I’m getting back to my series of posts in which I “Get Theological” with the range of topics common in Christian systematic theology. In case you missed any, so far I’ve written about God, being human, Jesus as Christ, remember Sabbath, church, and the bible. This post focuses on the Christian claims about fundamental flaws in human nature: Sin.

I’m getting back to my series of posts in which I “Get Theological” with the range of topics common in Christian systematic theology. In case you missed any, so far I’ve written about God, being human, Jesus as Christ, remember Sabbath, church, and the bible. This post focuses on the Christian claims about fundamental flaws in human nature: Sin.

There’s a long tradition of theologians describing what sin is and where it came from, and assumptions about it by Christians throughout the generations. Those assumptions often start with the bible, in Genesis, and in the garden of Eden where supposedly sin entered the world: That the man and the woman disobeyed God, were punished, exiled, and shamed by their nakedness.

In fact, so much of what I think is wrong about sin-talk is based in that particular reading of the text, and images like the one above by the Reformation era artist Lucas Cranach.

Associating sin with disobedience makes it about God, not about how human beings live together.

Associating sin with nakedness and sex sets up millenia of destructive theological ethics around human sexuality.

Associating sin with the woman’s decision to take and eat the fruit sets up the fundamental mistrust of women that makes sexism and misogyny acceptable to this day.

Here’s what I think we need to understand about sin … it’s about us, and it’s up to us.

Sin is entirely about how human beings live together. Human beings as created by God are only and always in community with each other (in both creation stories in Genesis). And so sin is primarily about the violence and violation that we do to each other, even back when Cain killed Abel, and then it becomes about God.

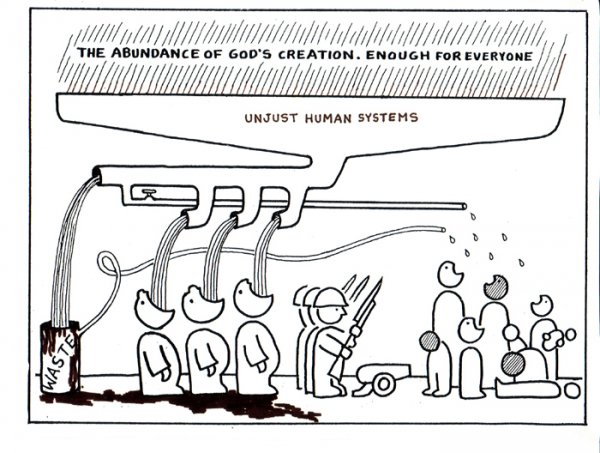

Sin is also not just about person to person violation. Because we humans, in our impressive creativity, figured out how to construct institutions and systems that govern our lives for good and for ill. These systems can be obvious and concrete, like governments and religions and educational systems. And they can be oblique and invisible, like white privilege and heterosexism and gender stratification. We have some idea of how to fix governments and religions and educational systems when they run amuck, but what about the other more oblique but just as real systems that govern our lives?

Sin is also not just about person to person violation. Because we humans, in our impressive creativity, figured out how to construct institutions and systems that govern our lives for good and for ill. These systems can be obvious and concrete, like governments and religions and educational systems. And they can be oblique and invisible, like white privilege and heterosexism and gender stratification. We have some idea of how to fix governments and religions and educational systems when they run amuck, but what about the other more oblique but just as real systems that govern our lives?

Expanding our theological conversation about sin so that it includes systemic violations done to individuals is essential if we are going to be any kind of participant in saving the human community from itself. The Christian claim that God became human in order to save humanity assumes this very point, that human beings have to participate in their own redemption. Not in the earning-it sort of way (my Lutheran soul would never allow that!), but in the accountable-for-it kind of way.

How have we been complicit in systems that depend on the destruction of others?

More importantly, what are we going to do about it?

“Adam and Eve” (1526) by Lucas Cranach image via.

“Unjust Systems” image via Dan Erlander.