hand, he appeared to be aware of the historical and critical issues surrounding the text. On the other hand, he also gave the impression that he was not overly concerned with these questions. In his groundbreaking work on Barth’s exegesis of Isaiah, Mark Gignilliat notes that Barth exhibited three different—yet ultimately complementary in his own mind—readings of Isaiah 53.

First, Barth focused on Jesus Christ’s identity as the suffering servant. God has revealed his glory from Heaven in self-communication with mankind, so this revelation alone allows the Christian to recognize the suffering servant as Christ; seeing him in the account is not a so-called “plain reading” of the text but is knowledge derived from faith. He further asserted that the passage is clearly speaking of Christ, “feeling no compulsion to justify such a claim.”[27] The suffering servant is Christ; Barth saw no need to qualify this statement with typological or allegorical explanations. As a confessional theologian, this is reasonable.

He also notes in CD that grasping the concept of Jesus as this suffering servant allows the Christian to appreciate the beauty of not only his exaltation, but his humiliation.[28] He is the Incarnate Word—both the risen Son of God of the eternally glorious Trinity, and a man with flesh and bones that suffered and died for mankind. This is eschatological promise of the suffering servant passage.

Second, Barth addressed the historical aspect of the text. While he never denied the historical or literary context of Isaiah, he was in the end not concerned with these issues. Other scholars wrestled over the actual identity of the servant (a real person in biblical times? Israel?), but Barth held that this only obscured the important matter of the text.[29] Remember, he was not exceedingly concerned with the eschatological identity of the servant—he had already definitively claimed that it is the prefigured Christ. That was the suffering servant’s chief identity.

Nonetheless, as noted, he did not want to completely deny the historical standing of the servant; instead, he simply posited that the servant fills the role of “God’s human partner in redemption.” So the OT affirms an historical figure while simultaneously affirming “the unique canonical role the servant plays as witness to an eschatological event that transcends its historical phenomenon.”[30] Barth wrapped it up this way:

“The question whether this partner, the servant of the Lord, is meant as collective Israel or as a single person—and if so, which? a historical? or an eschatological?—can never be settled, because probably it does not have to be answered either the one way or the other. This figure may well be both an individual and also the people, and both of them in a historical and also eschatological form.”[31]

Third, Barth expounded upon the suffering servant’s role within the broader context of the OT:

“[T]he history of Israel as a prophetic existence, embodied in all the contours found in Isaiah 53, uniquely prefigures Jesus Christ … So, in this sense, Isaiah 53’s servant is genuinely Israel and in another sense, genuinely Messianic because of the larger figural pattern of Israel as the exact prefiguration of Jesus Christ and Israel’s own history of failure.”[32]

For Barth, the suffering servant is a microcosm of Israel’s history. Israel consistently faced trials and tribulations throughout the OT. In his earthly ministry, Jesus would see the same troubles. Indeed, as noted in the previous section, “Jesus Christ incarnate is Israel incarnate embodying all of her hopes, frustrations, calling and failures” but, unlike Israel, he delivered on the faithfulness and obedience God had sought in his covenant people.[33]

Barth’s handling of the Isaiah 53 passage was paradigmatic of his theological-exegesis of the entire OT. He simply could not escape the Christological implications of the passage. Even when he dealt with historical-critical questions, he gave them an obligatory nod and then scurried on back to Christ. One could replace Isaiah 53 with other OT passages and find Barth employing the same method.

In this brief survey, Barth’s pervasive Christology is evident. Jesus Christ is the what of revelation; he reveals God’s Word in the flesh. Therefore, the OT is only truly revelation as it demonstrates and confirms the coming Christ. So one cannot, in Barth’s mind, read the text of Isaiah 53 and simply arrive at the notion that the suffering servant prefigures Christ. Christ brings that message to the foreground, even as the text is situated in history. The human then, by faith alone through the choice of God alone by the work of the Holy Spirit, comprehends the Christ-centered message. This is but a glimpse at what McGlasson called Barth’s “bifurcation of theological disciplines.” And it is helpful for those of us seeking to do theology and exegesis well.

———————

[1]Paul McGlasson, Jesus and Judas: Biblical Exegesis in Barth (Atlanta, GA: Scholar’s Press, 1991), 4 as quoted in Mark S. Gignilliat, Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel: Barth’s Theological Exegesis of Isaiah (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 2.

[2]Joseph L. Mangina, Karl Barth: Theologian of Christian Witness (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2004), 29.

[3]Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics [CD], ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance, (Edinburgh, UK: T&T Clark, 1956-1975), 1.1:371.

[4]Magina, Karl Barth, 43.

[5]David F. Ford, Barth and God’s Story: Biblical Narrative and the Theological Method of Karl Barth in the Church Dogmatics (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2008), 21-22.

[6]Mangina, Karl Barth, 36.

[7]Ibid., 37-38.

[8]Ford, Barth and God’s Story, 24.

[9]Mangina, Karl Barth, 43.

[10]Ibid., 44-45.

[11]Ibid., 46-47.

[12]John H. Hayes and Frederick Prussner, Old Testament Theology: Its History and Development (Atlanta, GA: John Knox, 1985), 272.

[13]Barth, CD, 1.2:488-89.

[14]Roger R. Keller, “Karl Barth’s Treatment of the Old Testament as Expectation,” AUSS 35, no. 2 (1997): 167.

[15]Ibid., 167-68.

[16]Gignilliat, Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel, 130.

[17]Barth, CD, 1.2:72.

[18]Keller, “Karl Barth’s Treatment of the Old Testament as Expectation,” 170.

[19]Ibid.

[20]Ibid., 171.

[21]Ibid., 171-72.

[22]Ibid., 173-74.

[23]Ibid., 175-76.

[24]Ibid., 177.

[25]Karl Barth, Evangelical Theology: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans: 1979), 28.

[26]Barth, CD, 1.2:103.

[27]Gignilliat, Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel, 125.

[28]Barth, CD 2.1:665.

[29]Gignilliat, Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel, 127.

[30]Ibid.

[31]Barth, CD 4.1:29 as quoted in Gignilliat, Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel, 126.

[32]Gignilliat, Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel, 130-31.

[33]Ibid., 131.