Anybody with an Instagram account has probably become aware of a social and cultural movement that is focussed upon the enabling of young people, in particular women, to take personal sovereignty over key facets of their lives. Described as ‘witchcraft’, with tags such as #witchesofinstagram, this is not spellcraft, charming or cursing as we have understood it in the past. Rather, it is a lifestyle movement that empowers the ‘witch’ to that personal sovereignty using such methods as power moves, styling and makeup tips, fashion and aesthetics, alongside spell work to enhance your life. As a lifestyle movement, this is a huge market and is removed from the esoteric and occult communities as we currently know them.

All of this is only interesting to a certain degree. However, it does give us pause to observe and consider our own witchcraft and, as these things often must, it impels us to regard those definitions we take for granted. Taking inventory is a good practice in and of itself, and it is part of the evolutionary process of our paths (if we are doing it right), with questioning being the fuel which drives us ever forward on this great adventure.

So what the hell IS witchcraft?

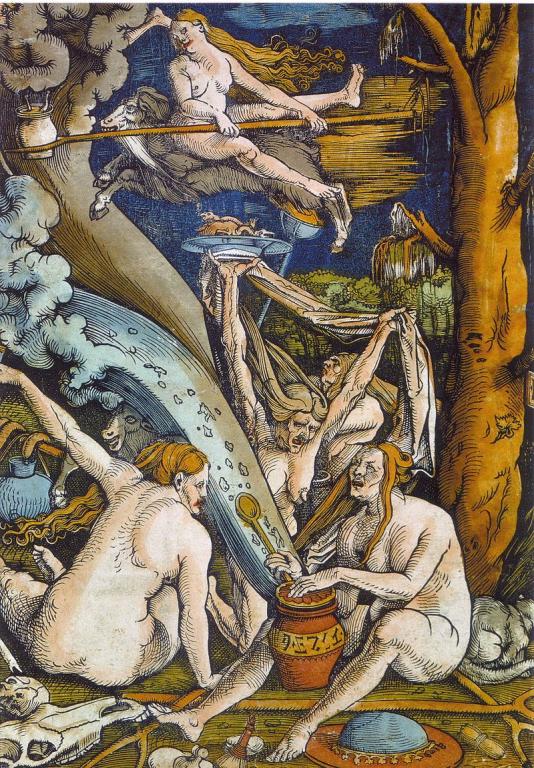

Running the risk of churning up ground already trod to dust beneath the feet of more worthy contributors, it is yet imperative to consider what we mean by witchcraft. In its original and most commonly used context, both contemporaneously and historically, it is used to identify those, especially women, who compact with the forces of evil and conspire to bring about the misfortunes of their neighbours. From this perspective, this is a complex and multifaceted definition which demands consideration of cultural circumstances surrounding the accounts in which the identification occurs. However, this has been the resounding and most consistent use of the term throughout human history, and remains an allegation levelled at individuals, often less fortunate, or otherwise singled out for persecution.

Draw The Witch’s Blood To Break The Curse

One example, which has been of particular interest and study to myself for nearly twenty years, relates to the exaggerated claims of one Mr James Hayward who in 1875, in the village of Long Compton, Warwickshire, attacked a 79 year old Ann Tennant with his pitchfork, stabbing at her legs. Unfortunately for both parties, one of the wounds punctured an artery in the elderly woman’s leg and she would soon die as a result. This is pertinent as, in 1945, another murder in the area by pitchfork was recorded and the case of witchcraft was determined by a crude comparison to that of Ann Tenant. The murder of Charles Walton, on Valentine’s Day 1945, drew the attention of luminaries as anthropologist Margaret Murray and Gerald Gardner, the ‘father of modern witchcraft’. Sadly, cursory research reveals that the similarity between the two murders is utterly far-fetched. However, it gives us a few things to consider in our understanding of witchcraft in its historical context.

Death Certificate received from J B Couchman, Coroner for Warwickshire. Inquest held 17th September, 1875:

At Long Compton on 15th September 1875, Ann TENNANT, aged 79, wife of John TENNANT, Labourer – Wilful Murder – Deliberately stabbed to death by James [Hayward] with a fork under a delusion of witchcraft. Certificate received from J. B. Couchman, Coroner for Warwickshire. Inquest held 17th September, 1875.”

The accounts of James Haywood, Ann Tennant’s assailant, indicate a man who likely had mental illness, and who was ‘excited by beer’. He lived under hard circumstances and, like many common folk of the time, sought to find a cause which would provide a solution to his troubles. Having decided that he must have been bewitched, he consulted a ‘Water Doctor’, a local cunning man called Manning (who I have studied extensively as the only practitioner of magic pertaining to the whole sorry affair). A Water Doctor specialised in deducing ailments by peering into a jar of the patient’s urine (commonly referred to as ‘water’), and evidently Manning identified a number of particles floating in Haywood’s water as the witches who were behind his unfortunate life. This would give rise to the now infamous belief that there were sixteen witches in Long Compton, sufficient to pull a wagon up nearby Meon Hill (an Iron-Age Hillfort that has long been used for witchcraft rituals – another story for another time). Embellishing the story further, and feeding his obsession, James Haywood began telling any who would listen that the village was full of witches and the retelling of the story has since led to the idea that Long Compton is home to the oldest coven in England, referenced in letters by Robert Cochrane. Contrary to popular belief, Haywood did not die in the local gaol, nor was he hanged for his crime. He continued to tell the tale, doubtless adding to the story, to visitors who came to see him in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, Berkshire, where he died of chronic abscesses and dropsy in 1890.

