In the New Testament book of James, the apostle James warns against the sin of partiality: “My brothers, show no partiality as you hold the faith in our Lord Jesus Christ” (James 2:1). He specifically calls out Christians who favor the rich and denigrate the poor, but we know that partiality wears many masks. The apostle Paul mentions a few of those masks when he says, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male or female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Paul’s point is not that we cease having race, gender, or social status when we are converted, but that the gospel makes us radically equal and we must treat everyone in the church with equal respect and dignity.

In the New Testament book of James, the apostle James warns against the sin of partiality: “My brothers, show no partiality as you hold the faith in our Lord Jesus Christ” (James 2:1). He specifically calls out Christians who favor the rich and denigrate the poor, but we know that partiality wears many masks. The apostle Paul mentions a few of those masks when he says, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male or female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Paul’s point is not that we cease having race, gender, or social status when we are converted, but that the gospel makes us radically equal and we must treat everyone in the church with equal respect and dignity.

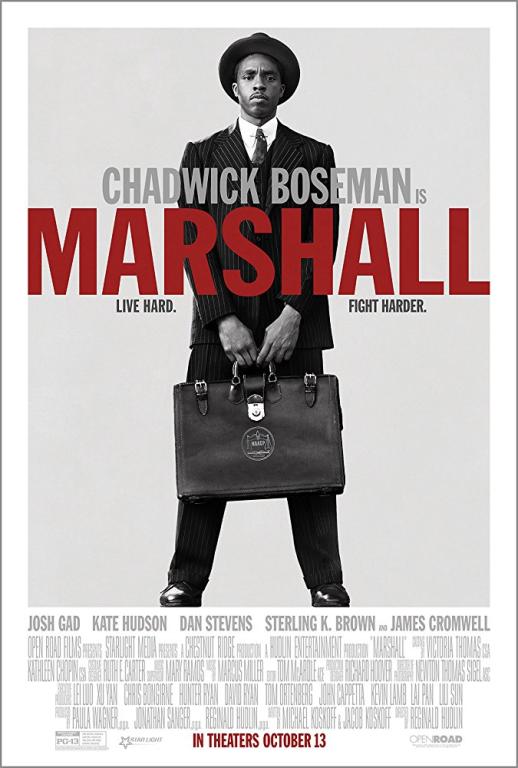

The same equality should be true in our nation’s courts, but, as many movies have shown, justice is often complicated and can be drawn down to the level of the people enforcing it. The new film Marshall, in theaters this weekend, shows us that justice is possible, but at times it takes twice the effort and danger that it should.

Chadwick Boseman, who played Jackie Robinson in 42 and James Brown in Get On Up, continues his run at the title of ‘king of biopics’ in the role of Thurgood Marshall. Marshall, of course, was the first black justice on the US Supreme Court and a towering figure in the American judicial system in the 20th century. The movie shows Marshall as a young man, the NAACP’s best lawyer, traveling to Connecticut to team up with a white, Jewish lawyer (played by Josh Gad) to defend a man named Joseph Spell (played by Sterling K. Brown) who is accused of rape and attempted murder.

I don’t know of any feature films about the life of Marshall and so I found it interesting that our first screen introduction to him is with this little-known (and morally complicated) case, rather than one of his more famous cases like Brown V. Board of Education or Murray V. Pearson. By choosing this case, however, the filmmakers help us to focus on character and universal truths rather than the specifics of a famous historical event. The fact that the case takes place in the North, rather than the standard Southern setting, and that its outcome is fairly predictable telegraph that this is more than just a legal thriller, it is first and foremost social commentary.

Marshall reminded me of two other films. The first was Race (about Jessie Owens but improbably not starring Boseman), which also compared the plight of black people in the pre-Civil Rights era with Jews in the time of Nazi Germany. The other was Mississippi Burning, which also chronicled the horrific treatment of minorities in that day, but made the massive mistake of making white FBI agents seem to be the heroes of the Civil Rights movement. Marshall is faithful to the details of Spell’s case, including the fact that the NAACP needed a white lawyer to help defend Spell and that the judge on the case ordered Thurgood to be silent throughout the trial. In contrast to Mississippi Burning, however, it is clear that it is Marshall’s intellect and strategy that allow justice to be served. This is faithful to history, as it was Marshall who traveled around the country on behalf of the NAACP, helping black defendants fight a prejudiced, seemingly rigged system by presenting superior logical arguments and outwitting white prosecutors (the book Devil in the Grove by Gilbert King is a great look at Marshall’s dangerous travels that injected hope in the black communities wherever he went).

Institutions are only as good as the people who carry out their missions. This is true in the church and it is true in the legal system. Marshall is a good reminder that we have needed, and still need, prophetic men and women to call us to a higher standard of equality and impartiality.