This account is pertinent to our enquiry as it indicates that, up to the end of the nineteenth-century at least, witchcraft was regarded as an act of malicious magic against members of the community. Indeed, ‘bewitchment’ was quite commonly the crime of which the witch was found guilty. The verb ‘bewitch’ derives from Old English and is attested in the 12th Century as biwicchen, ‘cast a spell on; enchant, subject to sorcery’.

Under the circumstances, a witch was somebody, usually female, who bewitched. Rarely, if at all, in historic records is the word witchcraft referenced in a positive connotation. That is, until the latter half of the twentieth-century, witchcraft was never regarded in the minds of peoples to be anything other than magic used to harm, or otherwise influence, the lives of others.

The Meaning of Witchcraft

Gerald Gardner may be responsible for Wicca, a modern rendition of witchcraft that incorporates elements of Thelema with the Solomonic grimoire traditions, but it was Alex Sanders who made it popular and ensured its presence in our modern world. In our occasional discussions concerning the teachings my mentor received as one of Sanders students, one thing is of particular interest: Alex didn’t teach witchcraft, he taught magic. This distinction, though seemingly subtle and quite simple, is actually of considerable consequence. Indeed, such an apparently inconsequential statement reveals in its consideration a great deal about the knowledge and understanding of Sanders. What the difference might be for him, we may only imagine. However, that he made such distinction is necessarily relevant to our discourse.

While the meaning of witchcraft has experienced a semantic shift, coming to mean divergent things to groups of people, it does still yet retain some unavoidable historic credentials. That is to say, there are some few things that we all assume are implicit in the term, however we ultimately come to identify with it. Within the greater communities, and among common parlance, these key meanings are forever embedded in terminology and idiom. These are quite separate from the purpose of the ‘Great Work’ and the systems of Theurgy which distinguish the ‘high magic’ of traditional initiatory Wicca from the Thaumaturgy with which this new and more popularist lifestyle witchcraft embraces.

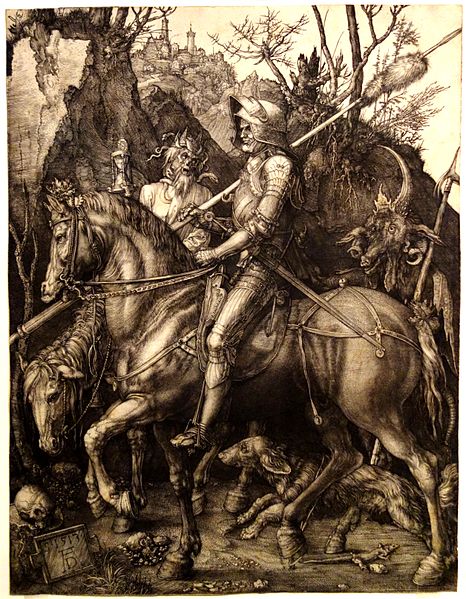

It is noteworthy that those public sodalities of Traditional Witchcraft often tend to deplore being referred to as witches. Indeed, from the avoidance of the term by Robert Cochrane, to the Nameless Arte of East Anglian heritage, we see this frequently in those traditions which observe lineaged pedigree. Once again, the distinction between witchcraft and the practices and beliefs of traditions is emphasised, whereby the term witch is avoided as carrying with it the assertion of petty, malignant and deplorable overtones. Nevertheless, how others refer to us is not always within our power, resulting in the label of witchcraft becoming attached to our certain practices or groups by proxy from outsiders. The identification of the Horsemen of East Anglia as witches for their inexplicable and seemingly miraculous power over horses is understandable, especially in a time more difficult, and less cynical, than our own and in which superstition was rife. Other examples abound, but often with those identified as using witchcraft choosing to shun the name themselves.

Taking into account those various uses and meanings of the term witchcraft, we begin to sense a common seed at the core. At its most simple level, we might infer from that thought that witchcraft implies the ability to fascinate, charm, enchant, or otherwise manipulate people or objects for our own purposes, often regarded as (rightly or wrongly) base or paltry.

There remains yet another path still, though, and esoteric witchcraft charges us to ‘keep pure your highest ideal’. Taken from the Charge of the Goddess, by Doreen Valiente, this imperative is a foundation to our philosophy and moral code, with which we may seek and aspire. This is an altogether different witchcraft indeed.

All this being said, semantic shifts occur when fertile culture allows for growth and this applies to all aspects of our world view. There can be no definitive meaning, then, and this brief foray is by no means authoritative or final. Perhaps, though, there are some few things to consider.

________

WHAT IS WITCHCRAFT? WHAT MAKES SOMETHING WITCHCRAFT? More Thoughts by Patheos Pagan Writers

What Makes it Witchcraft? by Martha Kirby Capo at The Corner Crone

What Is A Witch? Defining Witchcraft For Both Past And Present Day by Scarlet Magdalene at Tea Addicted Witch

What Makes Witchcraft . . . . Witchcraft? by Cyndi Brannen at Keeping Her Keys

Defining Witchcraft: General and Personal by Morgan Daimler at Irish-American Witchcraft

What Makes it Witchcraft? by Kelden at By Athame and Stang

On the Necessary, Ineluctable Otherness of Witchcraft by Misha Magdalene at Outside the Charmed Circle

Witchcraft Has No Gatekeepers by Jason Mankey at Raise the Horns